Creating Conditions for Emergence

Emergence is the only way to handle the increasing complexity of our world. How can you create conducive conditions..?

“The most destructive idea in existence: I am greater than you; you are less than me. This is the source of all human misery”. – Tyson Yunkaporta 1

The essential feature of a future-fit culture is that it encourages, enables, and engages people to combine their different perspectives, insights, and ideas to co-create new value in iterative, emergent, regenerative ways. 2

In our formal schooling, few of us develop the capacity to appreciate someone bringing radically different perspectives to a topic we feel we already know, challenging our current beliefs, and highlighting ways of seeing the familiar that we hadn’t considered before.

This can be an especially powerful experience when those different perspectives challenge deeply held assumptions about the nature of reality.

Someone who has done a masterful job of this is Tyson Yunkaporta, a member of the indigenous Apalech Clan whose homeland is in far north Queensland, Australia.

Yunkaporta is also a senior lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges at Deakin University in Melbourne, and in June 2020, published the bestseller ‘Sand Talk — How indigenous thinking can save the world’.

What makes the book unique is that it performs a role reversal on traditional anthropology.

Instead of doing what previous books have done — looked at indigenous knowledge from a western perspective - Yunkaporta flips the mirror and looks at western society though an indigenous lens.

What he sees is not a pretty sight:

“Where you used to have family and community now you're going to have the economy and the state. And they'll say: We're going to provide all the things for you that land used to provide. But you have to sell us a third of your life.

And you're going to have to spend another third sleeping. Oh, and by the way, a sizeable chunk of the third that's left you're going to have to spend on commuting, life maintenance tasks, etc.

And you're not going to be getting any exercise anymore, so you need to set aside an hour for that. But that's alright – we're going to provide you with these little indoor spaces where you can lift heavy things that don't need lifting and pedal on a bike that goes nowhere and run even though nothing is chasing you and you're not chasing anything and you're not in a hurry.

And you're going to do all those pointless tasks over and over and over again until you die – and that's progress.” 3

What I personally found most striking about Yunkaporta’s book, and in interviews I’ve seen with him since, is how indigenous knowledge reflects and represents the innate human capacity for collective value co-creation that’s been central to my work over the past 35 years.

A great example of this is: “Solutions to complex problems take many dissimilar minds and points of view to design, so we have to do that together, linking up with as many other us-twos 4 as we can to form networks of dynamic interaction.” 5

This describes the practice of cultivating the 2D3D mindsets that enable people to combine their different perspectives in dynamic ways to continuously co-create new value. 6

Yunkaporta is similarly scathing of the simplistic ‘best practice solutions’ often peddled as panaceas for systemic complexity:

“Anybody who thinks they've got a solution or they have a plan or a design or anything like that – they're an idiot. You can't. Dynamic systems don't operate like that. You have a thing called emergence. We know this. We know the science on it and emergence is the only thing that can deal with these kind of complexities. All you can do is foster the conditions for emergence.”

To further understand those conditions, another deeply insightful and highly readable book is Damon Centola’s “Change – How to Make Big Things Happen”. 7

Centola revisits one of social science’s core themes – the strength of weak ties 8 – and demonstrates that can be misleading when seeking social change at scale.

Centola’s research confirms that simple contagions – ideas that resonate with the prevailing mindsets of a receiving local network – can travel well over the narrow bridges provided by weak ties.

But the complex contagion required to bring about substantive cultural change propagates differently – via the wide bridges that embed social norms in a network.

