Influential Thinkers: Peter Scott-Morgan

One of the most effective practitioners of real-world culture change in organisations

“Maybe 10 years ago we should have come down from the clouds and looked inside ourselves to think what was actually driving our own behaviour, rather than come up with grandiose constructs relating to culture.

If only we had, we would have found that there was indeed a more pragmatic, leaner way to come to grips with behavioural barriers to effective change. We would have understood that most of the time, charting corporate culture is not even necessary. What is more, we would have realised that we knew the key insight all along.

It is the secret that everyone already knows.” — Peter Scott-Morgan, The Unwritten Rule of the Game. 1

Peter Scott-Morgan was a prolific generator of insights and practical approaches to transformational culture change in real world organisations.

He had a significant impact on my career in many ways — only a few of which I can highlight here, or this article would end up replicating his three books... 2

Peter and I first met in the mid 1980’s when we both worked for the open innovation lab Cambridge Consultants.3

We then subsequently worked for the lab’s parent company, the management consulting firm Arthur D. Little (ADL).

In the late 1980’s, Peter’s professional focus moved away from his original PhD work in robotics, shifting instead to helping corporate clients uncover the deeper drivers of organisational behaviour, and overcome the hidden barriers to culture change.

He made the move to ADL a few years before me, having seen how recommendations provided by mainstream consulting firms were “intellectually neat but rarely worked in the real world”, and decided to do something about it.4

Alongside Peter’s move into culture change work, I’d noticed that one of the often overlooked benefits our technologists, scientists, and engineers brought to clients of the open innovation lab was how we got people in their organisations working better across their own internal boundaries, unlocking more of their own capacity for future innovation, agility, and adaptiveness.

I was also actively helping client organisations develop this internal capacity — ever since a long-standing client of the lab asked me: “Could you come and make our people behave more like your people..?”

Given the similarities in our work, Peter asked me to review the pre-publication draft of The Unwritten Rules of the Game and we subsequently worked closely together until he eventually retired from professional practice in 2007.5

The Unwritten Rules of the Game

The first of Peter’s three books, The Unwritten Rules of the Game, was McGraw-Hill’s Business Book of the Year in 1994.

Its central message was that even though the actions, interactions, attitudes and behaviours of people in organisations often seem strange, surprising, or downright bizarre, they’re always driven by a compelling, underlying but often hidden logic.

This hidden logic, and the unwritten rules that stem from it, are central to the system of mindsets that constitute an organisation’s culture by forming and informing people’s awareness of “the way we do things round here”. 6

A useful way of thinking of the unwritten rules is “the advice you’d give a close friend on how to survive and thrive in the organisation”.

These rules, Peter saw, are driven by three factors, which he termed “Motivators”, “Enablers” and “Triggers”.

Motivators

These are the things people want from their work — for example career advancement, interesting work, international travel, more money, client exposure, etc.

Enablers

These are the people, not necessarily in the most senior positions, who actually influence whether individuals get access to what they do want from their work and whether they are denied access — ending up obliged to do things they don’t want.

Triggers

These are the outcomes, attitudes, and behaviours individuals infer the Enablers want to see if they’re to grant access to the Motivators and, conversely, what the Enablers don’t want to see or they’ll likely deny access to the Motivators.

Motivators tend to be hard to shift because they are what people want. People do of course change in what they want, but it’s challenging — and arguably ethically dubious — to get them to do so.

Enabler networks are easier to change, which is why so many organisational change initiatives intuitively go down the restructuring route — albeit often with poorly thought-through, ultimately predictable, unintended adverse side-effects.

Triggers are the easiest to change — for example one organisation changed its culture quickly by revising its promotion criteria from “18 months hitting your numbers” to “five years creating sustained success with colleagues who consistently value your contribution”.

A central reason for the consistent failure of the one-size-fits-all, cookie-cutter, so-called “best practice” culture change methodologies of mainstream management consulting firms is they hardly ever identify the real Enablers — the key influencers whose mindsets, and therefore attitudes and behaviours, systemically affect everyone and everything else.

