“In essence, organizational transformation is the creation of a new organizational reality. As such, it requires changing not only the practices, policies, behaviours, and structures but also the underlying mental models, meanings, and consciousness of the people involved.” — Joan Lancourt 1

Three decades ago, my former colleague Joan Lancourt and her MIT Sloan colleagues Ed Nevis and Helen Vassallo conducted extensive research into organisational transformation, publishing the results in their 1996 book Intentional Revolutions. 2

The research identified seven channels through which people in organisations pick up the clues, cues, signs, and signals to infer “the way we do things round here”. 3

They concluded that an organisation’s culture emerges, is sustained and/or changed based on the often subtle messages people receive through these channels, which they labelled:

Persuasive communication

Participation

Role modelling

Expectancy

Structural Rearrangement

Extrinsic Rewards

Coercion

When you explore what people in various parts of the organisation pick up through these seven channels, you’re able to uncover patterns of influence that inevitably lead back to a small number of individuals.

It is these key influencers whose mindsets, attitudes, and behaviours systemically affect the mindsets, attitudes and behaviours of everyone else.

This makes key influencers the highest leverage place to change the system of mindsets that forms an informs people’s awareness of the way we do things round here — in other words, the culture. 4

The pattern of key influencers in every organisation is different, and contrary to what’s often assumed, the key influencers are not always in the most senior positions.

What makes a person a key influencer is not their position in the formal organisational structure, it’s their social influence — i.e. what they do and how they do it has a significant systemic effect on the mindsets, attitudes, and behaviours of many other individuals.

The fact that the key influencers aren’t always in the most senior positions often gets overlooked, and this is one of the main reasons efforts to create future-fit cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness so frequently fail.