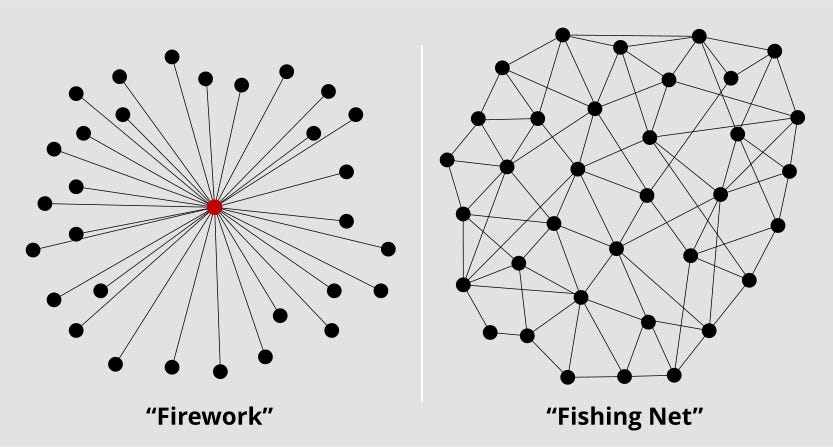

He identifies two main types of network configuration – the “firework” and the “fishing net”.

The firework has many social ties back to a central ‘node’. That node is an influential individual whose mindset, attitudes and behaviours directly impact many other direct connections.

By contrast, the fishing net has multiple social ties between multiple individuals. Consequently, no individual wields a dominating, distorting or decisive influence on the whole.

The fishing net form of network creates conditions for emergence through the multiple relationships that enable and enrich collective sense making.

When collective sense making works well, decision making becomes much easier because everyone involved can see why the decision makes sense. Then action taking follows more fluidly.

That’s vital for a future-fit culture of innovation and agility where sense making, decision making & action taking must be ever more tightly coupled, rapidly and repeatedly iterated, deeply embedded and widely distributed throughout the organisation.

A fishing net form begins to emerge as key influencers relax their constraining grip on the network.

