Leadership DRAMA

Are senior executives capable of creating long term futures for their organisations?

“Leadership is the capacity of a human community to shape its future”. — Dr Peter Senge 1

Where is your organisation headed?

I don’t mean in the theoretical, rose-tinted spectacles, “PR-spin concocted for investors, customers, and new hires” sense of: “what does your organisation say in its vision, mission, or purpose statement?”

I mean in the real, practical, cold light of day sense of: “what destination is your organisation actually headed towards as a consequence of the embedded attitudes, behaviours, actions, and interactions that dictate its long term future?”

Destination

Just as the bed of a river directs where its waters flow, if the mindsets, attitudes, and behaviours that dictate actions and interactions remain the same, we’ll continue in the direction we’re currently headed.

Is the current destination — of our organisations, society, planet, and ourselves as individuals — really where want to end up..?

If, as Peter Senge suggests, “Leadership is the capacity of a human community to shape its future”, then it’s how we enacted this in the past — how we previously developed and deployed our community capacity — that shaped the future we’re living in today.

The world we’ve created for ourselves as a human community was shaped by how we enacted sense making, decision making, and action taking in the past.

Given the shape our organisations, society, and the world in general is in, we’ve clearly not done a stellar job...

So it’s high time we did something different.

If we keep doing what we’ve been doing, we’ll get more of what we’ve been getting.

And if we keep thinking in the ways we’ve been thinking, we’ll keep doing what we’ve been doing.

If we want to improve our destination, we need to improve our thinking, actions, and results — not just amplify and accelerate the habits of the past by bolting AI on top…

Results

The longer term destination of our organisations, society, and the world at large, are all dictated by the net effect of the short and medium term results we create along the way.

For most of organisational history, senior executives — CEOs especially — were rewarded for quarterly financial results.

Over the past few decades, to extend their focus further into the future, senior executive remuneration was increasingly geared to longer term metrics, typically linked to market share and stock price.

But advised by big consulting firms, senior executives found ways to game the system, using tricks like share buybacks to manipulate stock prices that helped boost their remuneration, often at the expense of longer term organisational health.

Those who cultivated the technical and administrative skills to excel at the financial numbers game came out “the winners”.

But times have changed.

So much so that even that most traditional of institutions, Harvard Business School, has begun to notice: 2

“For a long time, whenever companies wanted to hire a CEO or another key executive, they knew what to look for: somebody with technical expertise, superior administrative skills, and a track record of successfully managing financial resources.

When courting outside candidates to fill those roles, they often favored executives from companies such as GE, IBM, and P&G and from professional services giants such as McKinsey and Deloitte, which had a reputation for cultivating those skills in their managers.

That practice now feels like ancient history.

So much has changed during the past two decades that companies can no longer assume that leaders with traditional managerial pedigrees will succeed in the C-suite.” 3

The above quote is from an article in the July-August 2022 issue of HBR written by HBS scholars working with executive search firm Russell Reynolds — the latter having given the former access to around 5,000 job descriptions, revealing a major shift in the selection criteria for senior executive hires from 2000-2017.

The HBS/Reynolds article continues:

“Over the past two decades, companies have significantly redefined the roles of C-suite executives. The traditional capabilities mentioned earlier—notably the management of financial and operational resources—remain highly relevant.

But when companies today search for top leaders, especially new CEOs, they attribute less importance to those capabilities than they used to and instead prioritize one qualification above all others: strong social skills.

When we refer to “social skills,” we mean certain specific capabilities, including a high level of self-awareness, the ability to listen and communicate well, a facility for working with different types of people and groups, and what psychologists call ‘theory of mind’—the capacity to infer how others are thinking and feeling.

The magnitude of the shift in recent years toward these capabilities is most significant for CEOs but also pronounced for the four other C-suite roles we studied.” 4

The research recognised that more IT doesn’t help, but actually drives the need for greater human-centric skills:

“Increasingly, in every part of the organization, when companies automate routine tasks, their competitiveness hinges on capabilities that computer systems simply don’t have—things such as judgment, creativity, and perception”. 5

An organisation’s long term destination depends on the cumulative effect of short and medium term results created through the attitudes, behaviours, actions and interactions of people in every part of the organisation.

As the HBS/Reynolds article highlights, senior executives need the requisite skills to create conditions that cultivate judgement, creativity, and perception in every part of the organisation.

Actions

How can senior executives cultivate the skills their organisations need to take effective action to generate short and medium term results that lead to a better destination?

