Debate and Discussion - or Dialogue?

Do the conversations in your organisation cultivate the capacity to co-create new value? Or do they undermine it by promoting narrative warfare...?

“We see nothing truly till we understand it.” — John Constable 1

People experience their organisation’s culture as the way we do things around here.

Focusing on culture as lived experience is key to identifying pragmatic, low risk, high leverage ways to create the cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness organisations need if they’re to thrive in an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world. 2

One of the first things to understand about organisational culture is that no two people experience the culture in exactly the same way.

In other words, there’s no such thing as a single, unified, uncontested culture.

Even for a given individual, the lived experience of the culture is dynamically changing, based on their constantly shifting experience of who “we” are, and what “around here” means.

Sometimes, “we” is the self plus one other person.

Sometimes, “we” includes several of “us”, such as fellow team members, people in the same department or function, the same physical location, the ones who happen to be in the current meeting, Teams or Zoom call, breakout room, etc.

Sometimes, “we” includes the whole organisation.

In other words, “we” and “around here” are dynamic, fluid, and ever-changing.

In this ever-changing “around here”, four things “we” do are of central importance:

How and how well we do sense making,

How and how well we do decision making,

How and how well we do action taking,

How and how well we join up sense making, decision making, and action taking.

In an increasingly uncertain and unpredictable world, sense making, decision making, and action taking must become ever more tightly coupled, rapidly and repeatedly iterated, deeply embedded, and widely distributed throughout the organisation.

In a nutshell, that is the way we do things in a future-fit culture…

Organisations have traditionally focused a lot of attention on decision making and action taking, but not so much on sense making.

That’s unfortunate, because good sense making is the key to everything else.

It’s also unfortunate that the vital importance of sense making is most acutely understood by those who seek to control it for their own advantage at the expense of others.

That’s why oligarchs whisper in the ears of the autocrats in dictatorships.

And it’s why think tanks and lobbyists schmooze political parties in democracies.

If you frame life as a game of getting people to buy what you’re selling, and reject what someone else is selling — be that a political narrative, organisational ideology, or a paid-for product or service — then sense making becomes a game of narrative warfare, a win and lose battle where, as Abba sang, the winner takes it all. 3

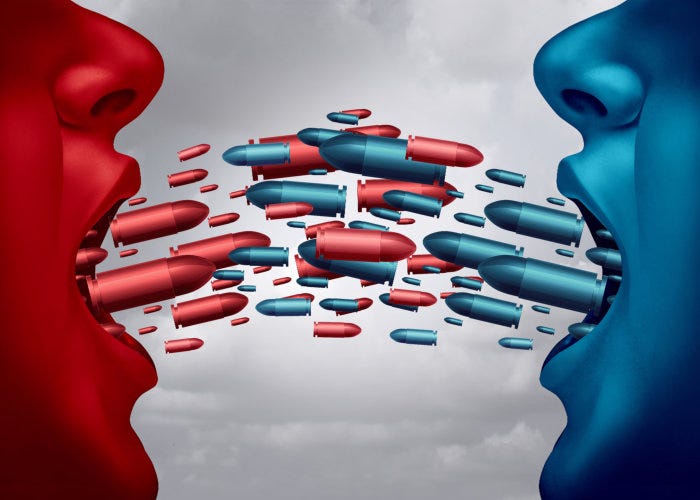

The two conversational styles that dominate the narrative warfare game are debate and discussion.

Debate

The word debate entered English in the late 14th century, when it originally meant “to combat, fight, make war” as well as its current sense of “to quarrel, to dispute”.

Debate is derived from the old 13th century French debatre (in modern French débattre), meaning “to beat down completely” from de- “down, completely” + batre “to beat”, ultimately from the Latin battuere “beat” — from which we also get the English verb “to batter”. 4

Think of the kind of conversation most often associated with politicians from opposing parties — aiming to win the narrative war by beating down their opponents.

Given that goal, rhetorical tricks and traps are frequently employed to undermine others’ credibility.

Discussion

The word discuss also entered English in the 14th century, stemming from the Latin discutere meaning “to dash to pieces, agitate, strike or shake apart” from dis- “apart” + quatere “to shake”, and from which we also get the English verb to quash and the French verb casser “to break, smash, destroy”. 5

Both debate and discussion frame conversation as a win or lose battle between verbal combatants engaged in narrative warfare — the only difference is that whilst debate focuses on beating down the opponent, the focus of discussion is on smashing their argument to pieces.

The problem with all this is that none of us ever sees the whole picture in any situation.

