Influential Thinkers: Peter Senge

Learning organisations are human communities

“Leadership is the capacity of a human community to shape its future.” — Peter Senge 1

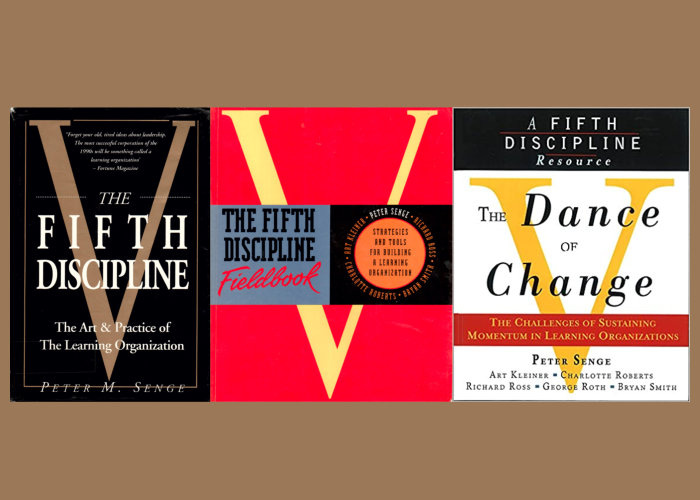

Peter Senge became a high-profile figure in the organisational learning movement following publication of his book The Fifth Discipline in 1990.2

Harvard Business Review called it one of the seminal management books of the previous 75 years and to date it has sold more than 2.5 million copies.3

Although organisational learning had been written about since the 1970’s, notably by Chris Argyris and Donald Schön, Senge’s success reflected a more receptive market for such ideas combined with his well-balanced and highly readable writing style. 4

Senge’s book was well positioned — sitting neatly between at one extreme the typical incomprehensibility of academic writing, and at the other extreme the dumbed-down, overly simplistic, one-size-fits-all, paint-by-numbers, cookie-cutter approaches proliferated by mainstream Big Con management consulting firms.5

[The main reason organisational learning never fulfilled its potential is that it requires culture change that can only be achieved when people inside organisations do the heavy lifting for themselves, by themselves — which threatens the existence of the Big Con firms.] 6

As you can imagine, the huge success of the book and Senge’s heightened profile generated significant pushback from individuals in both the academic and one-size-fits-all communities — some of which continues more than 30 years on…

Organisational learning also drew attention away from another hitherto burgeoning field — knowledge management — heavily promoted at the time by IT companies as a way of supposedly capturing, storing, and retrieving institutional knowledge that would otherwise be lost as employees retired.

Unfortunately, the “knowledge” that can be programmed into IT systems excludes the vital tacit, embodied knowledge that’s of real value to organisations — which is inherently addressed more effectively by focusing on organisational learning instead. 7

I read The Fifth Discipline when it first came out, and found that much of it resonated with my own experience helping organisations create cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness. 8

The five disciplines of the book’s title are:

Personal Mastery — which “goes beyond competence and skills, though it is grounded in competence and skills. It goes beyond spiritual unfolding or opening, although it requires spiritual growth. It means approaching one’s life as a creative work, living life from a creative as opposed to reactive viewpoint.” 9

Mental Models — which recognises that “new insights fail to get put into practice because they conflict with deeply held internal images of how the world works”. 10

Shared Vision — “Just as personal visions are pictures or images people carry in their heads and hearts, so too are shared visions pictures that people throughout an organization carry”. 11

Team Learning — “is the process of aligning and developing the capacities of a team to create the results its members truly desire”. 12

Systems Thinking — the fifth and integrating discipline. “The bottom line of systems thinking is leverage — seeing where actions and changes in structures can lead to significant, enduring improvements”. 13

Senge describes how the above disciplines help address seven learning disabilities that commonly afflict organisations: 14

“I am my position”. When people adopt and assign identities based on organisational roles they fail to see how localised sense making, decision making, and action taking adversely impacts the organisational community as a whole. 15

“The enemy is out there”. A form of attribution bias where people protect their adopted identities by assigning blame elsewhere, thereby failing to see how they themselves contribute to the problems they encounter.

“The illusion of taking charge”. All too often, proactiveness is reactiveness in disguise. We feel a powerful need to do something. Action X is something. So we feel compelled to do Action X. 16

“The fixation on events”. When we see life as a series of events, each with a single cause, we default to reductionist thinking and fail to see the deeper systemic forces at play.

“The Parable of the Boiled Frog”. People adapt over time and are more likely to don wellington boots to wade through organisational crap when what’s really needed is — as my friend Colin Newlyn eloquently puts it — to decrapify work.17

“The delusion of learning from experience”. This type of learning is all well and good when the effects of our actions are encountered immediately. But much of what happens in organisations is deeply systemic, with outcomes resulting from complex combinations of multiple factors that take months or years to show up.

