“Nelson Mandela reminds us that it always seems impossible until it is done”. — Barack Obama1

In 35 years hands-on experience helping organisations throughout Europe, Asia, and the US create future-fit cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness I’ve often encountered deeply entrenched beliefs about what is and isn’t possible.

And not just in others.

I’ve run into some seriously limiting perspectives of my own, rooted in uncritical acceptance of unexamined assumptions and received wisdom that only fell away when I’d witnessed, in practice, things I’d previously perceived impossible.

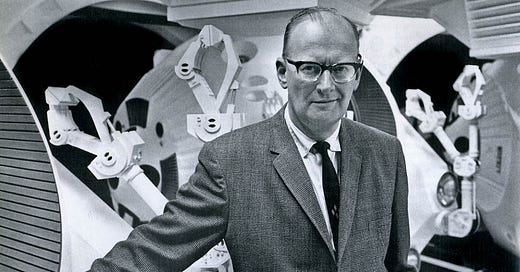

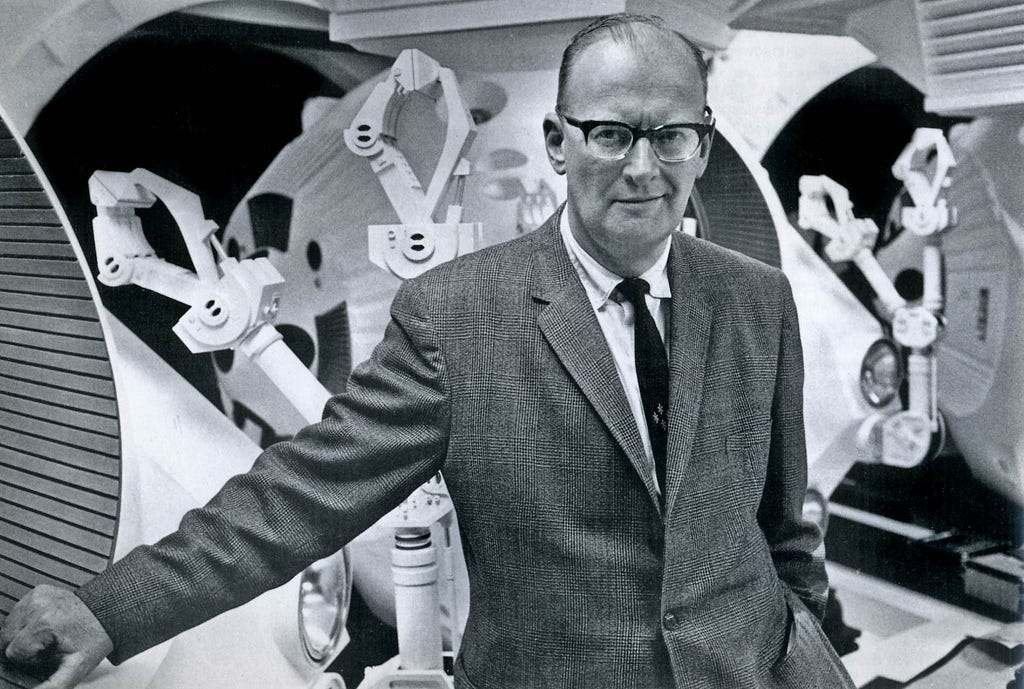

More on that shortly, but I first want to frame this exploration using the three laws put forward by Sir Arthur C. Clarke, CBE, FRAS.2

Clarke’s Three Laws:

“When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong”. 3

“The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible”. 4

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. 5

Law #1 — Distinguished elderly scientists

Those of us with backgrounds in science, technology, engineering, and/or mathematics like to consider ourselves to be rational, dispassionate, and objective — purely influenced by “the facts”.

However, as Clarke’s First Law points out, established experts frequently fail to embrace ideas that challenge the status quo and, consequently, their status.

Max Planck, founding father of quantum theory expressed similar sentiments in his pithy observation of how science actually progresses:

“A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die — and a new generation grows up that is already familiar with it”. 6

This is sometimes paraphrased as “Science progresses one funeral at a time”.

But Clarke’s First Law doesn’t just apply to the great and the good in the higher echelons of the scientific community.

The phenomenon also affects individuals who — whilst perhaps not exactly justifying the labels “distinguished”, and/or “elderly”, and/or “scientist” — are so in thrall to their present ways of seeing they’re unwilling or unable to consider anything that goes beyond them.

I have, for example, encountered many individuals over the years who asserted with great confidence that organisational cultures simply cannot be created.

It’s deceptively easy for “I don't know how to do it” to be mistaken for “It can’t be done” — if you constrain possibility to the confines of your current convictions.

Law #2 — The limits of the possible

On 14th October 1947, US Air Force Captain Chuck Yeager — piloting the Bell X-1 rocket-powered plane Glamorous Glennis — became the first person to break the sound barrier, reaching 700mph / 1,127km/h / Mach 1.06.

Only he didn’t really break the sound barrier — because no such barrier actually exists.

However, until Yeager’s feat, “many feared that supersonic flight was impossible because of an invisible barrier that could destroy aircraft”. 7

As Yeager himself later commented:

“I realized that the mission had to end in a let-down because the real barrier wasn’t in the sky, but in our knowledge and experience of supersonic flight.” 8

Similarly, to thrive in an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world, organisations must venture beyond the legacy limits of knowledge and experience perpetuating perceptual barriers to future potential.