The counterintuitive fact that actual key influencers don’t necessarily occupy the most senior positions is often overlooked — a fatal mistake that continues to derail otherwise seemingly-sensible culture change interventions to this day. 7

Peter and I shared a deep interest in Systems Thinking, mine from my background in real-time control systems, and Peter’s from his PhD in robotics.

“How do you tell a systems thinker from a linear thinker?” Peter would often ask — and then present the following scenario: “You have a robot arm for lifting heavy objects in a factory, but the arm bends under loading — how do you solve this problem?”.

The linear thinker’s solution is usually to weld more metal onto the arm, to stiffen it up so it doesn’t bend. But a heavier arm requires more power, and its greater inertia makes its movements slower, reducing agility, throughput, and productivity.

The systems thinker’s more elegant solution is to allow the arm to bend, so long as it doesn’t exceed its elastic limit, and compensate for the bending by tweaking the feedback dynamics in the robot arm control system.

It’s an example that has powerful parallels in organisational leadership.

Linear thinkers in executive roles invariably seek to impose written rules on others in an effort to shore up their perception of being “in control” — written rules that naturally enough get “reinterpreted” into the unwritten rules that actually govern behaviour.

By contrast, systems thinkers in executive roles happily accept deviation so long as things remain in overall control. They don’t need things to be in their control.

Unfortunately, very few executive role holders exhibit systems thinking... 8

The Accelerating Organisation

Peter’s second book was The Accelerating Organisation (1997). 9

Amongst other insights, this featured the Five Questions of Change — the sequence individuals go through when expected to buy in to proposed organisational change.10

Question 1 — "Why Change?"

The first question someone asks themselves when called upon to change is “Why change?” What’s wrong with things as they are? If the individual doesn’t get a convincing answer to this question, they won’t change. They may pretend to change and go through the motions of change — at least when those championing the change are watching. But in the end, they’ll either ignore or undermine the change.

Question 2 — "Why this change?"

Once someone has a satisfactory answer to “Why change?”, they then want know why this change in particular? What other options have been considered? They may see other options that appear preferable. They may regard the proposed change as self-serving for its proponents. So, even though they accept the need for change, if they don’t accept the need for this change, they’ll again either ignore or undermine it.

Question 3 — "Do I want to be part of this change?"

Assuming they agree with the proposed change as both necessary and appropriate, they next consider if it’s right for them personally. They may take the view that “If this is the future here, then I’m off somewhere else”. Of course, it may not be so easy to go elsewhere, so instead they remain present physically, but check out mentally.

Question 4 — "Do I have what it takes to succeed in the future organisation?".

Assuming they see the change as necessary, appropriate, and want to stick around, the next question is how will they fare in the proposed future organisation? They may respond positively: “I can learn new skills. I can grow. I can develop” or they may feel “I’m not sure I can adapt successfully. Others seem more likely to succeed and may overtake, displace, or replace me”. So, despite navigating the preceding questions, the person who doubts their ability to survive and thrive in the future still won’t support the change.

Question 5 — "Are the tangible and intangible rewards aligned with this change?".

People often assume that money is the main — or the only — reward that matters to people at work. In practice, intangible rewards are often much stronger motivators — for example a sense of achievement, recognition, interesting work, meaningful career opportunities, etc. Where money is important, it’s often because it acts as a proxy for perceived value to the organisation — especially if feedback on more intangible aspects is limited, unclear, or badly communicated.

It’s important to recognise that in practice, only a few people sail through all five questions — the people who’ve designed and seek to impose the change...

Everyone else gets stuck: some at Question 1, some at Question 2, some at Question 3, some at Question 4, and some at Question 5.

