“He that will not apply new remedies must expect new evils; for time is the greatest innovator.” — Francis Bacon (1625) 1

Time has caught up with this old remedy: “Leadership defines what the future should look like, aligns people with that vision, and inspires them to make it happen”. 2

You can immediately see how, in our increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world, this approach to leadership no longer works:

Who could have predicted:

The 2020 global pandemic and lockdowns?

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine?

The ever-deepening political polarisation?

The ongoing societal schisms, conflicts, and upheavals?

The dynamically disruptive effects of technologies like artificial intelligence?

In such a world, how can any senior executive realistically be expected to possess the godlike prescience to “define what the future should look like”?

That’s why traditional prediction-based planning must be replaced by future-fit cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness.

This requires organisations to embrace a new way of conceiving leadership, as foreseen by my former colleague Dr Peter Senge back in 1999: “Leadership is the capacity of a human community to shape its future”. 3

If leadership is the capacity of a human community to shape its future, how much of that capacity does the typical organisation currently unlock?

The answer is not very much — which is why forward-thinking senior executives increasingly recognise the urgent need to create future-fit entrepreneurial cultures.

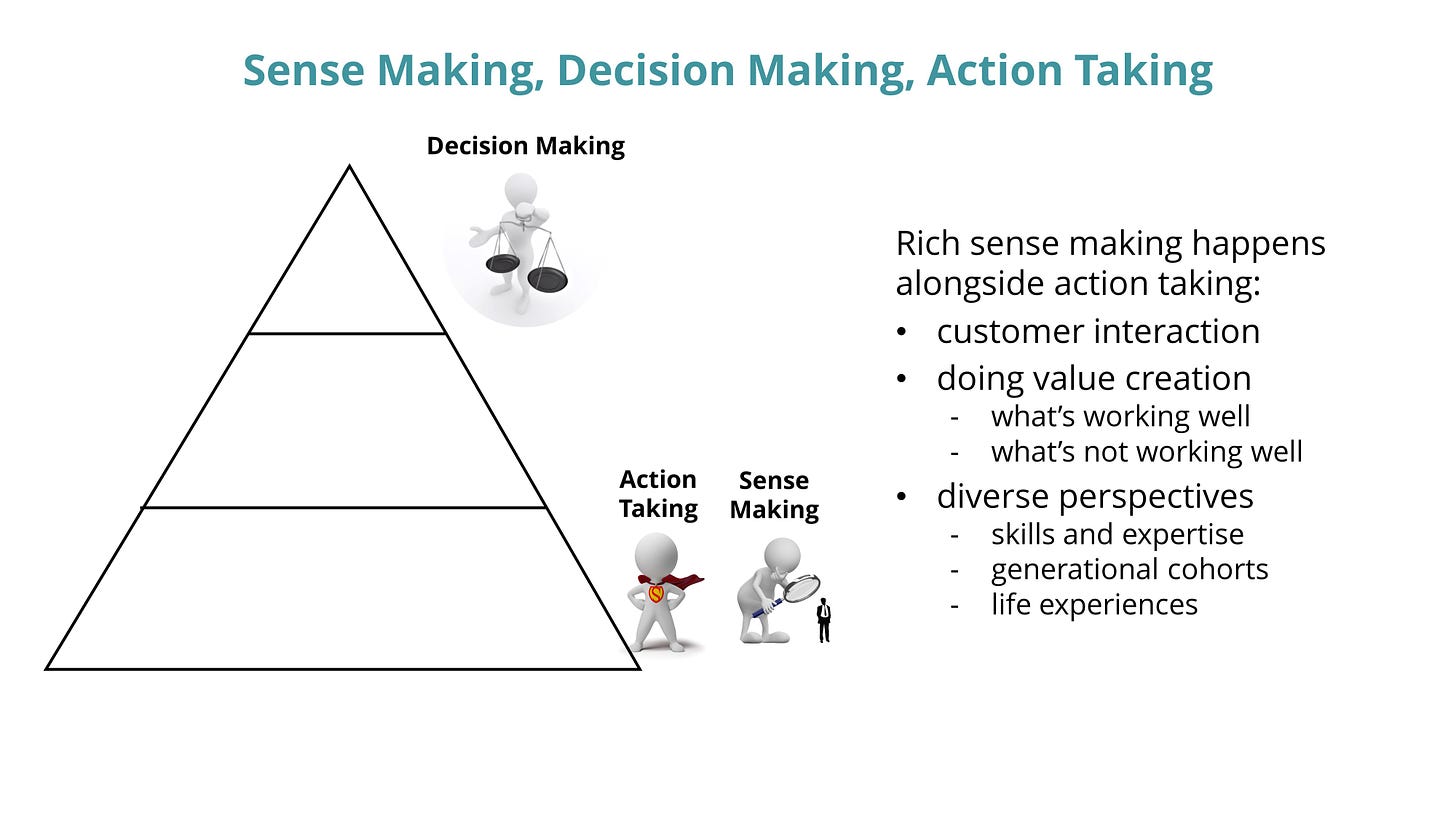

Ultimately, whether an organisation manages to unlock more of its capacity to shape its future depends on how, and how well, it does three things:

How, and how well, it makes sense of itself, its context, customer base, customer expectations, and customer perceptions of value – all of which are changing ever more quickly and in ever more unpredictable ways.

How, and how well, the organisation makes decisions about what to do and what not to do.

How, and how well, it takes action based on those decisions.

In addition, a future-fit culture depends on how, and how well these three activities — sense making, decision making, and action taking — are joined up, iterated, embedded, and distributed throughout the organisation.

Here’s an exercise I often do to highlight why organisations have had so little success in creating future-fit cultures, despite the huge amounts of time, energy, and money they’ve invested in failed efforts over the past 30-40 years.

