“You can't just ask customers what they want and then try to give that to them. By the time you get it built, they’ll want something new.” — Steve Jobs 1

Ever since the New England area was settled by migrants, ice from its ponds became a valuable commodity for cooling drinks and preserving food.

For generations, ice harvesting was little more than a cottage industry, where individual families, or more often their servants, would cut ice by hand in winter and store it in underground cellars for use in the summer.

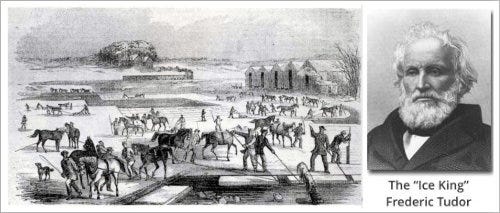

Then in the early 19th century, a Boston entrepreneur called Frederic Tudor saw the commercial potential for exporting New England ice.

Rather than going to study at Harvard, he instead set up The Tudor Ice Company, and a new industry was born: the New England Ice Cutters.

Tudor wasn’t actually the first to sell harvested ice. A tombstone inscription for a William Fletcher, born about 1770, describes him as the first person to carry “ice into Boston for merchandise.” 2

But seeing the potential to reach a much greater market, Tudor adopted a strategy familiar to entrepreneurs ever since — grow by exploiting technology, which in this case meant machinery, thermal insulation, and insulated transportation for cutting, storing, and shipping harvested ice.

Working with inventor Nathaniel Wyeth, Tudor developed steam powered saws, loading, and shipping machines that boosted efficiency, increased productivity, and drove year-on-year growth for decades. 3

Tudor used the cost advantages this generated to undercut competitors, giving away free ice to bartenders, and then charging them once their customers were hooked on cold drinks.

In 1806, Tudor shipped a cargo of ice to Martinique in the West Indies, and although he lost money on the venture, it opened a new market that would eventually become highly profitable. 4

Twenty years later, The Tudor Ice Company was shipping 12,000 tons of ice a year and Frederic Tudor had become known as “The Ice King”.

In 1833 he exported 200 tons of ice to India in a ship employing state-of-the-art Tudor/Wyeth sawdust-based thermal insulation. Half the shipment survived the 180 day voyage, and even though it sold at a net loss, The Ice King’s empire was expanding. 5

Tudor constructed above-ground ice storage facilities incorporating Tudor/Wyeth insulation. One of these, constructed in Chennai, India in 1842 still stands as a local monument to The Ice King’s ingenuity and entrepreneurship. 6

Ice from Wenham Lake, Essex County, Massachusetts was particularly admired in England for its clarity and purity, a major improvement on local ice. 7

British entrepreneurs then discovered that Norwegian ice was similar in quality to Wenham ice but available at much lower cost.

In December 1864 the newspaper Morgenbladet reported that an entrepreneur had bought Lake Oppegård and renamed it ‘Wenham Lake’ — so its ice could be sold in England as “Wenham Lake” ice. 8

Wherever there’s a market there will be con artists out to make a fast buck…

In 1857, at the age of 74, Tudor still saw a bright future and told the Boston Board of Trade that the ice harvesting industry was “yet in its infancy”. 9

He saw no reason why the strategy of the previous fifty years should not continue, as innovation in cutting, storage and shipping technologies showed no sign of slowing.

But even as he spoke, the first ice-making plants were starting up in the United States.

Blinded by past success, The Tudor Ice Company failed to see the threat that this new technology posed to their business.

The number of machine-made ice plants grew exponentially to several thousand by 1920, by which time the New England ice cutting industry had melted away… 10

The moral of the story

On one level, the story of the rise and fall of the New England ice cutters can be seen as a simple example of how disruptive innovation destroys established market leaders.

A new technology comes along that changes the basis of competition but gets dismissed, ignored, or overlooked by incumbents who are heavily invested in the legacy technologies instrumental to their past successes.

And whilst that’s a valid perspective, it's worth digging deeper into why the prolifically innovative Tudor failed to exploit machine-made ice.

The Tudor Ice Company were, after all, well set up to be pioneering adopters of refrigeration technology:

An established international customer base.

A transport and logistics network to service and potentially extend that market.

An opportunity to phase in machine-made ice gradually when and where harvested ice became less competitive.

However, the deeper reason the Tudor Ice Company failed was its awareness of being ice harvesters.

If instead they’d thought of themselves as ice producers, machine made ice would have been seen as a relevant opportunity.

But being constrained by the perception of being in the business of harvesting ice meant they couldn’t see the relevance of other ways of producing ice.

It may sound like a subtle distinction but “We are ice harvesters” as opposed to “We are ice producers” rendered Tudor blind to ice production methods that didn’t involve harvesting.

The business failed when machine made ice became a more cost effective way of providing customers with what they actually wanted — ice, not harvested ice.

The story of the New England Ice Cutters reflects the old marketing wisdom that says when customers buy 1/4 inch drill bits, they don't actually want 1/4 inch drills, what they want are 1/4 inch holes.

But if you're a drill bit producer, especially a market leading one, it’s easy to forget that seen through your customers’ eyes, you’re in the hole provision business.