That’s especially challenging for anyone who thinks they already know all they need to know, don’t want their perceptions of self-importance threatened, and refuse to step outside their current zone of comforting self-delusion.

Law #3 — Magical technologies

Our house here in Cambridge UK was built in 1870.

I’ve often wondered what its original occupants would make of the washing machine, tumble dryer, refrigerator, freezer, microwave oven, and induction hob — and that’s just what they’d encounter in the kitchen.

What about the heat pump and thermal insulation that keeps my garden office comfortable all year round at low cost and minimal environmental impact, and its high-speed internet connection that allows me to connect in real time, day or night, with clients and colleagues as far afield as Australia, China, and the USA.

But you don’t need to go back150 years. Most of the technologies we take for granted today would have been indistinguishable from magic just a few decades ago.

Importantly, Clarke’s Third Law doesn’t only apply to technology in the narrowly defined sense of “physical sciences applied for practical purposes”.

It applies equally in the broader original meaning of the Greek tekhnologia:“the systematic treatment of an art, craft, or technique” — which in turn stems from tekhnē: “art, skill, craft in work; method, system, an art, a system or method of making or doing”. 9

Within this broader definition, I’ve had several indistinguishable from magic experiences over the years whilst helping clients create future-fit organisational cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness.

One stands out as particularly pivotal — involving the dropping of a limiting belief I didn’t realise I’d had, and significantly influencing my work ever since.

I’ve previously described in detail the “aha” moment of seeing how I’d been unconsciously held back by the false — but widely-accepted received wisdom — that culture change is inevitably a high-risk, drawn-out, and often painful process. 10

That erroneous belief was swept away once I saw, with my own eyes, what occurred in a client organisation when a few key influencers escaped the trap of their individual biased, limited, and one-sided “2D” perspectives.

In doing so they saw with their own eyes, for the first time, the hidden value in the equally biased, limited, and one-sided — albeit significantly different — 2D perspectives of other key influencers within the organisation.

As a consequence, the key influencer mindsets that ultimately systemically sustain an organisation’s culture had shifted — literally overnight — unleashing tremendous untapped human potential that enabled them to build a highly successful business together.

Their CEO, witnessing this seemingly magical transformation, asked me: “How did you do that..?”

My immediate reply was: “I wish I knew”.

I later realised the magical moment occurred when key influencers broke free from the trap of their limited and limiting 2D perspectives — this becoming a central focus of my subsequent work.

The intoxication of seeing people who had been at each other’s throats the day before, now engaging enthusiastically with each other to create real value, made me realise I didn’t want to spend my career doing anything else.

The buzz I felt witnessing this explosion of collective human creative energy made me wonder if Bryan Ferry had been wrong when he sang “Love is the drug”. 11

I’ve subsequently had similar experiences with people in many organisations, seeing them shift from profound feelings of frustration at being unable to get things done, to levels of enthusiasm, energy, and engagement they never believed possible.

Going from hating their work to loving it.

So maybe Bryan was right after all…

I’ve encountered plenty of people who steadfastly dismissed the possibility of achieving transformational culture change, some even labelling it “magical thinking”.

But as Clarke’s Third Law states, things often appear magical when you don’t understand how they work.

And very few people have a deep, real-world, actionable understanding of how organisational cultures form, and therefore how they can be reformed.

It’s therefore understandable that they dismiss the possibility — and fail to wake up until its too late and one of their competitors has done it instead.

Questions for reflection

Where do you observe Clarke’s Three Laws in operation..?

Where do you personally risk mistaking “I don’t know how to” for “It can’t be done”..?

Who might you engage with to open your eyes to new possibilities..?

Remarks by President Obama at Memorial Service for Former South African President Nelson Mandela at First National Bank Stadium, Johannesburg, South Africa, on 10th December 2013.

Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008) was an English science writer, futurist, and science fiction writer, co-authoring the screenplay for the 1968 blockbuster “2001: A Space Odyssey” .

The First Law was first published in Clarke’s 1962 essay “Hazards of Prophecy: The Failure of Imagination” in the collection “Profiles of the Future: An Enquiry into the Limits of the Possible”. (1962). At the time it was known simply as “Clarke’s Law” — Laws #2 and #3 appearing later.

The Second Law appeared as an observation in the Hazards of Prophecy essay (Ibid). Its status as Clarke’s Second Law was subsequently conferred by others.

The Third Law is the best known and most widely cited. It was published in a 1968 letter to Science magazine and included in the 1973 revision of the Hazards of Prophecy essay (Ibid).

“Scientific Autobiography and Other Papers” by Max Planck (1949).

“Breaking the Sound Barrier: Chuck Yeager and the Bell X-1” article for the Smithsonian US National Air and Space Museum by Bob van der Linden, 13th October 2022.

Ibid (van der Linden).

Etymology of “technology” at Etymonline.

See the previous article Focus on key influencers.

"Love Is the Drug" appears on Roxy Music's fifth studio album Siren, and was released as a single in September 1975. See the ever dapper Bryan crooning it in the music video here.