Note that people progress more readily through the five questions when they are involved in ongoing sense making and decision making, not just action taking. This becomes even more crucial when creating future-fit cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness in which sense making, decision making, and action taking must become ever more tightly coupled, rapidly and repeatedly iterated, deeply embedded, and widely distributed throughout the organisation. 11

The End of Change

Peter’s third book was titled The End of Change (2001).12

Co-authored with colleagues from ADL’s Rotterdam office, it addresses a challenge that still persists. In fact the book could easily have been written today, almost a quarter century later, as its summary describes:

“Corporate leaders find themselves on the horns of a dilemma. Their companies need to change faster and faster, yet their employees’ energy for change is becoming exhausted. As employees suffer from change fatigue and yearn for less disruption, executives are driving for ever-greater change”. 13

The book identifies the basic underlying problem is that organisations approach “change” as a sequence of steps, classically “unfreeze — change — refreeze”, an approach frequently, but falsely, attributed to the brilliant Kurt Lewin. 14

The appropriate course of action, the book argues, is:

“Innovative companies should not fixate on change; they should concentrate on maximizing stability, with the innovation built in. To thrive within turbulence, an organization has to maximize what we call “stable innovation”. This takes different forms in different circumstances”. 15

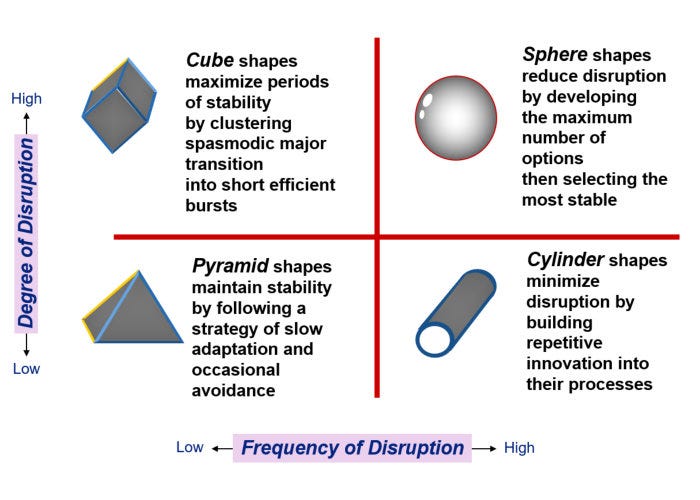

The book describes these “different forms in different circumstances” using the metaphor of four physical shapes, each representing the quadrants of a two-by-two matrix with axes “Degree of Disruption” and “Frequency of Disruption” as follows: 16

Pyramids

“Pyramids maintain stability in an environment of incremental innovation, following a strategy of slow adaptation and occasional avoidance. A pyramid is the most difficult structure to move. It sits solidly on its broad base and is difficult to rock. The only way to move it is by nudging it along, but there’s a lot of resistance. It’s hard, perhaps impossible, to move it very far very fast.” 17

Cubes

“Cubes maximize periods of stability by clustering spasmodic innovation into short, efficient bursts. The cube is also stable, firmly on its base. To move it you push in just the right place and get it to pivot on its edge. Keep applying the pressure and it will roll over into a new position. To move it more, you need to apply pressure once again, pivot it up, and keep pushing until it rolls over.” 18

Cylinders

“Cylinders minimise disruption by building repetitive innovation into their processes. The cylinder is easy to move, so long as it’s rolling on its long axis. Try pushing the cylinder in any other direction and it’s nearly as difficult as shoving at a Pyramid or Cube. Once the cylinder is rolling, you can gently steer it — but only gradually.” 19

Spheres

“Spheres reduce disruption amid incessant innovation by developing the maximum number of options, then selecting the most stable. The sphere, of course, is relatively easy to move in any direction and can be steered as it is rolled. Change the direction as often as you like. Compared with the other structures, it’s highly mobile. Yet, like the other structures, the Sphere cannot be moved up and down — so it's not fully mobile.” 20

Some organisations — the book cites examples of The World Bank or an oil refinery — largely behave as Pyramids.

The Apollo space program or a national army tend to be more Cube like in their ways of maintaining stability.