Those hard won, heavily invested legacy skills in metallurgy, heat treatment, volume manufacturing, etc. make other potential hole-producing technologies such as punches, lasers, high-pressure water jets etc. seem irrelevant — even though all are potential alternative ways of giving customers what they actually want.

The Tudor story doesn’t end with the realisation that customers want ice as opposed to harvested ice. What customers actually wanted wasn’t ice per se but a way to cool drinks and food.

That’s why, as we know looking back more than a century later, home refrigeration is a highly relevant technology, with domestic fridges eventually replacing machine made ice, and the associated ‘ice boxes’ in which it was kept.

Customers didn’t even want ice. What they actually wanted was cold.

Or did they?

What many customers actually wanted was food preservation.

Today we buy foodstuffs such as long-life UHT milk, soups, sauces, soya, oat, and nut-based drinks in aseptic packaging — a technology that competes with refrigeration as a means of food preservation. 11

And aseptic packaging manufacturers will in turn end up being disrupted if they fail to keep up with what their customers are actually buying as this continues to evolv.

The history of human enterprise is full of examples of organisations that failed to see what business they were actually in.

A few of my other favourite examples of organisations who were either slow on the uptake or failed to keep up with their customers include:

Black & Decker — who rejected Ron Hickman's collapsible workbench idea that became the “Workmate”. This was a big hit with users for holding work steady, but because they saw themselves as a power tool company B&D couldn't see the Workmate’s relevance as it had no motor. They only eventually acquired the rights after Hickman had successfully launched the product himself.

Kodak — world leaders in mass-market photography for over a century, were far too slow making the shift to the very digital technologies that allowed people to actually achieve their motto “share moments, share life”. 12

Xerox — who, despite investing hugely in technology for the paperless office, and inventing many of the technologies used in the personal computer, smartphones and tablets, failed to commercialise them. 13

Procter & Gamble — who threatened to fire Vic Mills, the internal champion of the “silly disposable diaper project” that became market leading Pampers. P&G saw themselves as a soap company and a disposable diaper not only didn’t sell soap, it might even reduce sales of soap for washing cloth diapers…

All the above organisations knew what they were selling, but didn’t see what their customers were actually buying.

Someone who understands this challenge well is April Dunford, a market positioning advisor to B2B tech companies:

“One of the most important yet misunderstood concepts in marketing is value. And not just value but differentiated value. I think differentiated value is really hard for technology companies, in particular, to get right.

In tech, we are very, very comfortable with features and capabilities. We are super excited about our new advanced machine learning, next-generation analytics, optimized storage, etc., and we often assume our audience understands the value of those capabilities. But quite often, we are dead wrong.

There are two key things we need to keep in mind across marketing and sales when it comes to value.

Firstly - we overestimate the buyer’s ability to translate features to value for the business.

In B2B, frequently, the person we are selling to has never purchased a product like ours before. They may be users of a competing solution today, but that doesn’t mean they understand the underlying technology and why they should care about those capabilities. It’s our job to do that translation from features to value for them. You have advanced machine learning capabilities - so what? What does that capability enable for the customer's business? Customers are experts in pain - we are experts in solutions.Secondly, we can't forget that value alone doesn’t win deals — differentiated value does.

If every alternative on the market delivers on a particular point of value, that value becomes unimportant in a purchase decision. Your CRM makes it easy to track a deal. So do all of the other CRMs on the market. Your accounting system makes it easy to file taxes - the others do too. We are frequently positioning and selling as if the question we need to answer is “Why choose us?” But the real question is “Why choose us over the alternatives?”

Our differentiated value is what we can do for a customer’s business that no other alternative solution can. It is the reason a certain type of customer should choose us over any other alternative. Our positioning, messaging, and sales narrative need to be firmly oriented around our differentiated value if we want to make it clear to customers why they should pick us.” 14

Questions for reflection

Which technologies that were central to your own organisation’s success in the past might now be preventing it from creating its future?

Does your organisation understand its customers well enough to understand your differentiated value and to pick up early signs of shifts in what they actually want?

What are your customers actually buying from you?

Are you sure?

“Crystal Blocks of Yankee Coldness — The Development of the Massachusetts Ice Trade from Frederic Tudor to Wenham Lake 1806-1886” by Philip Chadwick Foster Smith from

The Essex Institute Historical Collections, 1961

“Melting Markets: The Rise and Decline of the Anglo-Norwegian Ice Trade, 1850-1920” — by Bodil Bjerkvik Blain, LSE — p6.

“Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation: How Companies Can Seize Opportunities in the Face of Technological Change” — James M. Utterback — p 146.

Ibid Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation — p 146.

Ibid Melting Markets —p 6.

Ibid Melting Markets —p 9.

Ibid Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation — p 151.

Ibid Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation — p 157.

Like many corporate mottos, Kodak’s was more ad agency PR slogan.

To be fair, Xerox did invent laser printers - by taking the back end of a Xerox 7000 photocopier and replacing the front end imaging mechanism with a scanning laser - an adaptive, rather than disruptive, innovation.