The Seeing-Being Trap

What happens when we identify too closely with our inevitably narrow, biased, and one-sided perspectives...

“Everyone takes the limits of their own field of vision to be the limits of the world”. — Arthur Schopenhauer 1

Several years ago I read the frustratingly unsatisfying book “The Knowing-Doing Gap” (2000) subtitled “How Smart Companies Turn Knowledge into Action” by Stanford professors Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert Sutton. 2

Why frustratingly unsatisfying?

Simply because it failed to do what it promised. The subtitle misled the reader to believe they’d reveal “how smart companies turn knowledge into action”. But the authors did no such thing — confessing instead that: “We found no simple answers to the knowing-doing dilemma”.

They then sought to justify this failure by claiming “Given the importance of the knowing-doing problem, if such simple answers existed, they would already have been widely implemented.” 3

Define irony — a book claims to illuminate the gap between knowing and doing but concludes that if we knew why the gap existed we’d have done something about it.

So why does the knowing-doing problem persist, and why did Pfeffer and Sutton singularly fail to discover the answer? 4

Like many academics, and the people they influence, the authors mistakenly equate “knowing” and “thinking”.

This was something pointed out in inimitably insightful style by the late Sir Ken Robinson in his famous TED talk Do schools kill creativity? (viewed 76 million times).

“If you were to visit education as an alien and say "What's it for, public education?" I think you'd have to conclude, if you look at the output, who really succeeds by this, who does everything they should, who gets all the brownie points, who are the winners -- I think you'd have to conclude the whole purpose of public education throughout the world is to produce university professors. Isn't it? They're the people who come out the top. And I used to be one, so there.

“And I like university professors, but, you know, we shouldn't hold them up as the high-water mark of all human achievement. They're just a form of life. Another form of life. But they're rather curious. And I say this out of affection for them: there's something curious about professors. In my experience — not all of them, but typically — they live in their heads. They live up there and slightly to one side. They're disembodied, you know, in a kind of literal way. They look upon their body as a form of transport for their heads. It’s a way of getting their heads to meetings…” 5

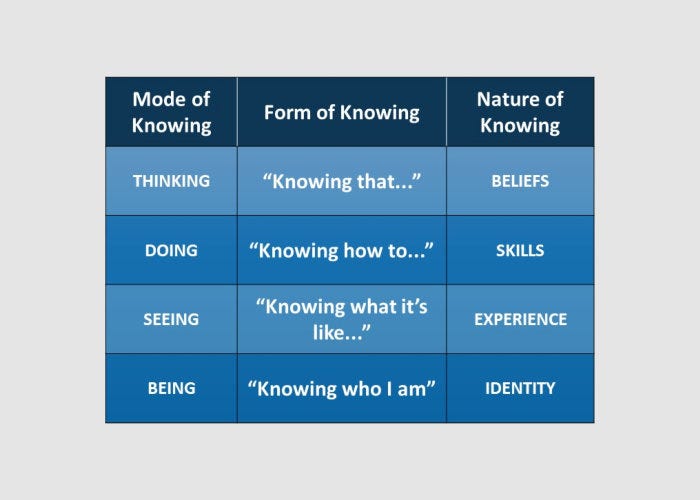

What Sir Ken is obliquely referencing is the fact that knowing goes much deeper than just the “disembodied head” level of thinking at which we form beliefs.

Knowing includes the deeper, more embodied doing level at which we know in the form of skills.

It includes the even deeper, even more embodied seeing level where we know in the form of our experience.

And it ultimately includes the deepest embodied being level where we know our selves and others in terms of the identities we adopt and assign.6

The mistake “book smart” people such as academics typically make is to overly focus on the surface thinking level and ignore the three deeper layers — even though these deeper layers are always active.

Even when individuals overly focus on knowing as thinking, they still develop skills at the doing level — e.g. skills in thinking, reasoning, logical argumentation, writing academic papers, getting papers published, giving lectures etc.

And they still accumulate experiences at the seeing level — e.g. experience of having papers accepted or rejected by journals, being cited or not being cited by others, gaining or failing to gain tenure etc.

These then cultivate an identity of being an expert, clever, knowledgeable, someone others should listen to, etc.