A fashion house such as Calvin Klein or a chip maker like Intel tend towards Cylinder — geared for 6-month and 18-month new product launch cycles respectively.

Innovation labs like Cambridge Consultants and disaster response organisations tend towards the Sphere.

The book points out that it would, however, be overly simplistic to categorize an entire organization as a single stability structure.

While an organisation may have one dominant structure, most have a portfolio of different structures: for example finance and legal departments in almost any company are nearly always Pyramidal, R&D functions tend to be Cylinders, innovation labs Spheres, etc.

The central theme of The End of Change is that each organisation needs to develop the right portfolio of structural elements if it is to sustain high performance and foster innovation with a minimum of disruption.

Ultimately, disruption is felt by people, so to minimise those feelings the organisation must structure itself to address the underlying drivers of these perceptions.

Questions for Reflection

What are some of the main unwritten rules preventing your organisation from becoming future-fit?

Where have you seen people get stuck along the five questions of change? At which of the questions have you personally experienced yourself being stuck in the past?

Does your organisation feel like it has the right portfolio of shapes, or — like so many others in today’s increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world — is there too much Pyramid and Cube, and not enough Cylinder and Sphere?

The Unwritten Rules of the Game — p16. For more on this, see the previous article: The secret everyone already knows.

Peter’s three books: The Unwritten Rules of the Game (1994), The Accelerating Organization (1997), The End of Change (2001) — links below.

I joined Cambridge Consultants in 1983 as a digital systems engineer, ran various technology projects, and led the Digital Systems Group before moving into consulting. Peter was one of two new hires in the mid-1980s, tasked with developing CCL’s presence in the emerging Computer Integrated Manufacturing market — the pair being dubbed “The Dynamic Duo”. In typical CCL style, this name not only alluded to Batman and Robin, but reflected the irony that the name of Peter’s then more senior “Batman” was actually Robin...

Sadly, in late 2017 Peter was diagnosed with the aggressive ALS form of Motor Neurone Diseases (MND), passing away in June 2022 due to its progression.

This theme evolved in my own subsequent work, eventually crystallising into the insight that an organisation’s culture is the system of mindsets forming and informing people’s awareness of “the way we do things round here”. For more detail, see this previous article.

For more on this topic, see the previous article Focus on key influencers.

This is an issue my colleague Paul Barnett seeks to address with Dr Mike Jackson OBE, author of Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity. Find out more here.

Peter co-authored The Accelerating Organisation with senior ADL colleague Arun Maira.

Ibid The Accelerating Organisation p45.

End of Change on Google books.

Ibid — End of Change (preface page xi).

Cummings, Bridgman, and Brown explored Lewin’s work in detail, showing that he never wrote about “change as three steps” (CATS). Despite this, if you Google “Lewin change as three steps” you’ll find dozens of hits that regurgitate this falsehood. This is largely down to Ed Schein, the noted “culture change guru” not doing his homework — as Cummings et al describe in their paper: “Schein’s referencing of Lewin’s work in this regard is unusually lax. A footnote to an article by Schein (1996) on Lewin and CATS explains that: “I have deliberately avoided giving specific references to Lewin’s work because it is his basic philosophy and concepts that have influenced me, and these run through all of his work as well as the work of so many others who have founded the field of group dynamics and organization development. (Schein, 1996: 27)” - see p3 of 28 of the Cummings et al paper (marked p35 as the article begins on p32 of the original article in the Tavistock Institute Human Relations Journal 2016, Vol. 69(1).

Ibid — End of Change (preface page xii).

Note that these “shapes” are meant to be experienced viscerally. What’s it like to try moving a pyramid? Or flipping a large cube from one face to another? How about rolling a cylinder — and then steering it orthogonally to the rolling direction? What about a sphere?

Ibid — End of Change (preface pages xiv - xv).

Ibid — End of Change (preface pages xiv - xv).

Ibid — End of Change (preface pages xiv - xv).

Ibid — End of Change (preface pages xiv - xv).