“Who are you? who, who, who, who — I really wanna know. Come on, tell me who are you, you, you, who are you?” — The Who 1

In a previous article, Back to BASICs, 2 I described how social psychologist Erving Goffman (1922 - 1982) drew on earlier work by Kenneth Burke (1897 - 1993), and William Shakespeare (1564 - 1616) in developing the understanding that each of us is an actor playing various parts on the stage of life.

But how often do we lose sight of this, and identify with the parts we play instead?

The difference between basing our awareness of self in the parts we play as opposed to the actor playing those parts is not just of academic interest — it has huge implications for our actions and interactions in daily life.

In the Back to BASICs article, I highlighted the power of the pig metaphor, which I first encountered at a lecture here in Cambridge in 1997 given by Professor Gareth Morgan, author of Images of Organization. 3

He used it to illustrate how our being influences our seeing:

“When a veterinarian sees a pig, the pig looks like a patient; to a farmer, the same pig looks like money; to a butcher, it looks like meat. We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are”.

In other words, our awareness of self creates the way we see things.

But it’s not a one-way street.

The way we see things challenges or confirms our awareness of self.

In other words there’s a reciprocal relationship between awareness of self and awareness of context in which we find ourself — in both senses of the word “find”.

Just as an eye can’t see itself directly, only its reflection, we can’t directly be aware of our awareness of self.

But what we can do is pay greater attention to how we perceive the context, because that reflects the awareness we’re bringing to it.

In other words, using Morgan’s pig metaphor again, if the pig looks like a patient, we’re seeing it from the awareness of a vet.

The awareness of self, in this case of being a vet, dictates what the pig appears to be, in this case a patient.

Through different eyes — e.g. of farmer or butcher — the pig appears quite different.

If our sense of self becomes too closely tied to being the vet, being the farmer, or being the butcher then we’ll find it very difficult to see the validity of any perspective different to our own.

In other words, when we’re locked into a specific awareness of self, we see things as possessing qualities, attributes, or natures that seem to be inherently part of what we’re seeing.

However, the apparently inherent nature of what we see is illusory — it only seems inherent because of the eyes through which we’re seeing it. 4

The more closely we identify with what we see, the more painful it will be if we have to let go of our cherished perspective.

Or, as former US Secretary of State and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Colin Powell put it: “Avoid having your ego so close to your position that when your position falls, your ego goes with it.” 5

Our individual and collective sense making becomes radically curtailed when our sense of self is too invested in the parts we play.

This is crucially important, because it inhibits the creation of future-fit cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness, where sense making, decision making & action taking must become ever more tightly coupled, rapidly and repeatedly iterated, deeply embedded and widely distributed throughout the organisation.

I first started working with this “role vs actor” insight in the early 1990’s.

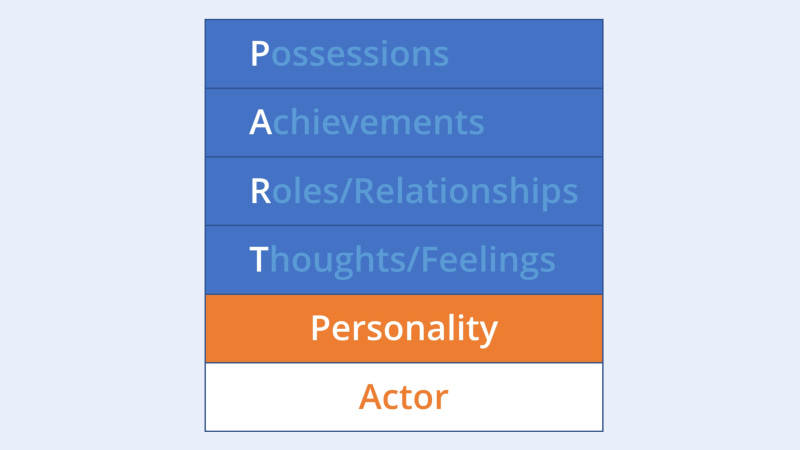

After a few years, I noticed there seems to be a hierarchy of layers to the sense of self, and therefore a corresponding hierarchy in the contexts we perceive.

As I began testing out the hierarchy hypothesis in workshops, presentations, and seminars, it evolved into what became known as the Hierarchy of Illusions. 6

Now, I’m not claiming this hierarchy is somehow a deeply embedded truth in the fabric of the universe, or even of human existence.

It’s a model, and as mathematician George Box is remembered for saying: “All models are wrong; some models are useful”. 7

The Hierarchy of Illusions is useful in seeing where we over-identifying our selves with the parts we play in daily life, so we can become more aware of ourselves as actors playing those parts. 8

Possessions

“I am my Possessions” is the topmost level of the Hierarchy of Illusions.