I show a image of a traditional organisational pyramid — like this…

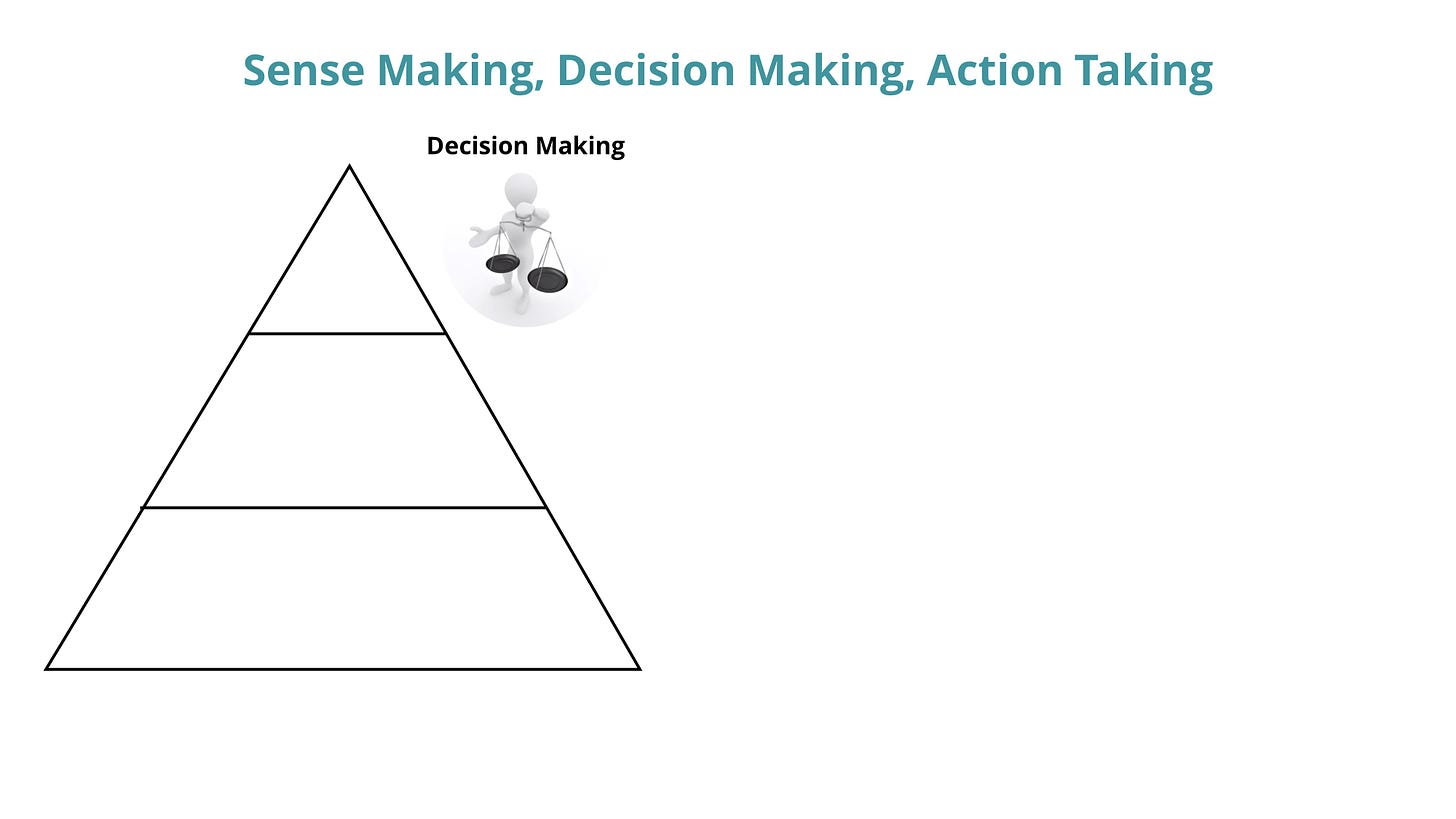

… and ask them to point to where the decision making happens.

Naturally they point to the top, towards the senior executives — like this:

