From Strategy to Sense Making

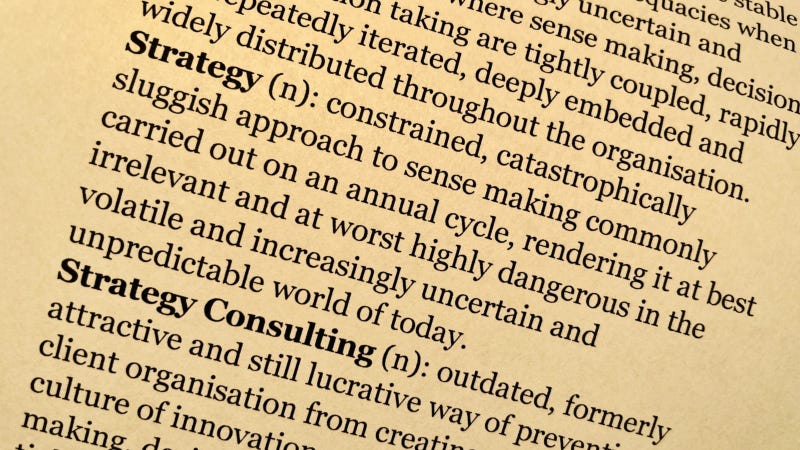

'Strategy' used to be the sine qua non of top management. But in an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world, it's a catastrophically sluggish, constraining approach to sense making.

“Everyone has a game plan until they get punched in the face.” — Mike Tyson 1

Much has been said and written about how Nokia missed the smartphone revolution despite their supposed strategy of “Connecting People”. 2

And how Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer laughed at the iPhone in 2007, then in a ‘strategic’ scramble, bought the rump of Nokia's handset business for $7.2Bn in 2013 - an investment that dramatically missed the market, and was ditched two years later in a $7.6Bn write-off. 3

Alex Rampell of leading Silicon Valley Venture Capital firm Andreessen Horowitz (approx $20Bn in assets under management) described the challenge facing senior executives like Ballmer: 4

"The battle between every startup and incumbent comes down to whether the startup gets distribution before the incumbent gets innovation".

You can bet that challenge is animating minds at Mercedes, Audi and BMW as they witness the rise of Tesla, Uber (pandemic notwithstanding) and Waymo. 5

Similar revisiting of ‘strategy’ is no doubt exercising little grey cells at Amex, Visa and Mastercard as market share goes to Paypal, Stripe and Ant. 6

Decades ago, the default course of action when facing new competitors was to bring in a consulting firm like McKinsey, BCG, or Bain to help devise a new strategy.

But in an increasing uncertain and unpredictable world, strategy falls foul of ‘The Grand Fallacy’ identified by Professor Henry Mintzberg in the mid-1990’s 7:

“No amount of elaboration will ever enable formal procedures to forecast discontinuities, to inform managers who are detached from their operations, to create novel strategies.

Ultimately, the term ‘strategic planning’ has proved to be an oxymoron”.

In a world of increasingly disruptive discontinuities, what should senior executives be doing instead?

To answer that question, it's useful to unpack how strategy became so central to senior executive thinking.

Organisational strategy first became a hot topic in the 1960’s, as a way for top management to make sense of the world and decide where, and where not, to focus. 8

The world was much more stable and predictable back then, so the idea was you produced a new strategy every few years, distilled it into plans, and 'cascaded' it down through the management layers.

But as the pace of change increased, strategies had to be updated ever more frequently, in response to new technologies, competitors, societal trends, etc.

That’s when strategy consulting really took off, bolstering the inevitably limited capacity of the senior executives to handle the increasing pace of change.

The practice continues to this day, feeding a $36bn strategy consulting industry. 9

Some organisations recognised the fundamental limitations and significant risks of relying on single strategies that depended on predicting an increasingly uncertain future.

Royal Dutch Shell pioneered an approach known as Scenario Planning as far back as 1968 to identify a range of possible futures that might unfold, based on changing contextual drivers, including social, technological, economic, environmental, political, and prevailing values. 10

The first scenarios were ready by 1972, including one based on an oil price of $8 per barrel. Shell managers found this scenario inconceivable - oil prices had only ever been between $2.50 and $3.50 for 25 years. 11

Then came the 1973 oil crisis, and by March 1974, the price hit $10 per barrel. 12

Having at least considered the ‘inconceivable’ $8 scenario meant Shell fared much better than other oil majors in the crisis. But afterwards, its managers still tended to revert to their strategic planning habits of the past.

My former colleague Arie de Geus took over Shell’s Group Planning function in 1982 and saw that, despite the salutary lesson of the oil crisis almost a decade earlier, top management had still not institutionalised the linkage between scenarios developed and decisions made. 13

He realised that this was largely because people were not involved sufficiently in creating the scenarios and so couldn’t relate to them as credible possible futures. 14

This led to Arie’s groundbreaking 1997 HBR article “Planning as Learning”, his book “The Living Company” and his lifelong interest in organisational learning — a term he introduced to our mutual colleague Dr Peter Senge.