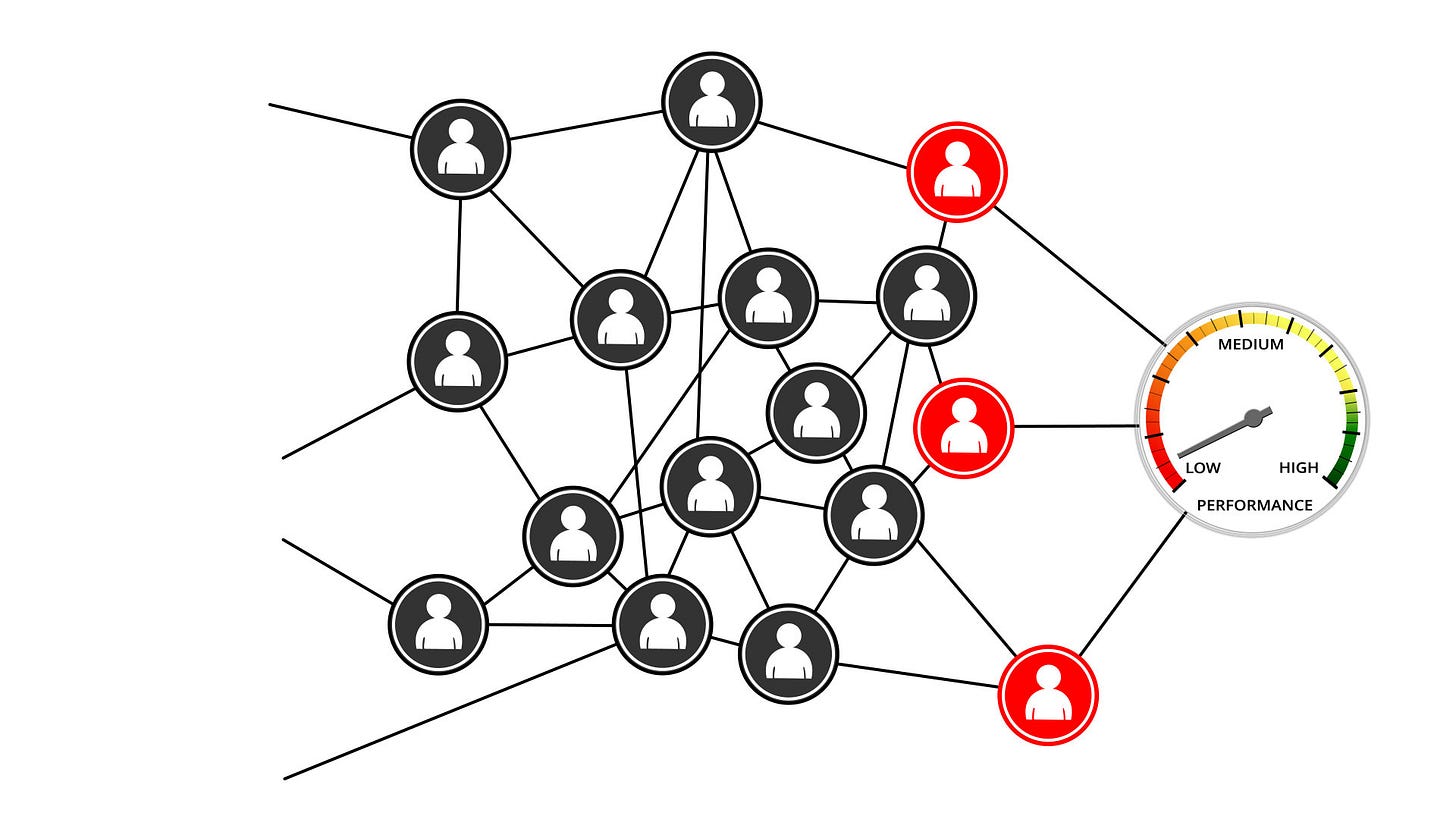

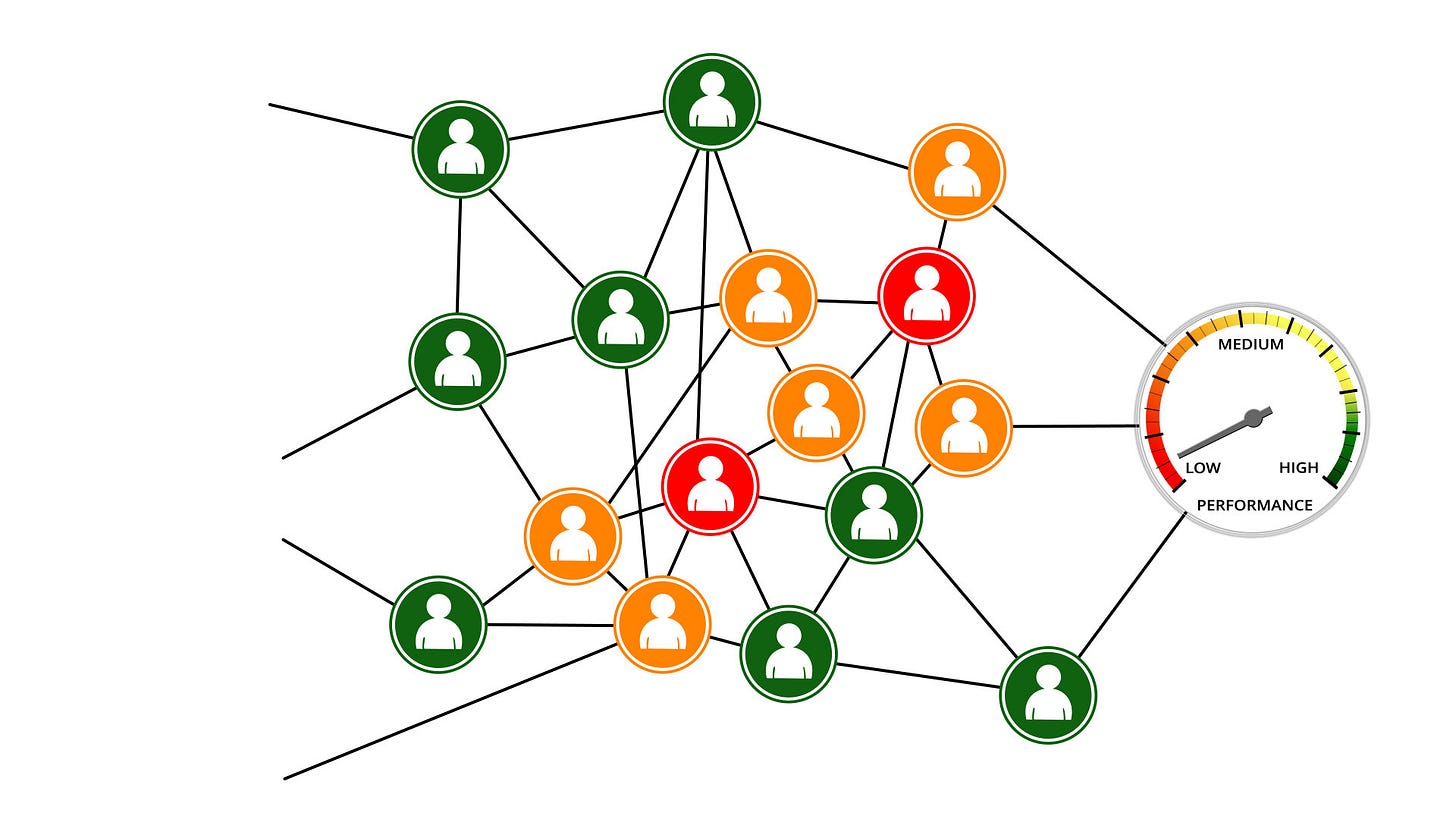

Figure 1 below represents part of an underperforming organisation, with the people most visibly involved in delivering observed results shown in red.

On the surface, these people appear to be the ones who need to “lift their game”.