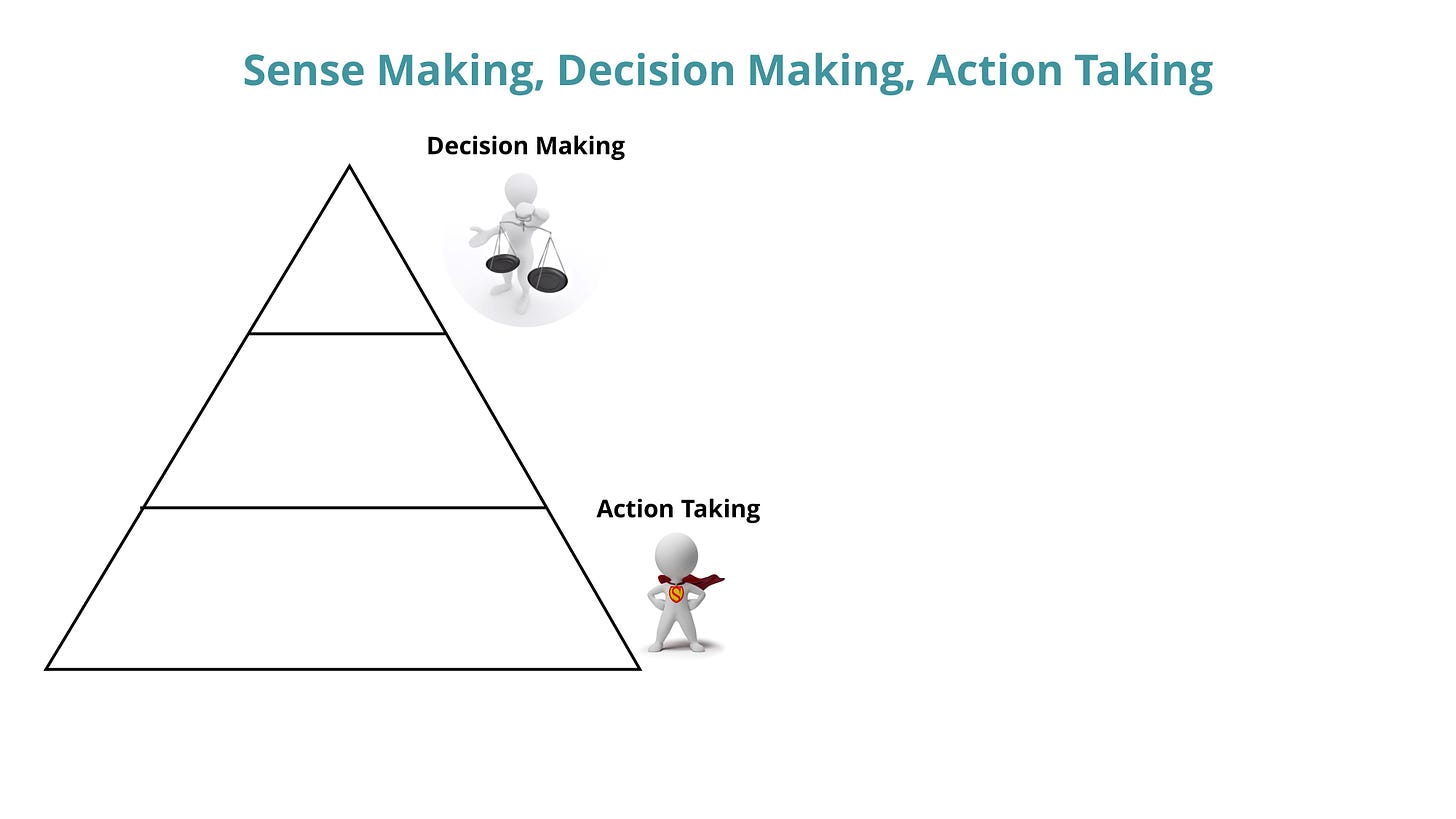

Then I ask them where the action taking happens — and they readily point in the opposite direction: to the customer facing people, the troops on the front line, the workers at the coalface, the people on the ground, where the rubber meets the road — like this:

But when I ask them where the sense making happens, they generally look a bit blank.

That’s fully understandable, because the prevailing organisational orthodoxy doesn’t explicitly identify sense making as every bit as vital as decision making and action taking.

But after some reflection, people soon recognise that the richest sense making in an organisation happens alongside the action taking — for obvious reasons:

The richest sense making happens alongside the action taking because that’s where people interact with customers and pick up their evolving perspectives, preferences, and priorities.

It’s where the vast majority of value creation happens, so it’s where people know what’s working well and not so well; where the bottlenecks are; where workarounds are required; and where things fall down the cracks.

And it’s where maximum diverse perspectives come together from different people with different skills, from different generations, with different life experiences, interests, and values.