As Sir Ken points out, not all academics fall into this trap, and I’m fortunate enough to know several who do a good job of avoiding it.

The identification of the deepest level of self with the surface level of thinking is ultimately a problem we all face to some degree.

And when we fall into the trap of identifying our self with our inevitably narrow, biased, and one-sided perspectives we can no longer extend our field of vision beyond the limits of what we already see.

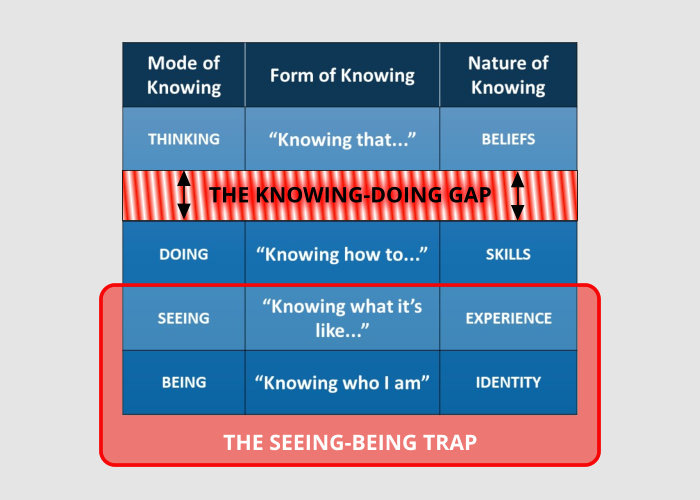

This is the reason for the effect Schopenhauer describes in the quote at the beginning of this article — our seeing gets coloured, biased and constrained by our being, and by mistaking the limits of our field of vision for the limits of the world, we’re caught in a seeing-being trap.

In fact the knowing-doing gap cited by Pfeffer and Sutton is actually a misnomer — it’s really the thinking-doing gap.

And the reason for the thinking-doing gap is the deeper influence of the seeing-being trap.

There are all sorts of seeing-being traps any of us can fall into:

‘I am clever’

‘I am special’

‘I am the founder’

‘I am the owner’

‘I am the boss’

‘I am the founder, owner or boss’s chosen protégé, relative, apprentice etc.

etc, etc, etc

Working with a colleague who’s caught in a seeing-being trap can be irritating, exasperating, or infuriating.

But when key influencers get caught in seeing-being traps, organisational efforts to cultivate future-fit cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness weaken, wither, and ultimately die. 7

The three most common seeing-being traps affecting key influencers I’ve encountered over the past 35 years across cultures throughout the world are: ‘I am the expert’, ‘I am the decision-maker’ and ‘I am the resource controller’.

“Experts”

The first common seeing-being trap — ‘I am the expert’ — often affects those with specialist industry, market, customer or technology knowledge.

When it does, they miss, or dismiss, the new innovations, insights and ideas that will ultimately render their expertise obsolete.

In the awareness of being “the expert”, other perspectives will look self-evidently wrong and — as the self-perceived expert — I’ll expect others to accept my perspective as more valid than anyone else’s, including their own.

The chances of them doing that are of course close to zero — because what they’ve done, experienced, and the sense of self they’ve developed are vastly more real to them than your claimed expertise.

“Decision Makers”

The second common seeing-being trap — ‘I am the decision-maker’ — often affects senior executives, particularly ones who’ve worked in the traditional top-down command & control hierarchies of the past.

Someone caught in this trap will feel “I have to make the decisions”, which makes them a decision-making bottleneck for the organisation.

This results in poor decisions due to the inevitable limits of their capacity and bandwidth, made worse by the stress of their constant self-imposed overload.

Senior executives are of course ultimately responsible and accountable for the decisions that determine their organisations’ results.

But there’s a world of difference between the attitudes, behaviours, actions and interactions that stem from the mindset: “I have to make the decisions” and the much more future-fit mindset: “I have to ensure good decisions get made and implemented”.

The latter mindset allows others to contribute their knowledge, insights, wisdom and experience to decision making.

And, since none of us is as smart as all of us, this invariably leads to better decisions.

Not only that, but by being involved in the process others are much more able, inclined and inspired to implement the decisions in practice.