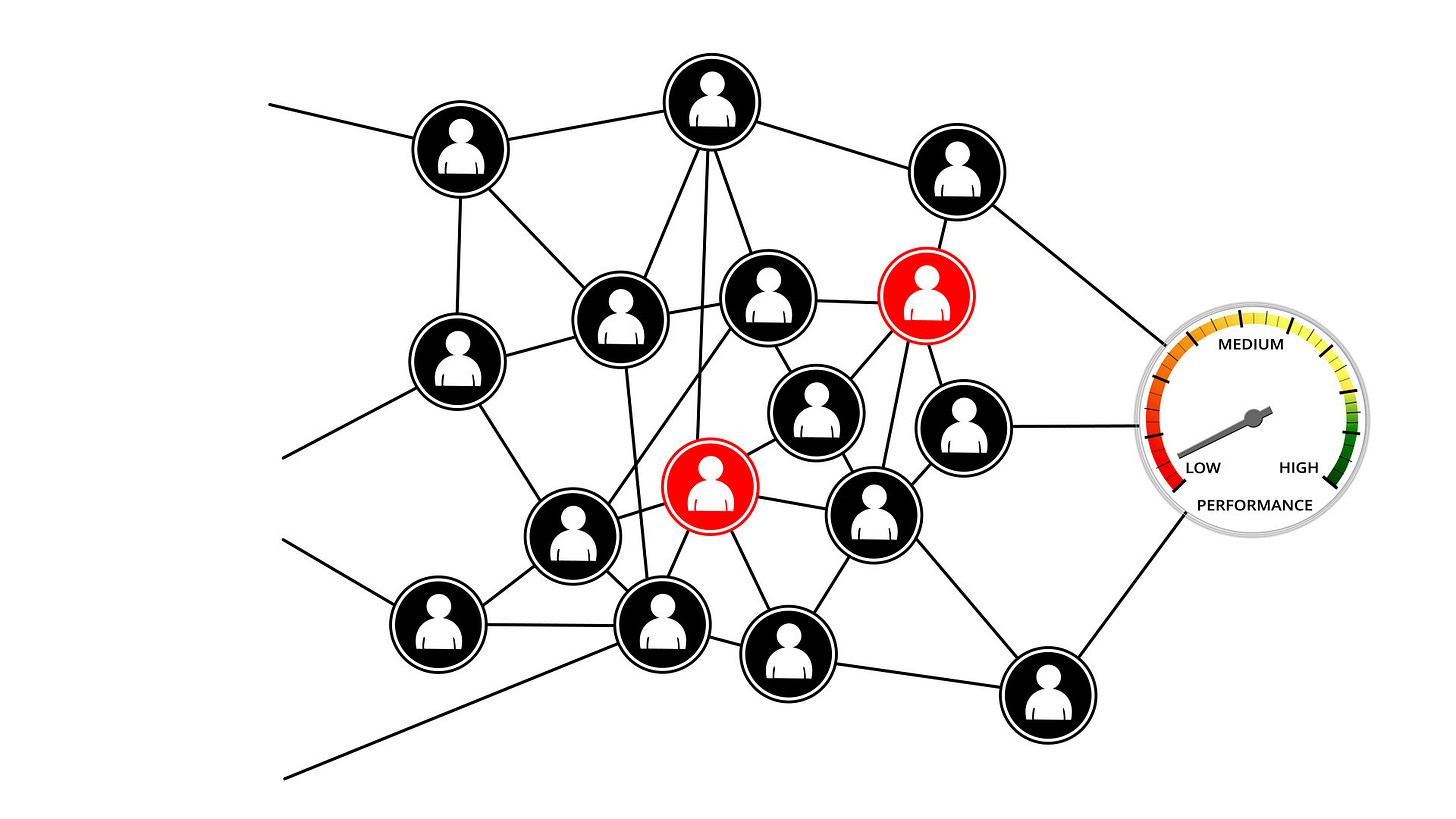

Figure 2 below shows the same part of the organisational network, but this time with the actual key influencers highlighted in red.

The behaviour of these key influencers has a systemic knock-on effect on various other individuals, shown in orange in Figure 3 below, and this is what leads to the low performance.

