Walking the talk

Actions speak louder than words

“Well done is better than well said.” — Benjamin Franklin 1

How often have you seen someone profess certain beliefs and then act in ways that don’t line up with what they espouse?

Maybe you’ve even noticed yourself doing it?

If you do notice it in yourself, then you’re unusually self-aware, because most of us plough on in blissful ignorance that we’re not walking our talk.

The gap between talking the talk and walking the walk featured centrally in the collaboration between Professor Chris Argyris of Harvard and Professor Donald Schön of MIT. 2

One of the central themes of Argyris and Schön’s work was theories of action.

In the preface of their 1974 book, Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness, Argyris and Schön describe a theory of action as a cognitive program, the effective implementation of which “goes beyond knowledge of the part of the program that can be readily formulated”. 3

They further describe the challenge in learning new theories of action as arising “not so much from the inherent difficulty of the new theories as from existing theories people have that already determine practice. We called these operational theories of action theories-in-use to distinguish them from the espoused theories that are used to describe and justify behavior. We wondered whether the difficulty in learning new theories of action is related to a disposition to protect the old theories-in-use.” 4

I first encountered Argyris and Schön’s categorisation of theories of action into theories-in-use and espoused theories in an article by Argyris published in 1991 in the Harvard Business Review. 5

The categorisation of theories of action into espoused vs in-use was a helpful framing for a phenomenon I’d often seen, and still see, in organisations where someone in an influential position has read a book, attended a course, or watched a TED talk and subsequently espouses strongly held beliefs — that they don’t embody or enact.

In short, they talk the talk but don’t walk the walk.

The phenomenon is also prevalent on LinkedIn, when in promoting their “personal brand” someone espouses:

an “ethical” or “virtue based” stance — but fails to act accordingly in their responses to comments;

an openness to, or active curiosity about, other perspectives — but swiftly and summarily dismisses any that are offered;

a commitment to collective problem solving — but insists the collective problem solving is done their way;

etc.

This is because espoused theories are easy to acquire and assert, whereas in-use theories only become embraced, embodied, and embedded through actions and interactions.

The latter demands much more diligent effort, attention, and application than the simple reading and regurgitating required for the former.

An important distinction here is that whilst espoused theories are by definition explicit — otherwise we wouldn’t be able to assert them as beliefs — in-use theories are implicit or tacit.

Argyris and Schön cite the influential work of Michael Polanyi on tacit knowledge, adding to his famous dictum “We know more than we can tell” the coda “and more than our behavior consistently shows”. 6

They explain:

“If we know our theories-in-use tacitly, they exist even when we cannot state them and when we are somehow prevented from behaving according to them. When we formulate our theories-in-use, we are making explicit what we already know tacitly; we can test our explicit knowledge against our tacit knowledge just as the scientist can test his explicit hypothesis against his intimations. When we learn to put an espoused theory of action to use, we reverse the process. Instead of inferring explicit theory from the tacit knowledge our behavior shows, we make explicit theory tacit—that is, we internalize it.” 7

-

Argyris and Schön conclude: “All human beings — not only professional practitioners — need to become competent in taking action and simultaneously reflecting on this action to learn from it.” 8

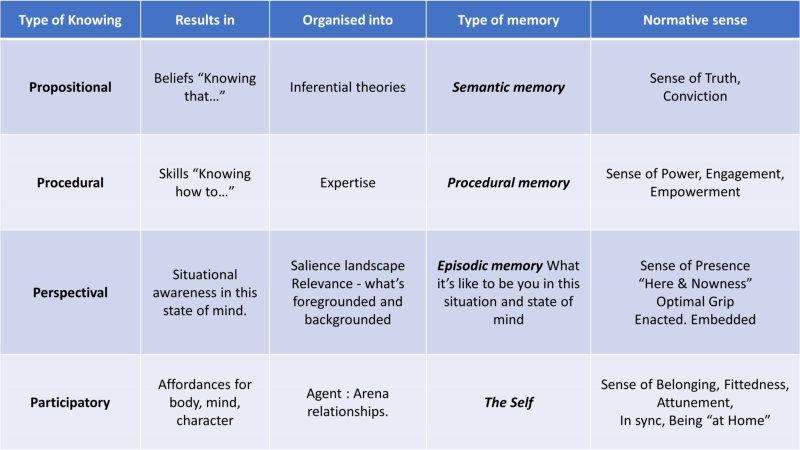

Argyris and Schön’s insights from 50 years ago mesh well with the more recent work of John Vervaeke, Professor of Cognitive Science at the University of Toronto, and a central theme in his work — that we have four ways of knowing:

1) Propositional Knowing

This is belief-centric, arising in the form of “knowing that…<insert proposition>” — for example knowing that a cat is a mammal; knowing that Paris is the capital of France, knowing that Liz Truss was UK Prime Minister for 44 days.

In propositional knowing, memory is a set of facts you believe to be true, and brings with it the normative sense of conviction.

2) Procedural Knowing

This is “knowing how” to do something — e.g. how to catch a ball, how to understand other people, how to engage in productive conversations, etc.