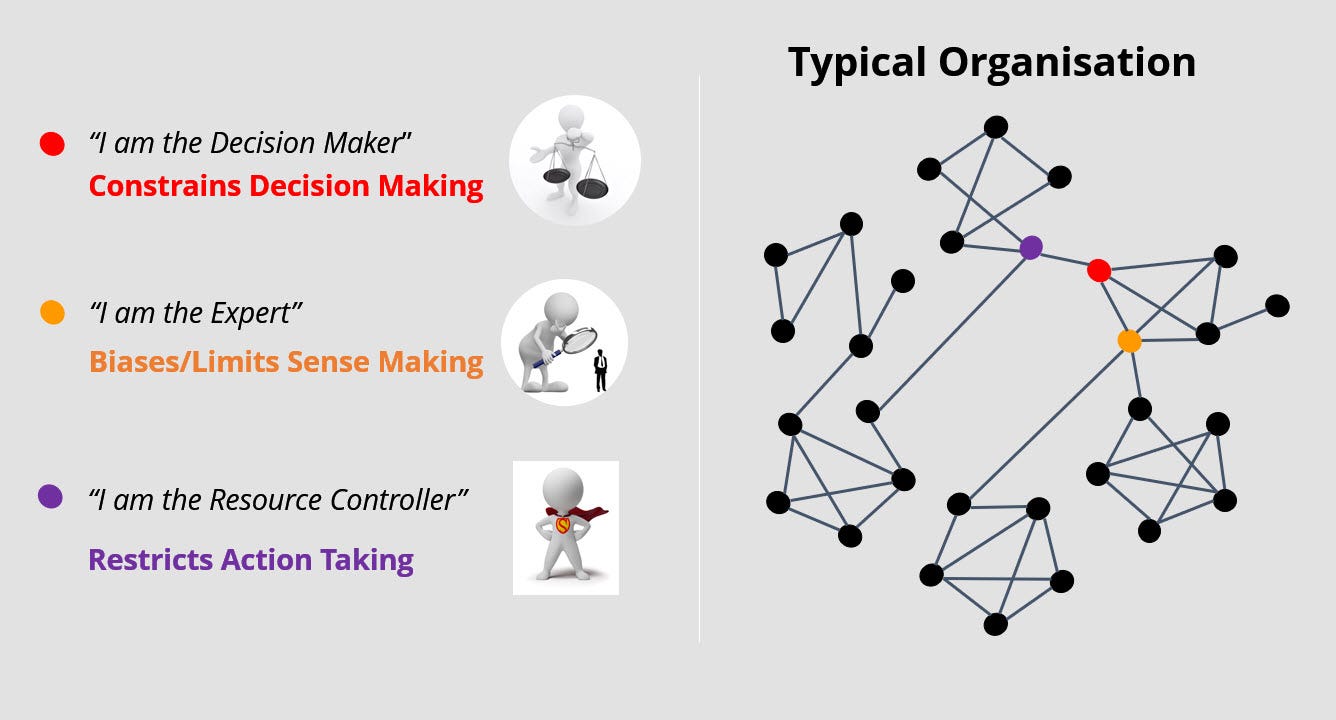

In the dozens of organisations I’ve poked about in over the past 35 years, I’ve repeatedly encountered three key influencer mindsets that ‘constrain the fishing net’, where the individual concerned gains personal influence over others and simultaneously constrains the collective capacity for emergence:

“I am the decision maker” – creates a decision bottleneck, generates self-imposed stress for the ‘decision makers’, and leads to poor quality decisions due to overload and fragmented attention.

“I am the expert” – distorts, dominates, and downgrades collective sense-making, vastly curtails the capacity for the emergence of new ideas, and contributes to poor quality decisions due to biased and patchy sense making.

“I am the Resource Controller” – constrains the availability of required resources by saying ‘no’ too often and prevents people from taking the actions necessary to create value and/or to flush out new sense making insights.

The highest leverage, lowest risk way to foster conditions for emergence is to focus precisely and deeply on shifting the mindsets of the key influencers whose mindsets, and therefore attitudes and behaviours, currently constrict and constrain the network

Here’s Tyson Yunkaporta again:

“Respectful observation and interaction within the system, with the parts and the connections between them, is the only way to see the pattern.

You cannot know any part, let alone the whole, without respect.

You cannot come to knowledge without it.

Each part, each person, is dignified as an embodiment of the knowledge.

Respect must be facilitated by custodians, but there is no outsider-imposed authority, no ‘boss’, no ‘dominion over’.

While senior people ensure the processes and stages of coming to higher levels of knowledge are maintained with safety and cohesion, there is no centralised control in Aboriginal societies.” 9

It takes courage for senior executives to let go of the illusion that they can know everything and control everything.

They never could of course - but as the world has become ever more uncertain and unpredictable, the old illusion or delusion that they could has fallen away to reveal the reality that only by unlocking collective capability can organisations hope to thrive in the future.

As Yunkaporta points out: “It is difficult to relinquish the illusions of power and delusions of exceptionalism that come with privilege. But it is strangely liberating to realise your true status as a single node in a cooperative network.” 10

That liberation is largely the sense of relief that comes from not having to pretend to know it all and, by escaping the associated Seeing-Being Traps,11 becoming able to combine your insights, ideas and interests with those of many others to co-create new value in new ways.

That’s how successful senior executives of the future will play their part in fostering the conditions for emergence and flourishing of future-fit cultures.

‘Sand Talk - How indigenous thinking can save the world’ [Loc 315]. References below [Loc nnn] are the location numbers for the Kindle e-book.

Value in all forms, not just monetary.

I've left out a few colourful adjectives here, from the first few minutes of Rebel Wisdom’s Alexander Beiner's interview with Yunkaporta after the book launch.

“Ngal” is a dual first person pronoun common to indigenous languages but not present in English. Yunkaporta uses the term “us-two” in English and explains that the book is written to engage the reader as his dialogic partner – the ‘other half’ of us-two. Ibid. [Loc 240]

Ibid. [Loc 243]

The 2D3D mindset at the heart of a future-fit culture is described in this 6 minute video.

Damon Centola’s ‘Change’ (Kindle version) is available here.

The Strength of Weak Ties is a famous 1973 paper from Mark Granovetter of Johns Hopkins University

Ibid. [Loc 957]

Ibid. [Loc 984]

This post explores the Seeing-Being Trap