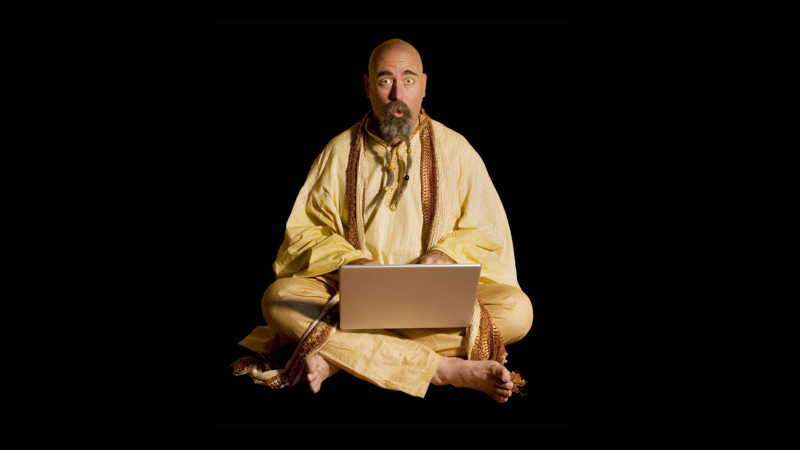

Gurus, gugus and rugus

When you bring in an external expert, make sure they don’t expropriate your sense making

“We use the word ‘guru’ only because ‘charlatan’ is too long to fit into a headline.” – Peter Drucker 1

In an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world, organisational success and survival depend on the ability to continuously sense and respond in appropriate ways to new opportunities and new threats.

This requires a future-fit culture of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness where sense making, decision making & action taking are tightly coupled, rapidly and repeatedly iterated, deeply embedded, and widely distributed throughout the organisation.

We’ve known this in theory for 30+ years. 2

But in practice, not much has changed.

Not because we don’t know what to do, but because of what gets in the way: deeply embedded habits of perception, thought and action based on a 100+ year legacy of doing things in ways that stifle, smother, and strangle innovation, agility and adaptiveness.

Central to this legacy are habitual assumptions about sense making and decision making – where they should happen, who should be involved, when, to what degree, and in what ways.

One of the most deeply embedded of these assumptions that blocks innovation, agility and adaptiveness is ‘decision makers’ = ‘senior executives’.

These terms have been used interchangeably for so long, it's still widely assumed that there are decision rights, and that the folks in big hats own them. 3

Sense making also faces a significant barrier, in that it’s often overlooked entirely or lumped in with decision making.

This conflation gave rise to the myth of the all-seeing, all-knowing visionary leader, blessed with unfailing wisdom and crystal clear foresight.

In reality, it takes multiple perspectives to make enough sense of a volatile, complex and increasingly messy world that effective action can be taken.

And, with ever-increasing uncertainty and unpredictability, senior executives can no longer outsource their uncertainty to management consulting firms or external ‘gurus’. 4

But there’s another, more subtle, and more insidious risk in relying on external experts, viewed here through three lenses:

Lens #1 - System Dynamics

System dynamics (SD) is one of several approaches in the field of systems thinking. 5

SD practitioners often refer to various systems archetypes – commonly occurring patterns of systemic behaviour with characteristic, well understood, underlying dynamics.

Examples include Fixes that Backfire, Success to the Successful, and of particular interest here, Shifting the Burden to the Intervenor. 6

Shifting the Burden to the Intervenor occurs when an expert intervenes in an organisation, but instead of increasing the organisation’s capacity for sense making, decision making & action taking, the intervenor takes on the burden themselves.

In some cases, the intervenor actually takes actions that people in the organisation ought to be taking themselves.

This is standard operating practice for big consulting firms - whose finders, minders, grinders business model is fundamentally dependent on shipping large numbers of junior consultant ‘grinders’ into client organisations to do the heavy lifting. 7

Shifting the Burden to the Intervenor also occurs when people in the organisation take the actions themselves but rely too much on an external expert for the sense making - and therefore fail to develop their own sense making muscles.

Lens #2 - Social Interaction

The Karpman Drama Triangle is a social model of human interaction devised by Stephen Karpman in 1968, and widely used in family and relationship therapy. 8

Often used in conflicted or drama-intense relationship situations, the triangle describes three roles people play out: persecutor, victim, and rescuer.