I’ve previously highlighted the work of cognitive scientist and University of Toronto Professor John Vervaeke, and his observation that in today’s world we focus almost exclusively on the most superficial level of knowledge — what cognitive science refers to as propositional knowledge. 6

Propositional knowing results in beliefs, which we organise into theories of how things are, creating a felt sense of conviction that our knowledge is true.

This is what schools, colleges, universities, and business schools focus on teaching — facts we can retrieve and assert with conviction, much like a computer.

But as the HBS/Reynolds study confirms, future organisational success “hinges on capabilities that computer simply don’t have—things such as judgment, creativity, and perception”. 7

But it’s not enough to know, propositionally, what future skills senior executives need, having acquired new beliefs and theories by reading an HBR article, however compelling.

We actually need to cultivate those skills so senior executives change their attitudes, behaviours, actions, and interactions.

Vervaeke points out that this requires deeper ways of knowing, that cognitive science calls procedural, perspectival, and participatory knowledge: 8

“I have to know how to adaptively seek for relevant information from the environment. My propositional knowledge is actually dependent on my knowing how to do many things.

This is called procedural knowledge — knowing how to do something. And the content of procedural knowing is not a fact, it's a sensorimotor interaction with the world.

Procedural knowing doesn't result in belief, in theory, it results in skills. And when those skills are developed well so that they have reliable applicability then what we have is expertise. 9

In plain language, the cognitive science term sensorimotor means iterative sense making, decision making, and action taking.

Iterative sense making, decision making, and action taking undertaken by an individual results in skills that, reliably applied over time, gives them expertise.

However, as the HBS/Reynolds research points out, these skills are not just needed in a few people, they’re needed “increasingly in every part of the organisation”.

When sense making, decision making, and action taking are undertaken collectively — tightly coupled, rapidly & repeatedly iterated, deeply embedded, widely distributed, consistently throughout an organisation, the result is a future-fit culture of innovation, agility and adaptiveness.

How to make that happen?

Mindsets

The “strong social skills” the HBS/Reynolds article highlight in future senior executives — self-awareness, listening and communicating, working with diverse people and groups, inferring thoughts and feelings — arise naturally when individuals adopt 2D3D mindsets.

The power of mindsets is well illustrated by Donella Meadows’ seminal 1999 paper: Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System.

The second highest leverage point for transformational change is the mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises, only surpassed in its change leverage by the power to transcend paradigms. 10

Meadows describes this as follows:

“Whether it was Copernicus and Kepler showing that the earth is not the center of the universe, or Einstein hypothesizing that matter and energy are interchangeable, or Adam Smith postulating that the selfish actions of individual players in markets wonderfully accumulate to the common good, people who have managed to intervene in systems at the level of paradigm have hit a leverage point that totally transforms systems.

You could say paradigms are harder to change than anything else about a system, and therefore this item should be lowest on the list, not second-to-highest.

But there’s nothing physical or expensive or even slow in the process of paradigm change.

In a single individual it can happen in a millisecond.

All it takes is a click in the mind, a falling of scales from eyes, a new way of seeing.” 11

Individuals with 2D3D mindsets develop a new way of seeing.

They understand, experientially, that each of us comes at things from our own angle, bringing with us our unique, individual, diverse, but inevitably partial perspectives.

They’re curious to discover the diverse perspectives of others, recognising no-one ever sees the whole picture. 12

The future-fit cultures that organisations need, if they’re to thrive in an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world, rest on a foundation of such 2D3D mindsets.

However, influential individuals who fail to develop a 2D3D mindset and instead mistake their 2D perspective for the whole picture, are the biggest human barrier to creating a future-fit culture.

Unfortunately, many senior executives whose awareness is deeply invested in their technical expertise, administrative, and financial skills fall into this trap.

That’s why they lack the “strong social skills” cited in the HBS/Reynolds article.

Awareness

The HBS/Reynolds article describes the typical awareness of traditional senior executives — someone who feels most at home dealing with technical, administrative, and financial matters.

They highlight this as the awareness of the senior executive role typified in firms like GE, IBM, P&G, Deloitte, and McKinsey but which “no longer leads to success in the C-suite.”

Why does awareness matter so much?

Because it affects how we perceive the world, and the skills we develop to succeed in that world. 13

For most of organisational history, senior executives were encouraged to adopt the awareness that their #1 job was to make decisions.