Have you ever noticed feeling better when you’ve just acquired something..?

In 2013 a survey of American adults found around 60% of women and 40% of men had engaged in retail therapy, buying stuff in order to improve their mood. 9

Advertisers are fully aware of this phenomenon, and are highly skilled in persuading us that a new phone, TV, or car will give us enhanced feelings of wellbeing.

Some years ago, there was an advert for the BMW 3-series car, equating its ownership with joy.

Want more joy in your life?

All you need to do is save up — or take out a loan — and get yourself a brand new BMW 3-series.

You joyfully drive it off the forecourt and take it for a spin.

Joy abounds — until you get overtaken by someone in a BMW 5-Series.

But you can always regain your joy by saving up, or taking out a bigger loan, and buying yourself your very own 5-Series.

Until you then get overtaken by a Porsche, Ferrari or Lamborghini.

And if you then buy one of those, all’s well until you get left behind by a Bugatti Veyron, Koenigsegg Gemera, or McLaren Speedtail.

Get yourself one of those, and you find someone else has a helicopter, executive jet, or if they’re Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos or Richard Branson, a space rocket.

You can of course see the pattern of escalating acquisition of things to make you feel good.

And let me be clear — I’m not advocating you should own nothing.

It’s fine to have possessions.

The problems start when your possessions have you.

Achievements

“I am my Achievements” is the next level below “I am my Possessions” in the Hierarchy of Illusions.

Just as with possessions, there’s nothing wrong with achievements.

In fact, a life without achievements would be pretty dull.

The problems start when your sense of self becomes dependent on your achievements.

I have a degree in electronics engineering.

You have a PhD in astrophysics.

We get on fine with each other unless one of us identifies with their academic achievements and then feels superior or inferior because we confuse our self with our achievements.

In her fascinating TED talk “Your elusive creative genius” (2009), Elizabeth Gilbert, author of the bestseller Eat Pray Love (2007), describes what happens when writers identify with their achievements: 10

“I recently wrote this book, this memoir called "Eat, Pray, Love" which, decidedly unlike any of my previous books, went out in the world for some reason, and became this big, mega-sensation, international bestseller thing. The result of which is that everywhere I go now, people treat me like I'm doomed. Seriously — doomed, doomed! Like, they come up to me now, all worried, and they say, “Aren't you afraid you're never going to be able to top that? Aren't you afraid you're going to keep writing for your whole life and you're never again going to create a book that anybody in the world cares about at all, ever again?”

She goes on to admit: “It's exceedingly likely that my greatest success is behind me…” but concedes “…that's the kind of thought that could lead a person to start drinking gin at nine o’clock in the morning.”

Gilbert deals with this by avoiding identifying with her achievements.

She treats the creativity that makes her achievements possible as something that visits her, not as something she makes happen.

Her job is simply to show up and put in the work.

I strongly recommend her 20 minute TED talk. 11

Roles / Relationships

“I am my Roles / Relationship” is the next level below “I am my Achievements” in the Hierarchy of Illusions.

You may have noticed it was easier to imagine not identifying with your possessions than with your achievements — with the latter feeling more intrinsically a part of you than the former.

This pattern continues as we work our way down the hierarchy — it gets progressively harder to avoid identification at each lower level.

It doesn’t help that we’re socially conditioned to identify with the roles we play in life, at work and socially.

Back in 2000, my then employer Arthur D. Little got itself into serious financial difficulties, and in the subsequent restructuring in early 2001, sold or shut down most of their UK operations.

I’d been in a unit dedicated to accelerating cultural transformation in client organisations, and my only option to remain at ADL was to shift to one of the more traditional practices.

These other practice areas operated based on the model used by the traditional finders, minders, grinders firms like McKinsey, BCG, PWC, EY, Accenture, etc.

Senior folks like me would be expected to function as “finders” — winning large projects to be staffed with lots of junior consultants — the “grinders”.

But I had — and still have — zero interest in spending my life selling work designed to mobilise hordes of junior consultants, thereby preventing the people in the client organisation from building the innovation, agility, and adaptiveness muscles in their organisation so it’s fit for an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable future.

I concluded that I needed to set up in private practice instead, but couldn’t do that without the startup capital.

Fortunately, with 18 years of continuous service in ADL Group (including 12 years with the open innovation services lab Cambridge Consultants Limited, then an ADL subsidiary), under UK law I was due a redundancy payment that proved enough to set up my business, now in its 21st year.

Consequently I was delighted to be made redundant, because if I’d left of my own accord I wouldn’t have received the payoff that got my business up and running.

Many others were less happy to be let go: “I’ve given my heart and soul to this place, working 60, 70, or 80 hour weeks, hardly seeing my kids grow up and now I’m thrown on the scrap heap”.