And, what’s more, because they understand the thinking behind the decisions, they’re much better placed to make the kind of innovative, agile, adaptive adjustments that are almost always required when the rubber meets the road.

“Resource Controllers”

The third common seeing-being trap — ‘I am the resource controller’ — often afflicts those who wield delegated power to grant or deny access to resources such as funding, manpower, equipment and facilities.

This includes those with ‘sign-off’ authority in Accounting, HR, Legal and other compliance-related functions.

Resource controllers tend to be isolated and insulated from the day to day reality experienced by colleagues ‘at the coalface’.

This gets worse when organisations institutionalise the separation with outsourcing or ‘shared services’ arrangements.

The physical and psychological distance this creates leads to arms-length control and monitoring that unintentionally but almost always makes it harder to get things done.

People are then forced to resort to what they see as ‘workarounds’ and resource controllers see as ‘non-compliance’.

This sets up a vicious cycle in which increasingly restrictive rules lead to ever more work arounds, resulting in an exponential increase in the misunderstandings and mistrust that undermine innovation and agility.

The negative effects of key influencers stuck in seeing-being traps like these are systemic and far-reaching.

Key influencers mistaking the limits of their field of vision to be the limits of the world are the root cause reason so many high-profile market-leading firms forfeit their future to disruptive innovators.

Like Nokia did to Apple and Android smartphones, Blockbuster to Netflix and Toys R Us to online retailers like Amazon.

So how can we help ourselves and others to avoid or escape seeing-being traps?

The secret lies in cultivating the awareness that no matter how important a role I may be currently playing, it is just that — a role I’m playing, not who I am.

The distinction sounds subtle, but its implications are immense.

That’s because any role we play can become less important and even, ultimately, cease to exist.

If we mistake our roles for ourselves, then any threat to the role feels like a threat to our personal survival.

Quite understandably, this triggers strong psychological defence mechanisms including denial, blame and justification.

These invoke powerful emotional states that make our existing narrow, biased, and one-sided perspectives feel even more real, so they become further entrenched.

The power with which seeing-being traps maintain hold of their victims makes them the number one personal barrier to the creation of future-fit cultures.

And when they affect key influencers, the systemic knock effect is to block the wider adoption of future-fit mindsets, attitudes, and behaviours.

The net result is to firmly anchor the organisation in past orthodoxies, and to stifle, smother and strangle the innovation, agility, and adaptiveness on which its future depends.

Questions for reflection

Which seeing-being traps are most problematic in your organisation..?

Which traps are you most susceptible to falling into personally..?

Where is your greatest tendency to identify role with self?

What are you doing to help yourself and others escape these traps — and to avoid falling into them in future..? 8

Schopenhauer published a collection of thoughts in Parerga and Paralipomena - Greek for Appendices and Omissions - in 1851. These were subsequently published in various English collections including Studies in Pessimism, translated by Thomas Bailey Saunders in 1913. Within Studies in Pessimism a section titled Further Psychological Observations includes this full quote [Item 69]: “Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world. This is an error of the intellect as inevitable as that error of the eye which lets us fancy that on the horizon heaven and earth meet. This explains many things, and among them the fact that everyone measures us with his own standard—generally about as long as a tailor's tape, and we have to put up with it: as also that no one will allow us to be taller than himself—a supposition which is once for all taken for granted.”

Ibid Knowing-Doing Gap p5.

In essence, the “gap” of the book’s title reflects the fact that executives mostly know what they need to do to create better organisations, but don’t do what they know.

Sir Ken Robinson’s TED talk “Do schools kill creativity?” is viewable on the TED website here. The quote section is from 09:15 to 10:25.

Some of the more philosophically minded, especially those familiar with Eastern schools of thought, will claim that beneath the being level is another still deeper level — pure being, or universal consciousness, or some equally esoteric label. However, in real-world organisations a four-layer model works just fine.

When you understand an organisation’s culture as “the system of mindsets forming and informing people’s awareness of the way we do things round here” you can identify patterns of influence that inevitably lead back to a small number of individuals. It is these key influencers — not always in the most senior positions — whose mindsets, attitudes, and behaviours systemically affect the mindsets, attitudes and behaviours of everyone else. For more detail see the previous article: “Focus on key influencers”.

For more details on how to do this, see this previous article “Escape the trap”.