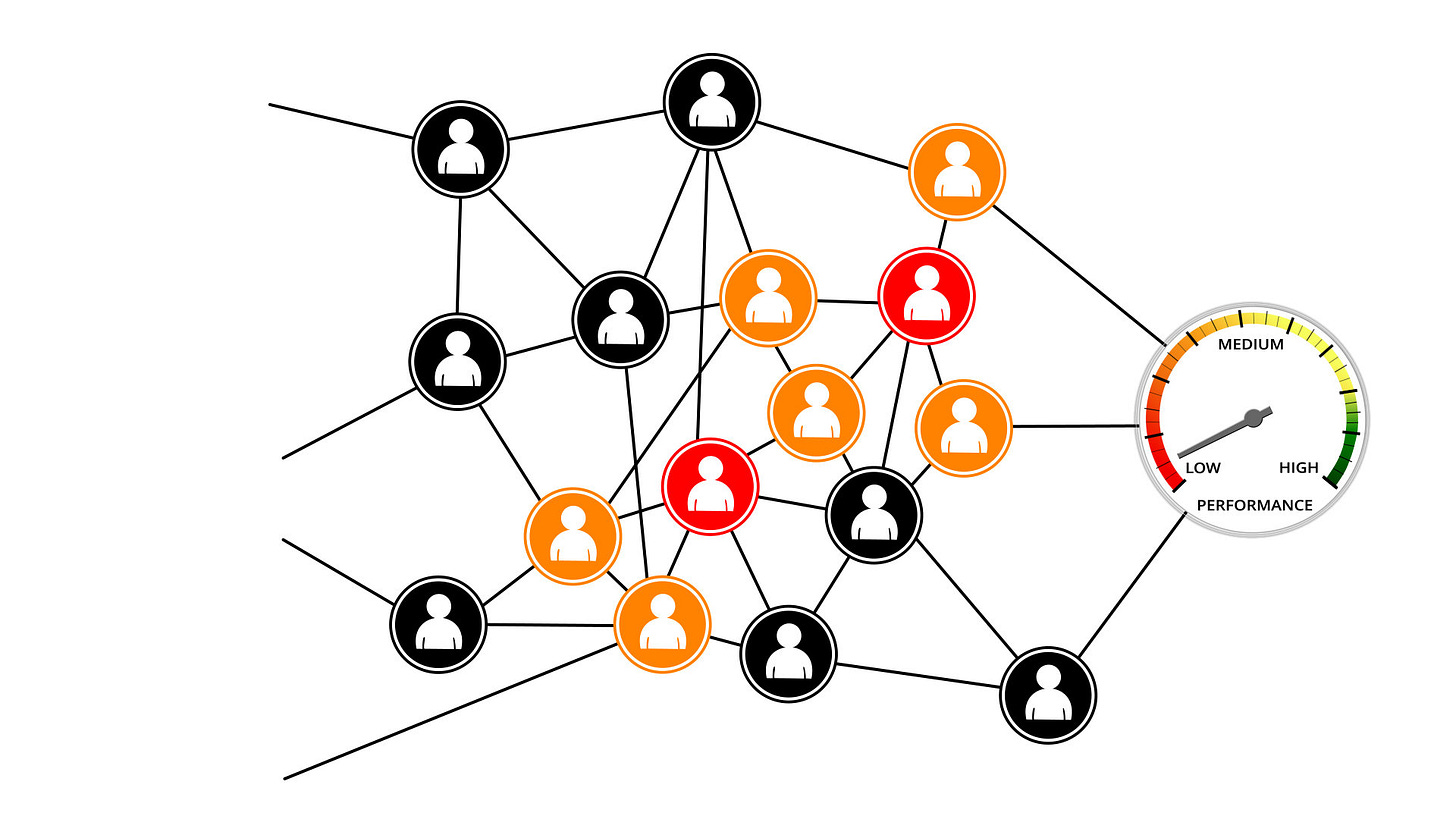

Notice how, despite this negative influence on the “oranges”, there are still a number of people, shown in green in Figure 4 below, who remain unaffected.

So, how do you find the actual key influencers so you can begin to understand, and help them shift their mindsets — and therefore the attitudes and behaviours that drive the culture and performance?

A good place to start is by exploring the perspectives of various individuals in and around the areas where the culture seems most bogged down in legacy habits of the past, and failing to become fit for an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable future.

Triangulating between these various perspectives, particularly the different ways things look to those most affected — the “oranges”, and those seemingly unaffected — the “greens”, leads to insights regarding the messages people are receiving via the seven channels.

These insights help you to form a picture of the system of mindsets creating the current culture, leading you back to the key influencers whose mindsets systemically dictate wider perceptions of “the way we do things round here”. 5

The best way to approach shifting key influencer mindsets depends on various factors, including which of them seems most pivotal, who seems most entrenched in their current 2D perspectives, and who seems most interested, inclined or inspired to shift from “red” to “green” by adopting a 2D3D innovative mindset instead. 6