All each of us ever has is a narrow, biased, one-sided “2D” take on a “3D” reality that none of us ever sees, or ever can see, in its entirety.

So the best that we can achieve through narrative warfare is that our limited, biased, and one-sided, partial, and impoverished 2D perspective displaces another equally limited, biased, and one-sided partial 2D perspective.

One party “wins”, the other party “loses” and everyone, including the non-combatants, miss out on the real prize, which is the vastly greater value created by combining the best aspects of multiple individuals perspectives into something greater — far greater — than the sum of the parts.

Director of The Consilience Project Daniel Schmachtenberger describes how we get drawn into narrative warfare when we become trapped in our narrow perspectives: 6

“One of the sources of bias is identifying with what I believe, because I'm identifying with part of an in-group that believes that thing, or because I am special, or smart, or right, or whatever for believing that thing. So the impulse to be right means that I won't seek to understand other perspectives. If I'm going to seek to understand the truth value in other perspectives — to earnestly try and get what they are seeing what where they're coming from, I have to stop seeing it the way that I'm seeing it for a little while. I also have to completely suspend debate and narrative warfare and the impulse to be right and all of that. And so there is a deeper human connection that's involved.” 7

Dialogue

The question to ask ourselves is what is my attitude and intention when I engage in conversation with others?

Do I engage to win through debate and discussion, by beating others down or smashing their arguments to pieces, or do I engage in earnest dialogue?

The word dialogue is formed from two Greek roots dia “across, between” and logos meaning “speech, word, reason, meaning”. 8

In creating future-fit cultures of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness a useful way of understanding dialogue is the emergence of richer shared meaning (logos) through the combined sense making between (dia-) multiple people engaged in earnest truth-seeking, as opposed to narrative warfare.

Daniel Schmachtenberger offers further valuable insight:

“For me to really try and get where you’re coming from on a topic I have to really take your perspective. Well, what is it in me that’s taking your perspective — because it’s not my perspective? It’s actually having to drop the way I see things to really try and see it the way you see things — to make sense of it. So that means there’s a capacity in me that can witness my perspective, that can also witness your perspective, but it is deeper than the current perspective I have. And we all know we can change our beliefs and there’s still something that is us. So there is a us-ness that is deeper than the belief system. To be able to really try to make sense of someone else, I actually have to move into that level of self that is deeper than belief systems.” 9

So how do you “move into that level of self that is deeper than belief systems”?

This is the shift that happens when conversation participants adopt, and operate and interact from a 2D3D mindset.

Someone operating from a 2D3D mindset actively engages with others from the embodied awareness that all each of us ever has is a biased and incomplete 2D perspective on a 3D reality none of us can ever see in its entirety.

This recognition, when it genuinely hits home in a visceral way, unlocks our innate human curiosity about what others see that we don’t yet see. 10

We then stop indulging in the pointless point-scoring of win-lose narrative warfare through debate and discussion.

That's why a deep commitment to the practise of dialogue is central to creating a future-fit culture of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness.

Dialogue is the only one of the three forms of conversation that creates conditions conducive to appreciation of nuance, enrichment of current perspectives, and clarification of misinterpretations.

It's the only one that supports genuine collaborative sense making.

And it's the only one that encourages widespread adoption of the 2D3D mindset at the heart of a future fit culture of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness.

Questions for reflection

Is dialogue the default culture of conversation in your organisation — or do people automatically default to debate and discussion?

Is your personal default — in practice, not theory — more towards dialogue or more towards debate and discussion?

How much time and effort do you spend advocating your 2D perspective on situations as opposed to being genuinely curious about, and actively inquiring into, the 2D perspectives of others? Do you need to achieve a better balance?

John Constable (1776 – 1837) was mainly known for his landscape paintings of the area around his Suffolk home. The quote is from his third lecture on The History of Landscape Painting at the Royal Institution on 9th June 1836.

For more on the vital importance of understanding culture as a lived, embodied experience, see the previous article The secret everyone already knows.

Released as the first single from the group's seventh studio album, Super Trouper (1980) the music video, watched more than 144,000,000 times, is here.

The Consilience Project, explores the key challenges and existential threats facing humanity, the underlying problems with current approaches for addressing them, and aims to improve the nature of conversations to overcome these problems.

Daniel Schmachtenberger in his War on Sense Making I conversation with Rebel Wisdom co-founder David Fuller at 1:35:17 to 1:36:06 in the recording.

Daniel Schmachtenberger War on Sense Making I conversation at 1:36:17 to 1:37:01 in the recording.

See this previous article on 2D3D mindsets — Unlocking the innovative mindset.