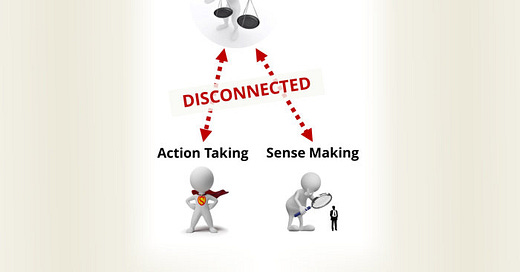

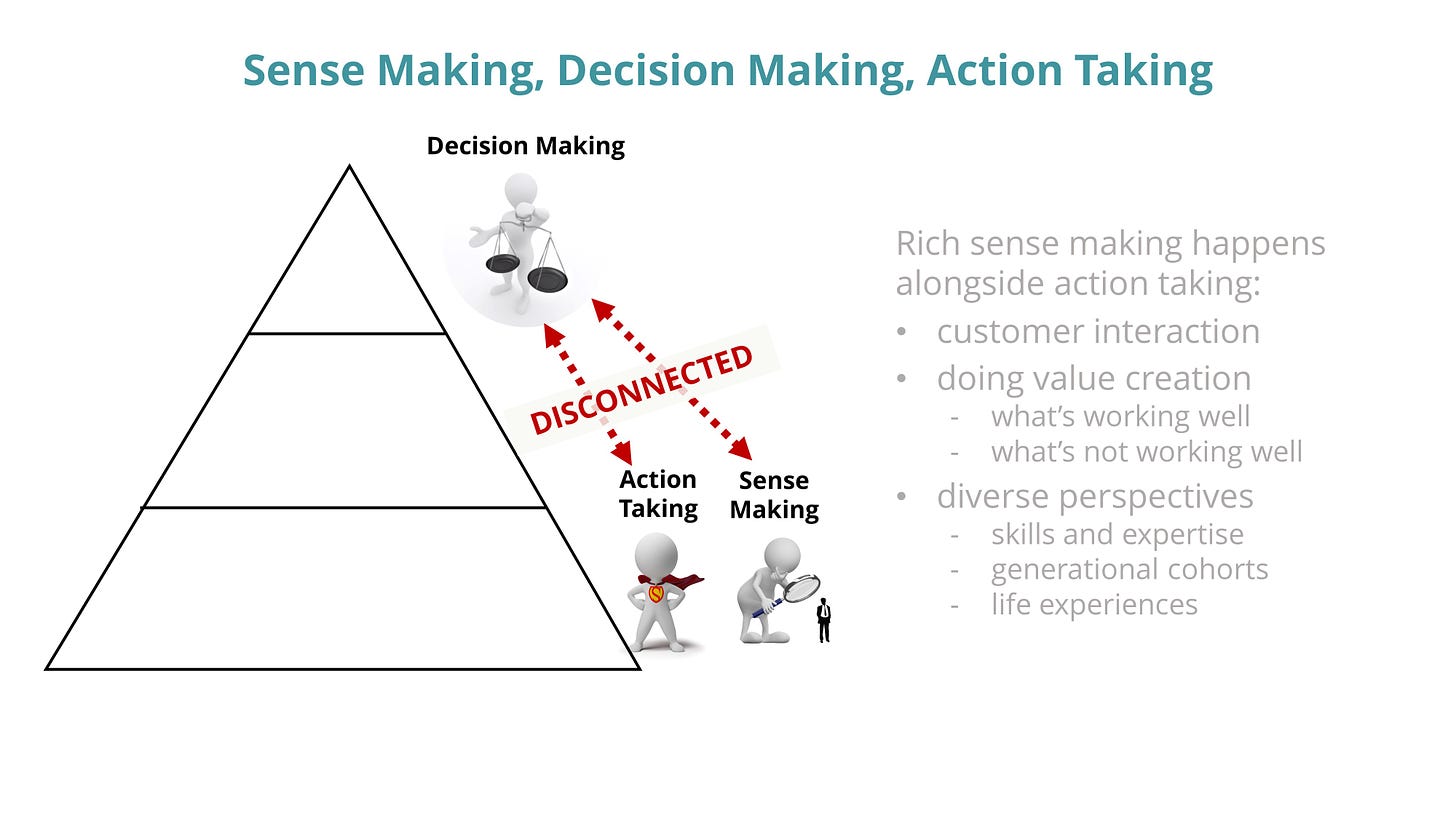

What this means, particularly in large organisations, is that decisions made at the top are often inadequately informed by the rich, dynamic, vitally important sense making that’s always going on alongside the action taking in the organisation.

As a result, when decisions made at the top reach the people on the ground who are expected to put them into action, they often don’t make much sense.

This Double Disconnect — firstly “up the pyramid” between sense making and decision making, and secondly “down the pyramid” between decision making and action taking — is getting progressively worse due to the increasing pace, uncertainty, and unpredictability of change.

The Double Disconnect is a fundamental barrier to creating an entrepreneurial culture.

And it all stems from the old orthodoxy that the role of a senior executive is to “make decisions”. 4

In an entrepreneurial future-fit culture, the role of senior executives is not to “make decisions” but to “create conditions” — conditions in which sense making, decision making, and action taking become ever more tightly coupled, rapidly and repeatedly iterated, deeply embedded and widely distributed so that good decisions get made and implemented continuously, throughout the whole organisation. 5

Next week’s article — Situational Blindness — explores what happens when people in the body of the organisation are asked to take action on decisions that don’t make sense, why this smothers, stifles, and strangles the emergence of future-fit entrepreneurial cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness, and why organisations have consistently failed to address the Double Disconnect effectively.

Questions for Reflection

Do you recognise the Double Disconnect from time you’ve spent in, or working alongside other people in, the body of an organisation?

If you’ve spent time as a senior executive decision maker, or working alongside senior executive decisions makers, do you think the Double Disconnect is not a problem in your organisation?

In organisations where I’ve described it, the people closest to the action taking inevitable recognise the Double Disconnect. However, senior executives in those very same organisations tell me that although they can see how it might happen in some organisations, it doesn’t happen in theirs. Why might these conflicting perspectives be so prevalent?

From Essays Or Counsels, Civil And Moral, Of Francis Ld. Verulam Viscount St. Albans (1625) Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St. Alban KC (22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626)

The legacy orthodoxy of leadership from Harvard Professor John Kotter’s book Leading Change (1996, revised 2012).

Peter was President of the Society for Organisational Learning when I served on its Global Leadership Team from 2009-2015. This definition appears in the third book in The Fifth Discipline series, The Dance of Change (Senge et al 1999) p16.

See this previous article on why Senior executives must give up their decision rights.

See this previous article on The truth about leadership.