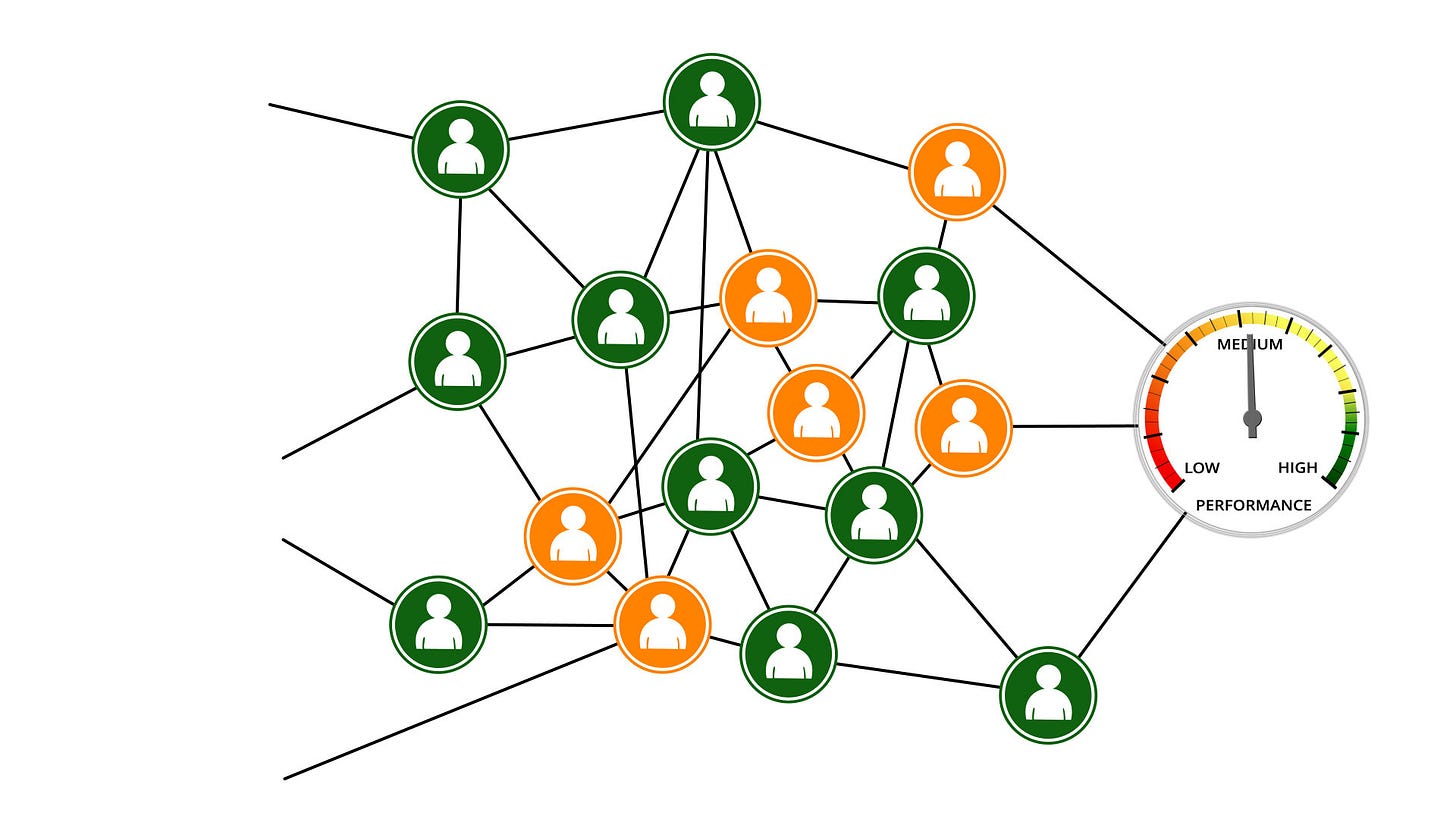

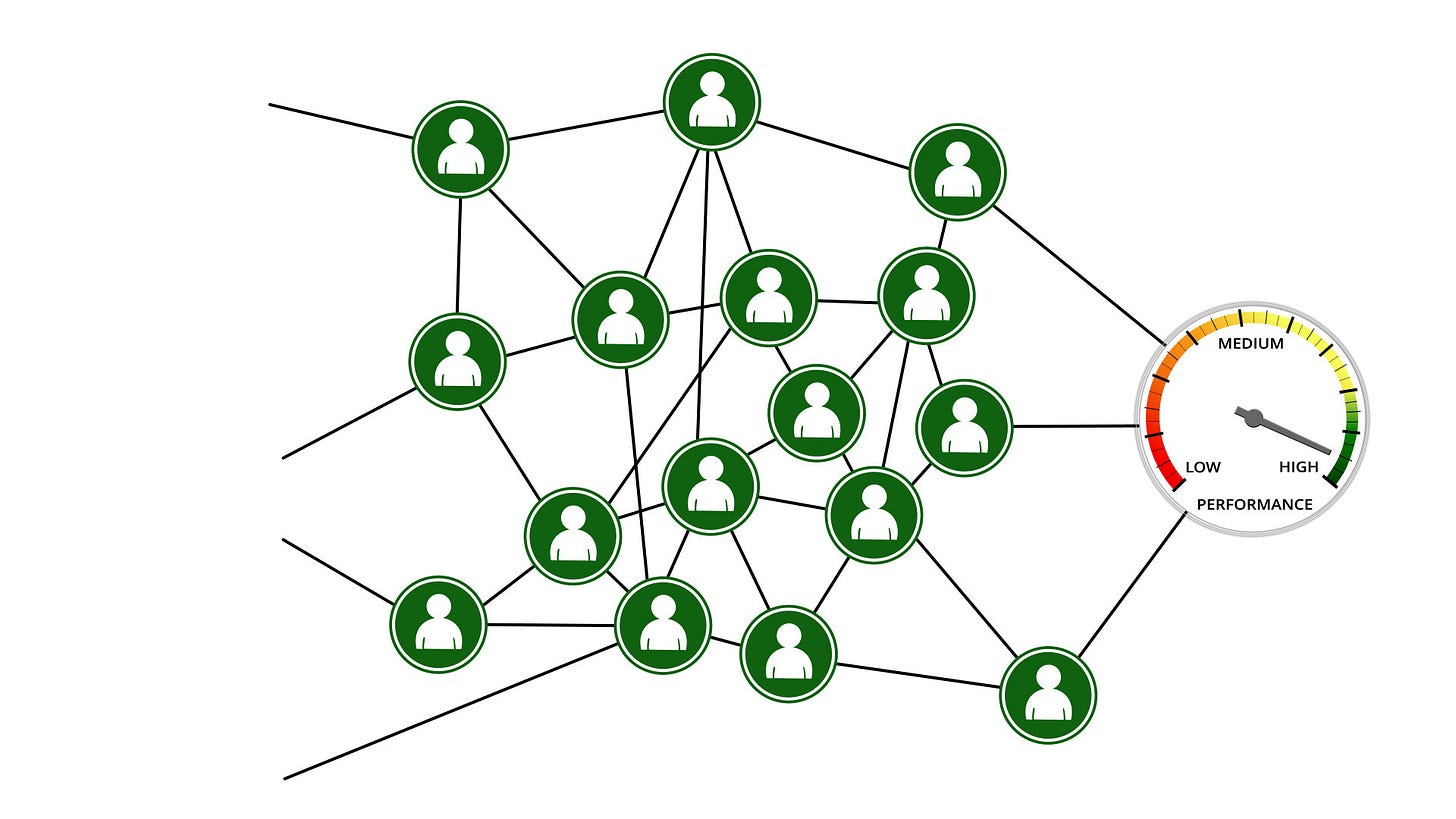

When key influencers make the shift from red to green, as shown in Figure 5 below, it begins to release the logjam around them, noticeably lifting performance.

As the shift in key influencer mindsets then ripples through the remaining “oranges”, these become “greens”, progressively unleashing greater performance, as shown in Figure 6 below.

Client example

Here's a specific client example to illustrate the approach in action.

It's from about twenty five years ago, and it had a major impact on my work ever since.

The recently-hired CEO of a biotech company called me in after things ground to a halt following his announcement that “From now on, this organisation will be market driven”.

Since the business had always been technology driven, this immediately disengaged people on the Technology side of the business, who heard the CEOs message as “Marketing are now calling the shots”.

What Marketing heard was “We have full control of the strategy, at long last”.

When I got involved, Technology and Marketing had been hunkered down in their respective bunkered silos for several months, lobbing rocks, hand grenades, and the occasional cruise missile at each other.

When there are conflicts between fiefdoms, factions and silos like this, breaking the deadlock invariably involves getting key influencers on either side of the divide to recognise that although the problem appears to be the fault of the other party, the underlying reason is a conflict between different 2D perspectives — none of which is ever the whole picture. 7

Once the different factions see how each of their 2D perspectives makes perfect sense taken in isolation, but together create the deadlock, it creates conditions conducive to the emergence of 2D3D mindsets. 8

This opens up the capacity for colleagues on either side of the erstwhile divide to engage more productively with each other and move the organisation forward together.

In this case, the breakthrough occurred when key influencers saw that Technology and Marketing’s separate 2D takes on “being market driven” had prevented everyone from seeing the bigger picture that, in fact, they needed to drive the market.

The reason this experience had such a major impact on my work with clients ever since is that, despite received wisdom to the contrary, it proved that culture change doesn’t have to be a risky, tortuous, long, drawn-out, and painfully expensive process.

It was amazing to see how shifting a few key influencer mindsets transformed attitudes and behaviours in the Technology and Marketing functions literally overnight, enabling them go on to build a successful multi-million dollar business together.

When I revisited them a few months later, the SVP of Marketing told me: “Until you arrived, it felt like we were driving round and round a roundabout — and when we asked the CEO which road he wanted us to take he would just shout back “drive faster...!”.