One of the major dysfunctions therapists seek to tackle is where the relationship between the rescuer and victim has become codependent – the former perpetuating the latter’s victimhood, whilst the latter simultaneously avoids addressing the root causes of their seeming victimhood by relying on the former to repeatedly rescue them. 9

Therapists have to pay careful attention not to inadvertently take on the role of rescuer and thereby perpetuate the problem dynamic.

Lens #3 - Marketing & Sales

Marketing and sales both seek to influence or dominate the sense making of target customers so the latter are more likely to buy.

About 30 years ago I participated in a sales skills development programme based on research showing that certain types of questions help create the impression that a salesperson is highly knowledgeable about the customer’s problems.

When a salesperson deploys these types of question effectively, it encourages customers to trust, and defer to, the salesperson’s sense making. 10

Obviously, the more a salesperson’s arguments make sense to customers, the more likely they’ll buy.

Whichever lens you use, when external experts expropriate sense making from people within an organisation, the latter fail to develop not only their sense making muscles but also their capacity for iterating and improving the integration of sense making, decision making & action taking throughout the organisation. 11

To be clear, I’m not saying organisations should never bring in external experts.

There are bound to be times when experts can add value to a client organisation. But it’s vitally important that imported sense making be used to improve, not impede, the capacity for sense making, decision making and action taking inside the organisation.

The expropriation of client organisation sense making can be a subtle, slippery, highly seductive slope for experts who’ve built careers based on acquiring specialist knowledge, insight, and experience to help others.

When your sense making abilities form a big part of your sense of self in the world, it can be tempting to have clients and organisations depend on you.

It makes you feel important.

It makes you feel needed.

And it can do wonders for your cash flow…

Gurus, gugus and rugus

As Peter Drucker famously observed, the term guru is loosely used for anyone who can make - or claims they can make - a significant contribution to sense making.

But this is not how a guru is traditionally understood in India, as explained here in the 2,000 year old Advayataraka Upanishad: 12

“The syllable Gu indicates darkness, the syllable Ru means its dispeller.

Because of the quality of dispelling darkness, the Guru is thus termed.”

So, a guru is actually someone who helps you make the shift from darkness into light – specifically, and importantly, from your darkness into your light.

A genuine guru does not expropriate your sense making by doing it for you, they help you do better sense making for yourself.

When an external expert doesn't help you do better sense making but instead does the sense making for you, they don’t take you from your darkness into your light, they take you from your darkness into their darkness.

So, based on the etymology explained in the Advayataraka Upanishad, they're not really a guru but a gugu.

But even worse than the gugu is the rugu - the expert who takes you away from the emerging light of your own sense making and into the darkness of their model, framework, or consulting methodology.

Then they monetise you.

So next time you consider engaging an external expert to help with sense making, first check whether they’re a guru, a gugu or a rugu.

Caveat emptor.

"Peter Drucker, the man who changed the world", Business Review Weekly 15 September 1997 p49.

For more detail on this download my 22-page report on the Five Fatal Habits that have consistently prevented organisations from creating future-fit culture of innovation, agility and adaptiveness for more than 30 Years.

See my earlier post Senior Executives Must Give Up Their Decision Rights.

Find out more about the weird and wacky predictability purveyors that pioneered the pathways trodden by today’s big consulting firms here.

Systems thinking is a wide field that encompasses many theories, approaches, and methods. It’s rife with examples of individuals proselytising a single approach as the whole field - a source for perennial, and often heated, debates on LinkedIn. Wikipedia provides a basic introduction to System Dynamics.

Wikipedia has a useful page introducing some of the common archetypes.

There’s an overview of this phenomenon on page 14 of my 22-page report on the Five Fatal Habits [Ibid]

Wikipedia has an introduction to the Karpman Drama Triangle.

This codependency is central to the long-term lock-in that partners in big consulting firms seek to establish with senior executive clients - described on p15-16 of my 22-page report on the Five Fatal Habits [Ibid]

Huthwaite’s SPIN Selling courses are still going strong after 40 years.

A future-fit culture of innovation, agility and adaptiveness is one where sense making, decision making & action taking become ever more tightly coupled, rapidly and repeatedly iterated, deeply embedded and widely distributed throughout the organisation.

The Advayataraka Upanishad dates from 100-300 BCE. The the term ‘guru’ is explained in verse 16.