Situational Blindness

Why organisations are destroying their own capacity for value creation

“We differ, blind and seeing, one from another, not in our senses, but in the use we make of them, in the imagination and courage with which we seek wisdom beyond the senses.” — Helen Keller 1

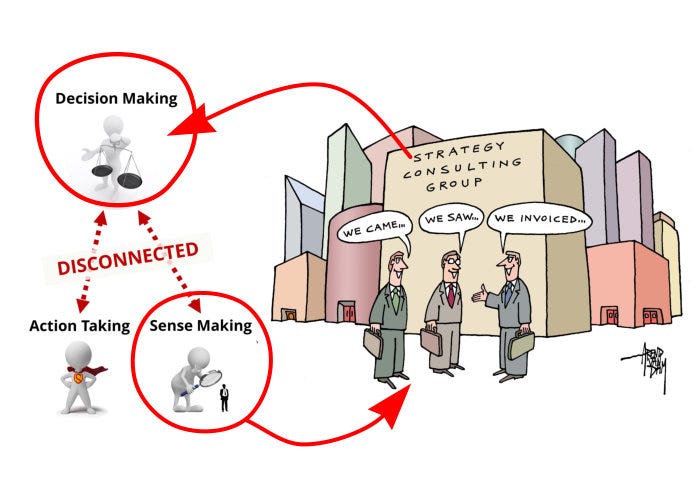

In a previous article I described the Double Disconnect — firstly between sense making and decision making, and secondly between decision making and action taking — that prevents organisations from thriving in today’s increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world. 2

The Double Disconnect doesn’t get addressed because, despite being glaringly obvious to people in the body of organisations, it’s all but invisible to senior executives with the power, and responsibility, to address it.

This situational blindness stems from the legacy senior executive perception that their main role is making decisions, whereas in an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world their role is not making decisions but creating conditions — conditions in which good decisions get made and implemented by people throughout the organisation on an ongoing, dynamic, and iterative basis. 3

A major implication of this shift in role is that senior executives must let go of the comforting chimera of prediction-based planning, and focus instead on creating conditions for emergence of a future-fit culture of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness. 4

One of the most debilitating consequences of the Double Disconnect is that when decisions reach the people tasked with putting them in action, they often don’t make sense.

And, faced with decisions that don't make sense, individuals essentially have three options for taking action:

Option #1 – Just do it.

Imagine spending your days doing things that don’t make sense, just because you’re told to.

You’d be hard pushed to avoid descending into a general state of apathy, disillusionment, and disengagement.

That’s neither good for organisational performance nor personal wellbeing.

Is it any wonder engagement scores are as abysmal as they are counterproductive?

Why counterproductive?

Because engagement in organisations is generally seen as the purview of HR people who have little influence over the drivers of engagement — such as whether decisions make sense to those supposed to enact them.

All HR can really do about engagement is measure it — and, as the old farming adage points out, weighing a pig doesn’t make it grow any faster.

Option # 2 – Question the decision.

This may sound like the only responsible thing for people to do when asked to enact decisions that don’t make sense.

But senior executives who see their role as “making decisions” always have — unsurprisingly — many more decisions to make.

In fact, they usually have more decisions to make than they have time and mental bandwidth for.

And, focused on their next decisions, they rarely welcome requests to revisit ones they’ve already made.

So, those who question previous decisions are likely to be told, more or less directly, “just do it”.

Experience this a few times and you’ll likely:

Join the ranks of the disengaged who choose Option #1

Descend deeper into apathy, cynicism, and disillusionment

Look for a better job where your contribution to sense making is seen as an asset, not a liability

Scale back your efforts to the minimum required to keep your job — an increasingly common phenomenon that has recently acquired the label “Quiet Quitting”

-

As with Option #1, performance, engagement, and wellbeing all tank, whilst Option #2 brings the added “bonus” of boosting attrition…

It’s not hard to see how Options #1 and # 2 fuel a progressive decline in the intrinsic motivation that’s central to a future-fit entrepreneurial culture of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness

Option # 3 – Do something that does make sense instead.

This creative solution is a bit risky to take on your own.

It takes courage — and people only choose Option #3 if they’re deeply committed to the organisation and its future.

And because it’s risky, those who choose Option #3 rarely do so alone, but enrol trusted colleagues in collective sense making, decision making, and action taking.

Ironically, this collective sense making, decision making, and action taking is precisely the behaviour organisations need to cultivate if they’re to become future-fit.

However, the deeper irony is that these highly committed people are doing this despite what they’re being asked to do — not because of it.

Adding further irony is the fact that this “non-compliance” or “disobedience” mustn’t get back to the decision makers or there’d be trouble.

Amongst those who choose Option #3, there may be a few who don’t entirely hide their non-compliance but communicate it in subtle and sophisticated ways to others in the know.

These ironists are often seen as troublemakers, but in reality they help maintain positive spirits whilst, at the same time, helping bridge the gap between official decisions and appropriate actions — all stemming from the Double Disconnect. 5

However, despite the contribution of these brave ironists to bridging the gap, most senior executives plough on in blissful ignorance when organisational value is being created despite, not due to, their decisions…

The double disconnect between sense making, decision making, and action taking emerged, evolved, and embedded itself over a long time, when the world was changing much more slowly.

It was a world where there was time for senior executives to make decisions, communicate them, and when they didn’t make sense have people choose Option #3, take different action, cover up their non compliance, and generate results.

If things got really out of whack, senior executives could always hire a traditional management consulting firm to “help”.

That “help” consists of the consulting firm mobilising a large number of junior consultants to ferret around and tap into the rich sense making that’s always already happening in an organisation.

Then the partner in charge of the consulting work interprets the rich sense making, adds a judicious helping of marketing spin, presents the “findings” to the senior executive client and advises them on next steps — typically including further “essential” consulting work... 6

Meanwhile, the people who know what’s actually going on in the organisation, and who care most about its future, and whose rich insights were co-opted to generate revenue for the consulting firm — as opposed to creating value for their own organisation — get increasingly ignored, marginalised, and alienated.

This dysfunctional dependence on external “help” perpetuates situational blindness, destroying the organisational capacity for value creation in an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world.

People are becoming more aware of this with Mariana Mazzucato’s recent exposé of the phenomenon in her book “The Big Con — How the Consulting Industry Weakens our Businesses, Infantilizes our Governments and Warps our Economies”. 7

This progressive capability destruction will continue to worsen until senior executives have the deep realisation that their role is not “making decisions” but “creating conditions” that unblock, unlock, and unleash the human capacity within their own organisation, thereby creating a future-fit entrepreneurial culture of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness. 8

Questions for Reflection

Have you been in situations where you were expected to take action on decisions that didn’t make sense?

Which of the three options did you choose?

What action is being taken to address the double disconnect and reverse the trend of progressive capability destruction in your organisation?

Helen Keller was an American writer and social activist; an illness at the age of 19 months left her deaf and blind. The quote is from The Five-sensed World (1910).

See this previous article explaining why Senior executives must give up their decision rights.

For more on this topic, see this previous article Creating conditions for emergence.

I’m indebted for this insight to my colleague Dr Richard Claydon whose PhD thesis was on the subject of organisational irony as a strategy for living in modern organisations.

“Hired Help that Hinders” is the fifth and most systemically serious of the Five Fatal Habits that have consistently prevented organisations from creating future-fit cultures of innovation, agility and adaptiveness over the past30-40 years.

Ibid “Senior executives must give up their decision rights”.