The successful senior executives of the future will be those who adopt the awareness that their #1 job is to create conditions in which good decisions get made and implemented — through ongoing, iterative sense making, decision making and action taking, embodied, embedded, and enacted throughout the whole organisation. 14

Leadership DRAMA

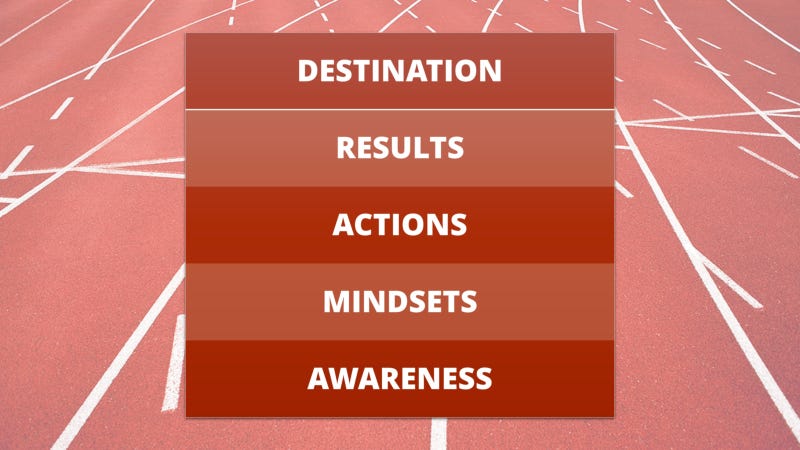

An organisation’s Destination depends on the Results it creates, which depend on the Actions people take which depend on their Mindsets which depend on their Awareness.

Up until 40 years ago, organisations and the senior executives who ran them, focused on Results and the Actions needed to achieve them — with precious little attention paid to Destination, or Mindsets and Awareness.

In the 1980s, organisations — advised by big consulting firms — made their first faltering attempts to influence Mindsets and Awareness, by articulating their supposedly shared values. 15

In the 1990s, organisations — again advised by big consulting firms — attempted to create a sense of organisational Destination with vision and mission statements.

More recently, organisations — yet again advised by big consulting firms — had another stab at influencing Mindsets and Awareness, this time by articulating an organisational purpose.

All of these attempts have failed to move the needle because they failed to build new muscles inside the organisation.

For that muscle building to occur, the heavy lifting of developing new ways of working must be done by people inside the organisation — not armies of junior consultants shipped in from outside.

The only people who build any muscles that way are the consultants.

That’s why past organisational efforts to influence Destination, Mindsets, or Awareness have ended up as glorified PR exercises with no lasting positive influence on the day-to-day experience of organisational life.

Senior executives, guided by advice from big consulting, learned to talk a good game in their marketing brochures, advertising slogans, and annual reports.

However, as the HBS/Reynolds article shows, neither group possessed the skills required to create genuinely future-fit cultures.

If current senior executives fail to develop the skills to guide their own people to build the requisite organisational muscles, they’ll end up being replaced by others who can.

Old school leadership is unravelling, and the real leadership DRAMA is beginning to unfold…

Questions for reflection

How well does your organisation balance short term results with a deep understanding of the longer term destination it’s currently headed towards, due to the baked-in attitudes, behaviours, actions, and interactions directing its future?

What destination is your organisation, and your career, headed towards?

What’s currently being done in your organisations to create a culture that’s fit for an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable future?

The Dance of Change (1999) p 16.

A recent article The Boats in Boston Harbor describes how business schools like Harvard have unintentionally perpetuated fads that failed to create future-fit organisations.

HBR July-August 2022 “The C-Suite Skills That Matter Most”

Ibid — HBR/Reynolds C-Suite Skills article. The “other four” C-suite roles Russel Reynolds gave HBS data on were CIOs, CFOs, CHROs and Chief Marketing Officers.

Ibid — HBR/Reynolds C-Suite Skills article.

I’ve touched on Vervaeke’s work in several recent articles including The Boats in Boston Harbor (Ibid), The Hierarchy of Illusions and Future-fit you.

Ibid — HBR/Reynolds C-Suite Skills article.

I described these four ways of knowing in The Boats in Boston Harbor (Ibid)

From Vervaeke’s talk at the 2020 Embodied Movement Summit at 21:45 — 22:30 in the YouTube recording here.

Ibid — Meadows’ Leverage Points.

For more on the 2D3D mindset, see this previous article.

I described this effect in detail in a previous piece Back to BASICs

I’ve written more about this in a previous article Senior Executives Must Give Up their Decision Rights.

Unfortunately, this was simply plucked out of thin air by McKinsey, as described in this previous piece The Toxic Myth of Culture as Shared Values.