Growth mindset - crucial but insufficient

Future-fit organisations thrive on extended intelligence by cultivating 2D3D mindsets

“We have lots of sayings that stress the importance of risk and the power of persistence, such as “Nothing ventured, nothing gained” and “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” or “Rome wasn’t built in a day.”

What is truly amazing is that people with fixed mindsets would not agree. For them, it’s “Nothing ventured, nothing lost.” “If at first you don’t succeed, you probably don’t have the ability.” “If Rome wasn’t built in a day, maybe it wasn’t meant to be.”” — Carol Dweck 1

Carol Dweck is a Stanford University Professor of Psychology known for her work on implicit theories of human intelligence, popularised in her 2006 book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. 2

Her model distinguishes between fixed and growth mindsets:

“In a fixed mindset, students believe their basic abilities, their intelligence, their talents, are just fixed traits. They have a certain amount and that’s that, and then their goal becomes to look smart all the time and never look dumb.

In a growth mindset students understand that their talents and abilities can be developed through effort, good teaching and persistence. They don’t necessarily think everyone’s the same or anyone can be Einstein, but they believe everyone can get smarter if they work at it”. 3

The Growth Mindset concept has gained huge traction in Dweck’s original research field of education, and more broadly — including in the organisational domain.

Dweck’s book has sold over a million copies. 4

Google claims growth mindset is the number one trait they look for in new hires. 5

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella cites growth mindset and Dweck’s book as being central to the cultural transformation that’s underpinned Microsoft’s 800% increase in market value since he took over in 2014. 6

Despite this success, growth mindset has attracted significant criticism from other psychologists, academics, and researchers.

The bulk of this criticism appears to centre on Dweck’s claims that a growth mindset increases an individual’s “intelligence”.

In her book, she clearly anticipates some of this pushback and seeks to counter it by invoking Alfred Binet, inventor of the first practical IQ test:

“Here is a quote from one of his (Binet’s) major books, Modern Ideas About Children, in which he summarizes his work with hundreds of children with learning difficulties: A few modern philosophers . . . assert that an individual’s intelligence is a fixed quantity, a quantity which cannot be increased. We must protest and react against this brutal pessimism. . . . With practice, training, and above all, method, we manage to increase our attention, our memory, our judgment and literally to become more intelligent than we were before.” 7

The controversy over whether intelligence is fixed and locked down, or malleable and can grow, is crisply summarised in a paper from the Centre for Educational Neuroscience at University College London (UCL), titled “Intelligence is Fixed”. 8

The paper cites a range of research related to and including Dweck’s, concluding:

“Together, these studies neatly show that while there is something about intelligence that is fixed, how intelligence is revealed depends strongly on the environment; that is, how we view our abilities, as well as the culture, the home and the teachers that we’re exposed to.

So, if we’re talking about intelligence as a theoretical underlying potential, then this is a neuro-hit. But if we’re thinking about whether children’s ability to perform in the classroom is fixed, it’s a glorious neuro-miss! Indeed, much cutting edge research in educational neuroscience is currently examining ways that children’s cognitive abilities may be improved through techniques as diverse as mindfulness training, working memory training, learning a musical instrument, increasing aerobic fitness, and learning a second language.”

In other words, UCL concludes that although an individual’s theoretical potential intelligence does seem to be fixed, the way we view our intelligence has a significant influence on our individual ability to apply it to performance.

Someone who has shed useful light on this crucial distinction is John Vervaeke, Professor of Cognitive Science at the University of Toronto, pointing out that Dweck “talks about two different ways in which you can set your mind towards your traits.” 9

The two ways Dweck says you can set your mind towards your intelligence are either a) that it’s a fixed trait or b) that it’s a malleable trait.

Vervaeke clarifies that mindset is more than just belief, saying “it’s the way in which you identify with, and feel you are embodying the trait”. 10

He continues:

“In the fixed view, you think intelligence is fixed at birth or early on. And then once it's locked in, there’s not much you can do with it. So, for example, my height is a fixed trait. There’s not a lot I can do to modify it. It’s a fixed trait. My weight is a much more malleable trait. I can change it — it’s quite variable. So you may think that intelligence is more like your height. You got this number assigned and that’s it. Or intelligence is malleable. It can develop and change.

Now notice your behaviour is going to be different if you think intelligence is fixed. If you think intelligence is fixed, your attitude towards error is that error will reveal that you have a defect in a non-changeable trait. It will permanently disclose that you are not smart.

So a fixed mindset tends to turn error into permanent revelation. If I make mistakes, that will show that I have low intelligence. And once everybody knows that, including myself, there’s nothing I can do about it. And then I’m doomed to being a stupid person.