Role identification like this isn’t just a problem in the work context.

A colleague recently told me about a friend whose mother had spent more than thirty years raising him and his three siblings.

When the last of the four children left home, the mother had an identity crisis.

She’d invested so much of herself into being a mother she had no sense of self outside that role.

At the age of 65 she had to rediscover her self, and with her son’s help, gradually regained the awareness of being the actor who had played, and become lost in, the role of being a mother.

There’s a similar story about a woman married to a high-profile Cambridge professor who, for the sake of anonymity, I’ll call Professor Smith.

The woman would introduce herself at social gatherings as “The Wife of Professor Smith” — basking in the reflected glory of The Great Man.

Unfortunately, Professor Smith decided he liked his secretary more than he liked Mrs Smith.

Yet after the divorce, she still introduced herself as “The Ex-Wife of Professor Smith”.

Her sense of self was so deeply invested in being married to an illustrious professor that even when she no longer had that role, the role still had her.

And just to re-emphasise again, as with possessions and achievements, there’s nothing wrong with roles or relationships.

In fact it’s nigh on impossible to avoid them — and life would lack meaning without them.

But the more our sense of self is invested in roles and relationships, the harder it is to avoid being trapped.

So the question is not about having or not having roles and relationships.

The question is how much do my roles and relationships have me..?

If one of my current roles or relationships was no longer there, how much would I feel diminished?

Thoughts / Feelings

“I am my Thoughts / Feelings” is is the next level below “I am my Roles / Relationships” in the Hierarchy of Illusions.

Most of us find it very difficult to avoid identification with our thoughts and feelings.

We may even question whether we should — thinking “Wouldn’t life be utterly devoid of meaning if we didn’t identify with our thoughts and feelings?”

Not really.

We’d still have our thoughts and feelings.

It’s just they would no longer have such power to dictate our state of being.

Rudyard Kipling alludes to this in his famous poem If:

“If you can dream, and not make dreams your master; If you can think, and not make thoughts your aim; If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster, and treat those two impostors just the same.”

Having had a dedicated meditation practice for more than 30 years, I know from direct personal experience, and hundreds of conversations with other meditators, how difficult it can be to not identify with thoughts and feelings.

In my case, I’d come from a working class family and done well at school, where my teachers had told my parents I was “very clever”.

Consequently, much of my sense of self worth had ended up being based on my thinking.

Working as an engineer, and then as a consultant to major corporations, seemingly validated this identification with my thoughts.

That’s why, when my thoughts turned in on me, they had the power to have me signed off work by the family doctor with “acute anxiety”. 12

What does it look like when someone identifies with their feelings as opposed to their thoughts?

My wife Alison and I often have fun recounting the story of when we took my sister Mary to the Orchard Tea Rooms in Grantchester, near Cambridge, famous as the home of poet Rupert Brooke, and immortalised in his poem The Old Vicarage, Grantchester (1912).

We’d chosen to go there partly for the history, partly for the ambience, and partly because the seating extends out into the orchard — ideal for refreshments after walking our dog, Sam.

It was a warm day and unfortunately we’d forgotten to take Sam’s water bowl with us.

“No problem”, I said, “I’ll just get one of the used bowls from the rack over there and fill it up from the outside tap”.

(The rack is outside the cafe, and is used by the table waiting staff to stack used crockery and cutlery before taking it inside to be washed.)

“You can’t do that..”, Alison said, “…people would be horrified if they saw a dog drinking from a bowl that people will use in future”.

“What’s the problem?” I reply. “The bowl will go through the dishwasher at 70°C before any human uses it again”.

“That’s not the point” Alison pushes back…

I often share this story with groups, and ask who agrees with me and who agrees with Alison.

A lively conversation usually ensues about why people side with each of us.

Often some people find it very hard to not identify with their thoughts or feelings about this, seeing the other perspective as stupid and/or immoral.

If, like me, they tend to identify more with their thoughts, they’ll argue based on scientific, logical argument.

If, like Alison, they tend to identify more with their feelings, they’ll argue based on what feels right or wrong as an embodied feeling.

Of course, if Alison and I hadn’t learned to reasonably separate our selves from our thoughts and feelings we would probably have ended up separating from each other... 13

The bottom line is that the more anyone identifies with their thoughts or feelings, the less open they’ll be to other perspectives, which won’t help them create future-fit cultures of innovation, agility and adaptiveness.

Nor healthy functioning personal relationships…

Personality

“I am my Personality” is is the next level below “I am my Thoughts / Feelings” in the Hierarchy of Illusions.

For a long time, psychology suggested our personality was fixed — we had a personality type, like a blood type.