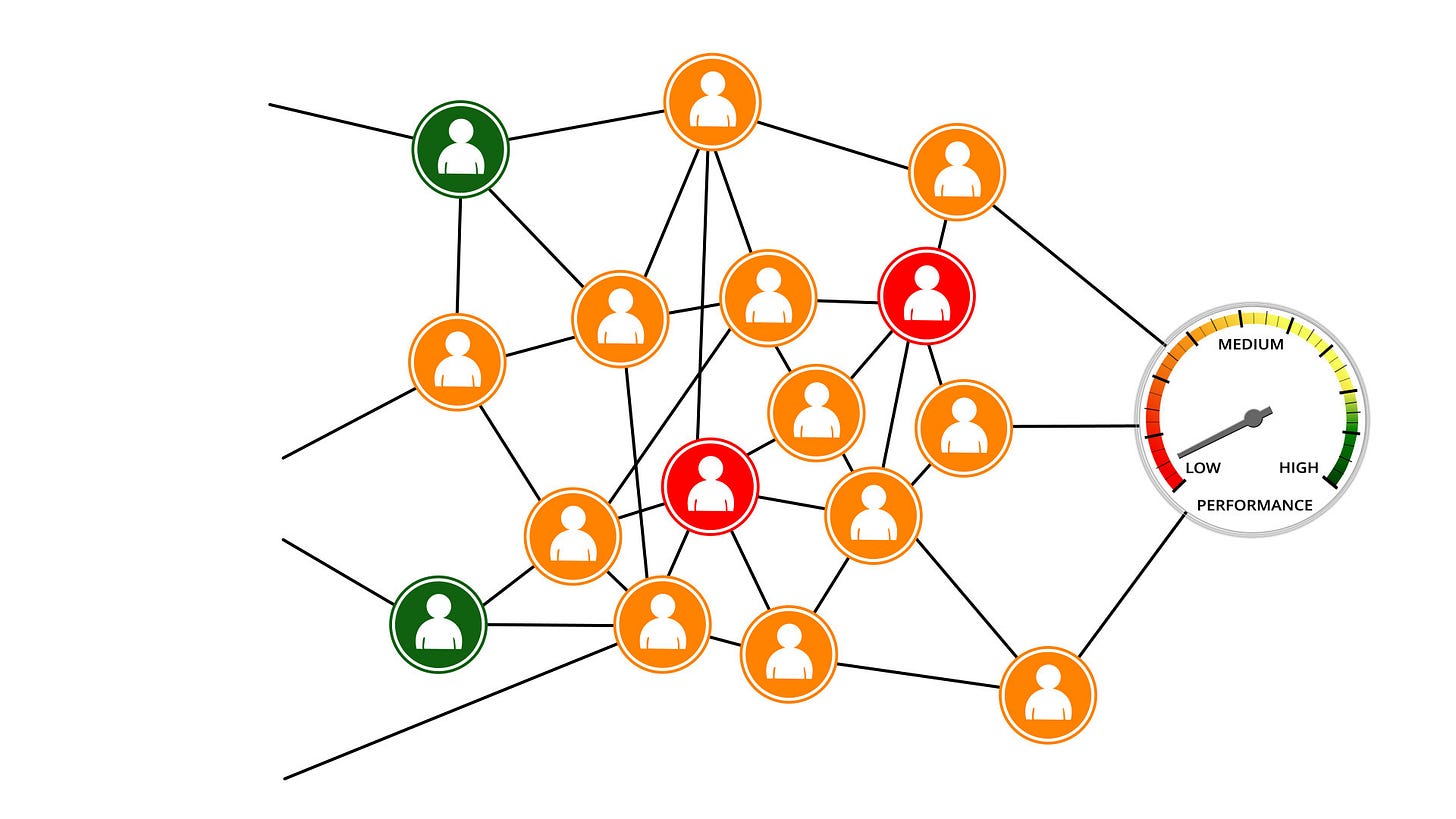

The problem with trying to create a future-fit culture using traditional methods — 1) allowing a mainstream consulting firm to impose a one-size-fits-all, cookie cutter, so-called “best practice methodology”, or 2) putting everyone through sheep dip training, or 3) hiring a coach for the executive team9, or 4) publishing mission, vision, and values statements — is that all these approaches fail to focus precisely enough and deeply enough on shifting the unique-to-this-organisation-and-its-context key influencer mindsets.

As a result, instead of the few key influencer “reds” in Figure 4 above becoming “greens” as shown in Figure 5 above, more of the current “greens” turn “orange” — shown in Figure 7 below.

The net effect of misguidedly failing to identify, enable, and support the necessary shifts in key influencer mindsets is to entrench outdated legacy habits even more deeply, pouring yet more concrete around existing obstacles, blocks and barriers to the organisation’s capacity to become fit for a increasingly uncertain and unpredictable future.

Questions for reflection

Who are the actual key influencers in your organisation?

Do they operate from a 2D3D mindset or are they trapped their own inevitably biased, limited, and one-sided 2D perspective?

What role might you play in creating conditions that are more conducive to key influencers adopting 2D3D mindsets?

Intentional Revolutions (1996) p12.

Ibid (Intentional Revolutions).

I describe the seven channels and how they influence the organisational culture in this previous article.

An organisation’s culture is the system of mindsets forming and informing people’s awareness of the way we do things round here. For more detail on this way of understanding organisational culture see this article on Seeing Culture.

Ibid (culture as “system of mindsets”).

Ibid (2D3D innovative mindset).

Ibid (2D3D innovative mindset).

The key influencers are not always on the senior executive team — and not all the senior executives are key influencers.