If you have the malleable view of intelligence, error doesn’t do that for you. Error points towards the skills I’m using. I need better skills or I need to put in more effort — because if it’s malleable, I can do things to change it.” 11

Dweck’s research shows that people who adopt a fixed mindset often lie when asked to report their performance to others:

“After some hard problems, we asked the (fixed mindset) students to write a letter to someone in another school describing their experience in our study. When we read their letters, we were shocked: Almost 40 percent of them had lied about their scores — always in the upward direction. The fixed mindset had made a flaw intolerable.” 12

Hence Dweck’s observation that “when people adopt fixed mindsets their goal becomes to look smart all the time and never look dumb”.

What this means is growth mindsets are crucial to the experimentation, learning, and error correction through iterative sense making, decision making, and action taking at the heart of future-fit cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness.

But on their own, growth mindsets are not enough.

Why’s that?

In individualistic cultures, whether national, societal, or organisational, individuals with growth mindsets can all too readily focus on ‘getting smarter’ by themselves.

This tendency is further reinforced when individuals are rewarded, formally and informally, for being — or appearing to be — smarter than their colleagues.

However, innovation, agility, and adaptiveness only flourish when people go beyond this individualistic orientation and cultivate 2D3D mindsets instead. 13

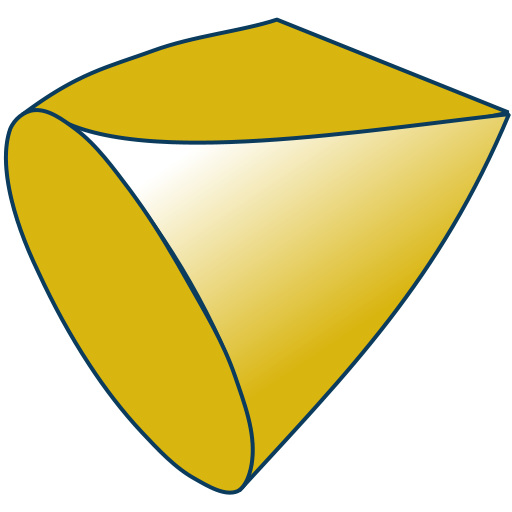

A 2D3D mindset recognises that none of us ever sees the whole of any situation and that what we each have, in effect, is a 2D perspective on a 3D reality that none of us can ever hope to see in its entirety.

It recognises that we can learn to see more — both by adopting growth mindsets ourselves and by being actively curious about the different 2D perspectives of others.

This orientation will continuously expand our awareness and understanding, even though we’ll still never be able to see the whole picture on our own.

The inability to see the whole isn’t a personal failing, it’s just a natural and inevitable part of being human.

But what is a personal failing is when we fall into the trap of believing that what we see is the whole picture — and that anyone who sees things differently is therefore self-evidently mistaken, misinformed, or misguided.

That attitude — especially in influential individuals— is a fundamental show-stopper for organisational innovation, agility, and adaptiveness.

Individuals with 2D3D mindsets actively seek out, respect, and collaborate with others because they not only recognise we can get smarter individually by cultivating growth mindsets — but more importantly we can get smarter collectively by cultivating 2D3D mindsets.

Organisations that actively cultivate widespread adoption of 2D3D mindsets unblock the capacity of their people to continuously co-create new value together, unlocking extended intelligence that’s far greater than the sum of individual intelligences. 14

That’s how they create future-fit cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness where sense making, decision making, and action taking are widely distributed, deeply embedded, and actively alive throughout the organisation.

And that’s how they develop the ability to flourish in an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world.

Question for reflection

Are the attitudes and behaviours of the people in your organisation more representative of fixed mindsets, growth mindsets, or 2D3D mindsets?

Do people get rewarded more for being individual stars, or for their contribution to co-creating new value together with others?

What does your personal stance lean toward — fixed mindset, growth mindset, or 2D3D mindset?

From Dweck’s book Mindset - Changing the way you think to fulfil your potential (p18). Revised edition published in 2017 by Robinson (Constable & Robinson Ltd.) ISBN: 978-1-47213-996-2

Unless otherwise stated, content cited in this post is from the 2017 version of Mindset with revised subtitle (Ibid).

From One Dublin interview with Dweck 19 June 2012.

Mindset is ranked #5 on the 100 best-selling mindset books on BookAuthority.org

The #1 Trait Google looks for in ‘ideal’ job candidates CNBC (10 May 2018).

In this previous post I describe how Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella credits Dweck’s book Mindset with inspiring him to create a learning culture at Microsoft.

Mindset p13-14 (Ibid).

John Vervaeke Awakening from the Meaning Crisis Episode 42 at 44:44. Direct link to that section here.

Ibid (Vervake Episode 42) at 45:04.

Ibid (Vervake Episode 42) at 45:20.

Ibid (Dweck, Mindset) p113.

For more on 2D3D mindsets, see this previous article.

Extended intelligence is one of four dimensions of 4E Cognitive Science. For more on this topic see this earlier article.