Since then, the pace, scale and unpredictability of change has continued to accelerate.

Twenty years ago, senior executives still had time to make considered, data-driven decisions, explore and extrapolate trends in technology, politics, environment, economics, and societal values.

They had time to interpret the past actions and infer future intentions of current competitors and potential new entrants, formulate strategies and devise operating plans, cascade them down the organisation for execution.

They had time to hire management consulting firms to help create strategies by:

Providing insights into market and technology trends - which, unlike today, were not then widely available from multiple online sources.

Interviewing people in the body of the client organisation to tap into their sense making - hence the caricature of a management consultant as “someone who steals your watch and then tells you the time”.

But as technology-driven disruption, globalisation, and demographic shifts fuelled the pace, complexity, and unpredictability of change, the time available for each strategic planning cycle got shorter, and shorter.

Eventually it crossed the threshold where, by the time strategies were formulated and plans rolled out, the world had moved on, rendering the strategies and plans obsolete.

The reason consultants acquired the above caricature is that they know full well that the best sense making occurs in the body of the organisation, where people are:

in ongoing, direct contact with customers and therefore best placed to pick up early signals of emerging customer trends

actively involved in day-to-day value creation and therefore best placed to see what’s working, what isn’t, and identify potential improvements

from a wide range of social backgrounds, generational cohorts, and life experiences, providing much richer diversity of perspectives

That’s why, in an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world, long-term survival depends on creating a culture where sense making, decision making & action taking are ever more tightly coupled, rapidly and repeatedly iterated, deeply embedded and widely distributed throughout the organisation.

Only such a future-fit culture can cope with, and create benefit from, the unpredictable discontinuities that all organisations must increasingly face.

When senior executives only tap into this sense making once or twice a year to formulate strategy, they only ever capture a narrow, limited, static snapshot of its dynamically evolving richness.

As a result, the traditional organisational strategy has become a massively constrained, catastrophically sluggish way to steer an organisation.

By March 2020, Covid-19 had blown strategic plans out of the water, underlining the utter futility, and potential fatality, of what Mintzberg had foreseen a quarter century ago - the fundamental inability of strategic planning to forecast discontinuities.

The pandemic has made the inadequacies of strategic planning abundantly clear to everyone, except the strategy consultants themselves because, as Upton Sinclair famously noted, “It’s difficult to get someone to understand something, when their salary depends on them not understanding it.” 15

Following the pandemic, organisations are increasingly becoming aware that their long-term survival depends on creating an adaptive culture of innovation and agility that can not only cope with, but actively benefit from, the unpredictable discontinuities that we must now increasingly face.

The historical reliance on strategy consulting to help senior executives in their decision making has, for far too long, prevented them from dynamically harnessing, learning from, and improving the sense making already going on in the body of their own organisations.

This has created a damaging legacy of devalued, demotivated and disengaged people in most organisations - the very people on which future organisational success depends.

As Alex Rampell described above, whether incumbent organisations manage to turn this around will decide their fate in their future battles with startups, scaleups and new entrants hungrily eyeing up their breakfast, lunch and dinner.

The key question now is whether, post-pandemic, these organisations will backslide into old habits that smother, stifle and strangle the emergence of the innovation and agility on which their futures depend.

Big consulting firms will continue to entice them to regress, but will senior executives resist their allure, and find the resolve to mobilise their own people to create future-fit cultures instead..?

It’s often debated whether Tyson or his coach Cus D’Amato said this first. Here’s Iron Mike saying it...

For example, this piece from INSEAD business school.

Financial Times: “Microsoft takes $7.6bn Nokia writedown and cuts 7,800 jobs"

Andreesen Horowitz post from 5 November 2015

In October 2020, Ant Group was set to IPO at over $300bn until the Chinese Government intervened and, in April 2021, absorbed Ant into China's state-controlled central bank.

Strategy Consulting is usually attributed to Bruce Henderson, who left Arthur D. Little to found Boston Consulting Group (BCG) in 1963 and invented the famous Boston Matrix with which BCG dominated strategy consulting throughout the 1970’s.

In 2018, strategy consulting was a $30.9bn industry with a CAGR of 5.24%.

Scenarios are formed by looking at which of these ‘STEEPV’ drivers are trending in more or less predictable ways and then creating a range of future scenarios that take these into account alongside variations in how the less predictable drivers might play out.

A barrel of West Texas Intermediate (WTI or NYMEX) crude was $2.57 in 1948 and $3.56 in 1972.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1973_oil_crisis

Arie and I served together on the boards of the Society for Organisational Learning (UK) from 2009-2015 and Lord David Owen’s anti-hubris charity The Daedalus Trust from 2010-2017.

Sinclair was 1934 Democratic nominee for Governor of California and a prolific author of almost 100 books. He often used variations of this quote, e.g. in “I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked” (1935), ISBN 0-520-08198-6; reprinted by University of California Press, 1994, p. 109