In procedural knowing, memory is not about facts that are true or false but about embodied skills, how apt they are, and how well they fit the context. It brings with it the normative sense of empowerment.

3) Perspectival Knowing

This is the knowing you have because you’re a conscious being with a perspective on your context. Knowing what it's like to be here right now — situational awareness — including which skills to apply, and/or you need to acquire, and to what degree.

In perspectival knowing, memory is about how things are in the foreground and background of your evolving outlook — your salience landscape — enabling you to get an optimal grip on a situation, based on your state of mind, bringing with it the normative sense of presence.

4) Participatory Knowing

This is the deepest form of knowing and the most backgrounded in your salience landscape.

In participatory knowing, memory is the curious thing we experience to be the self — bringing with it the normative sense of attunement, connectedness, co-identification, of being at home. It’s what’s lacking when you find yourself in an alien culture or context.

Vervaeke’s “4P” cognitive stack offers a very helpful framing for the distinction between Argyris and Schön’s espoused and in-use theories of action, and help point to what’s required to bridge the gap between talking the talk and walking the walk.

In essence, espoused theories of action are propositional, resulting in beliefs that engender a sense of conviction that they’re true.

In-use theories of action are, by contrast, embodied and embedded in procedural, perspectival, and ultimately rooted in participatory knowing — we feel more at home, more present, more engaged and empowered when operating from our in-use theories of action.

That’s why we’re pulled to operate from our existing theories-in-use even when we want to embody and enact different espoused theories that we believe are more apt for the future.

Hence the problem Argyris and Schön point out — “the difficulty in learning new theories of action is related to a disposition to protect the old theories-in-use”.

So, whilst we may espouse with great conviction the belief that for our organisation to thrive in an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world, sense making, decision making & action taking must become ever more tightly coupled, rapidly and repeatedly iterated, deeply embedded and widely distributed throughout the organisation, bringing such a future-fit culture to life requires displacement of old theories-in-use such as:

organisations are machines to be run efficiently — as opposed to communities of human beings co-creating value together; 9

leadership is the exclusive preserve of an elite few senior people who create a vision and then inspire, cajole, or coerce everyone else to fall into line — as opposed to the capacity of a human community to shape it’s future; 10

people work to predefined job descriptions that dictate and determine their roles based on specifications imposed by others — as opposed to organisations creating conditions where people flourish, playing to their strengths in ways that make their weaknesses irrelevant; 11

coherent organisational action is obtained by top-down command and control based on strategic planning — as opposed to iterative sense making, decision making & action taking focused on value creation and risk reduction. 12

Vervaeke points out that the greatest challenge we face is that since The Enlightenment our world has become progressively more and more obsessed with propositional knowledge.

This has led to the extreme bias in today’s world of assimilating and asserting everything from a propositional level whilst being increasingly blind to the fact that we’re not walking our talk.

Dr Iain McGilchrist makes a similar critique, framing it in terms of the post-Enlightenment dominance of left hemisphere ways of attending to the world via schema, maps, and models, whereas the right hemisphere presences reality in much richer, more meaningful ways that reflect Vervaeke’s deeper levels of procedural, perspectival, and participatory knowing.13

We urgently need a New Enlightenment where we individually and collectively take responsibility for rehabilitating, reenergising, and reclaiming these deeper levels of knowing — in our organisations in particular and our lives in general.

Questions for reflection

How much time and attention do I spend on assimilating more propositional knowledge through books, courses, videos etc — compared to the time and attention I spend on developing new procedural skills, situational awareness and being at home with creating and inhabiting a future-fit culture?

What in-use theories of action do I currently embody and enact? When push comes to shove, what behaviours emerge that reveal outdated legacy theories-in-use?

How much attention do I pay to my intentions and motivations so I can see when and where I need to take corrective action to more consistently walk my talk?

What am I doing to achieve greater alignment between what I espouse and what I embody in my day to day actions and interactions?

Argyris and Schön published several books together in the field of education and organisational learning including: Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness (1974) Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective (1978) and Organizational learning II: Theory, method and practice (1996).

Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness on Goodreads

Ibid Theory in Practice Preface page viii

Teaching Smart People How to Learn by Chris Argyris, HBR May-June 1991 p99-109

This previous post provides an introduction to Polanyi’s work.

Ibid Theory in Practice p11. By “formulate our theories-in-use” Argyris and Schön are referring to efforts to make our tacit knowledge explicit by paying close attention to the motivations and intentions behind our attitudes and behaviour to gain insight into the underlying theories-in-use.

Ibid Theory in Practice p3

I describe some of the metaphors by which we understand organisations on pages 17-21 of my 22 page report The Five Fatal Habits into why organisations have consistently failed to create future-fit cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness over the past 30 years. Free download here.

I explore this theme further in an earlier piece Leadership not Leaders.

This was a consistent theme in the work of the legendary Peter Drucker as described in the Five Fatal Habits (Ibid) pages 12-13.

See the earlier article From Strategy to Sense Making.