“The myth of the management team”. Such teams often function adequately when addressing routine issues. However, when facing novel challenges they frequently exhibit skilled incompetence — team participants are proficient at preventing themselves and their organisations from learning. 18

My connections

With colleagues Joel Janowitz and Charlie Kiefer, Senge set up the organisational learning advisory firm Innovation Associates (IA) to help organisations create and sustain learning cultures.

In 1994, Senge et al published a field guide to creating learning organisations: The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook. 19

A year later, in 1995, IA was acquired by Arthur D. Little (ADL) who, at the time, also owned the open innovation lab where I’d been working since 1983.20

With the IA acquisition, I joined the combined ADL/IA practice and over the next six years had the fortune of working with IA colleagues at the leading edge of key aspects of organisational learning, including Joan Lancourt.21

Senge remained at MIT and established the Organizational Learning Centre (OLC), which eventually span out of MIT as the Society for Organizational Learning (SoL).

I then worked with Peter on the Global Leadership Team of SoL from 2009-2015.

In 1999, Senge et al published the third book in the Fifth Discipline series, The Dance of Change, which introduced his deeply insightful definition that “leadership is the capacity of a human community to shape its future”. 22

When I met up with Peter in April 2022 I realised I’d never asked him how he’d arrived at that definition — so I did. His answer was “It just seemed obvious”. 23

At the time, I was a bit disappointed by this response, but a few months later the penny dropped that his answer simply reflected the worldview Peter has inhabited ever since I met him — organisations as human communities.

This is in stark contrast to traditional worldviews that tend to be built on a mix of four legacy metaphors: organisations as machines, armies, politics, and teams. 24

These legacy ideas led to the prevailing leadership orthodoxy, captured in this still dominant definition by retired Harvard Professor John Kotter:

“Leadership defines what the future should look like, aligns people with that vision, and inspires them to make it happen”. 25

In this legacy perspective, an elite cadre of people “define a future vision” and “align” and “inspire” others to “make it happen”. The defining/aligning/inspiring is done by this elite — the “leaders” — and is done to everyone else — the “followers”.

Senge’s view that “Leadership is the capacity of a human community to shape its future” doesn’t segregate people into those who do leadership and those who have it done to them. Instead of creating followers, this develops more leaders — or rather unleashes the organisational leadership required to create and sustain a future-fit culture.

Kotter did eventually acknowledge the failing of this legacy worldview 13 years later, noting in his book’s 2012 reprint: “more agility and change-friendly organisations” and “more leadership from more people, and not just top management” are increasingly vital. 26

This definition appears in The Dance of Change (Senge et al 1999) p16 The Dance of Change was the third book in The Fifth Discipline series

The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization on Goodreads. I had the fortune of working with Peter Senge on the Global Leadership Team of the Society for Organisational Learning (SoL) from 2009—2015. I also served as a Board Director for the UK Chapter of SoL along with another Influential Thinker — Arie de Geus.

For example see this Chris Atgyris article from HBR September 1977.

For more on the Big Con see How management consulting went rogue.

For more on this topic, download my free 22-page Five Fatal Habits report.

For more on these different types of knowledge see this previous article.

The work I’ve specialised in since the late 1980’s is helping organisations (throughout Europe, Asia, and the USA) create future-fit cultures.

Ibid The Fifth Discipline — p141 in my copy from 1990.

Ibid The Fifth Discipline — p174. I personally find Mindsets a more useful framing than Mental Models because it highlights greater leverage for change at the Being and Seeing levels. For more on this, see the previous article: Demystifying Mindsets.

Ibid The Fifth Discipline — p206. Back in 1990 the world still seemed sufficiently certain and predictable to consider Shared Vision as “WHAT do we want to create together?”. In today’s increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world it’s much more relevant and useful to think of Shared Vision in terms of “HOW do we want to work together to create continuous new value?”

Ibid The Fifth Discipline — p236.

Two key points to note here: 1) “Structure” doesn’t just mean what’s visible on the surface but the deeper, more subtle structure “below the waterline” in the often used iceberg analogy; and 2) Systems Thinking is more than just Systems Dynamics.

Ibid The Fifth Discipline — p18-25

For more on adopting and assigning identities, see this previous article.

Colin on LinkedIn. His excellent Decrapify Work Substack channel is here.

Skilled incompetence by Chris Argyris in HBR September 1986.

The open innovation lab Cambridge Consultants — “A future unconstrained by current thinking”.

Joan Lancourt is another important thinker I’ve written about previously.

Ibid The Dance of Change page 16.

Peter and I caught up when he delivered the annual Mike Jackson lecture at the Centre for Systems Studies at Hull University, UK in April 2022.

For more on these metaphors, see this previous article.

Leading Change (1996). This definition is on page 28 in the revised edition published in 2012.

Ibid (Kotter 2012, preface page ‘ix’).