That’s what the “T” stands for in the heavily debunked but nevertheless still highly popular MBTI personality test — the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator.

It’s easy to fall for the illusion that personality is the core of a person, but the origin of the word suggests differently.

Personality derives from the Latin persona — meaning “a mask, a false face, such as those of wood or clay, covering the whole head, worn by the actors in later Roman theatre”. 14

I was recently running a Zoom session with a group of senior executives and sent them off into breakout rooms with the question: “Do you ever notice your personality is different when playing different roles?”

When they came back from the breakouts, one senior executive reported rather sheepishly that in exploring this question with others, he’d realised he was very open, collegiate and collaborative in his role at work, but a bit of a tyrant with his wife and children.

He resolved to pay more attention to cultivating the persona he wanted to adopt in his home life, just as he had done over many years with the persona he adopts in his professional life.

The point being that we exhibit different personalities in different roles and contexts.

The Chairperson of a Fortune 500 company behaves differently at Board meetings than when they have their four year old granddaughter on their knee at a family gathering — hopefully…

So, if personality is an actor’s mask, what’s behind that mask?

Actor

“I am the Actor” is is the deepest level in the Hierarchy of Illusions.

Interestingly, the realisation that we’re actors playing various parts seems to be implicit in our language.

For the other levels in the Hierarchy of Illusions it feels quite natural to use the possessive: “I am my possessions”; “I am my achievements”; “I am my roles / relationships”; “I am my thoughts / feelings”; “I am my personality”.

But we don’t say: “I am my actor”.

It’s as if we implicitly understand we’re not our possessions, achievements, roles, relationships, thoughts, feelings, or personality — that these are things we have, not who we are.

But still, unless we pay attention, we all too readily fall for the illusions...

The TRAP

About twenty years ago during a seminar in Paris, I’d just gone through the above explanation whilst drawing the Hierarchy of Illusions on a flipchart.

I pointed out that reading downwards, the top four levels spells “PART” — the part the actor plays through the mask of personality.

Someone in the front row of the audience got quite animated at this point and excitedly commented, in a heavy French accent, that reading from top to bottom it indeed spells PART, but from bottom to top it “eez ze TRAP..!!!”

Ever since, whenever I talk people through the Hierarchy of Illusions I tell that story — usually adopting a very bad French accent.

But it’s not just a funny anecdote.

The comment contains an important truth.

You see, when we drift away from the awareness of “I am the actor” and ascend the hierarchy of illusions, we all to easily become trapped in identifying with our thoughts, feelings, roles, relationships, achievements and possessions — losing our selves in the process.

And because the awareness of self dictates the awareness of context, the way we see things provides salient confirmation that we are indeed the illusory self that sees things that way.

Professor John Vervaeke of the University of Toronto calls this process “reciprocal narrowing” — as our sense of self becomes narrower, our perception of reality becomes narrower, until eventually we cannot see other possibilities beyond.

He points out that reciprocal narrowing plays a central role in today’s meaning crisis. 15

Questions for reflection

At which level or levels of the hierarchy do you tend to get caught most often/deeply?

How much does your personality differ in the different roles you play?

Which roles or relationships do you find it hardest to imagine losing?

How easy or difficult are the questions above to answer?

How might observing yourself more closely and consistently help?

Title track from the 1978 album Who are you? Check out the video of the studio session filmed by Jeff Stein for the documentary “The kids are alright”

Images of Organization was first published in 1986.

I’m not saying that what we see is Made Up Mysteriously By Ourselves - which, as Dr Iain McGilchrist wryly observes conveniently spells MUMBO. But equally what we see is not a wholly independent Reality Out There - which, as he also points out, equally conveniently spells ROT. We participate actively in what we see as “other than ourself”.

This was Powell’s Rule #3 (of 13) set out in Chapter 1 of his memoir, It Worked for Me: In Life and Leadership. (Harper Collins, 2012, p9).

Marlow’s Hierarchy of Illusions is a respectful nod to, and play on, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

“All models are wrong” acknowledges that models always fall short of the complexities of reality but can still be useful nonetheless. The aphorism — and its expanded version: “All models are wrong, but some models are useful” — is generally attributed to mathematician George Box (1919 - 2013).

This is based on empirical experience with groups and individuals around the world over the past 30 years or so.

Cited in Wikipedia’s entry on Retail Therapy.

Elizabeth Gilbert “Your elusive creative genius” on TED.com

Ibid (Your elusive creative genius).

I describe this experience in the earlier Back to BASICs post (Ibid)

We’ve survived 35 years of marriage because, like all good husbands, I’ve learned to give in…🤣.

Awakening from the Meaning Crisis is the name of Vervaeke’s epic 50 episode YouTube series.