Death by mistaken identity

You may know what you're selling - but what are your customers actually buying?

“We know what we are, but know not what we may be.” - William Shakespeare 1

Do you know what business you’re really in?

Ever since the New England area was settled by migrants, ice from its ponds was a valuable commodity for cooling drinks and preserving food.

For generations, ice harvesting was little more than a cottage industry, where individual families, or their servants, would cut ice by hand in winter and store it in underground cellars for use in the summer.

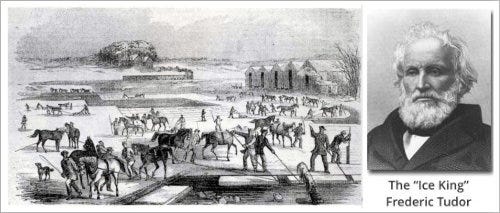

Then in the early 19th century a Boston entrepreneur called Frederic Tudor saw the commercial potential for New England ice.

Rather than going to study at Harvard, he instead set up The Tudor Ice Company, and a new industry was born: the New England ice cutters.

Tudor's business strategy was one that would be familiar to many contemporary entrepreneurs: achieve sustained profitable growth by exploiting technology - in his case applying it to the cutting, storage, and shipping of ice.

He hired inventor Nathaniel Wyeth and between them their steam saws, loading, and shipping innovations boosted efficiency, increased productivity and drove year on year growth for decades.

He used the cost advantages to undercut competing suppliers, including giving away free ice to bartenders, and then charging once customers were hooked on cold drinks. 2

In 1806, Tudor shipped a cargo of ice to Martinique in the West Indies.

Although he lost money on the venture it opened a new market that would eventually become highly profitable.

Twenty years later, The Tudor Ice Company was shipping 12,000 tons of ice a year and Frederic Tudor had become known as “the Ice King”.

In 1833 he exported 200 tons of ice on a 180 day journey to India in a ship employing state-of-the-art Tudor/Wyeth sawdust-based thermal insulation.

Half the shipment survived, and even though it sold at a net loss, the Ice King's empire was expanding.

Tudor constructed above-ground ice storage facilities incorporating Tudor/Wyeth thermal insulation.

One of these still stands in Chennai, India, as a local monument to Tudor's ingenuity and entrepreneurship.

In 1857, at the age of 74, Tudor still saw a bright future and told the Boston Board of Trade that the ice harvesting industry was “yet in its infancy”.

He saw no reason why the strategy of the previous fifty years should not continue, as innovation in cutting, storage and shipping technologies showed no sign of slowing.

But even as he spoke, the first ice-making plants were starting up in the United States.

Blinded by past success, The Tudor Ice Company failed to see the threat that this new technology posed to their business.

The number of machine-made ice plants grew exponentially to several thousand by 1920, by which time the New England ice cutting industry had melted away…

On one level, the story of the rise and fall of the New England ice cutters can be seen as just another example of how disruptive innovation destroys well established market leading organisations, and even industries.

A new technology comes along that changes the basis of competition but gets dismissed, ignored, or overlooked by market leading incumbents heavily invested in legacy technologies key to their past successes.

And whilst that's a valid perspective, it's worth digging deeper into why the prolifically innovative Tudor failed to exploit machine made ice.

The Tudor Ice Company had great potential as pioneering adopters of refrigeration technology:

They had an established international market for ice and a very strong existing customer base.

They had the international transport and logistics network needed to service and extend that market.

They could have phased in machine-made ice gradually as and where harvested ice became less competitive.

The deeper reason that the Tudor Ice Company failed was that they didn’t know what business they were really in.

They were caught in an organisational Seeing-Being Trap 3 due to their awareness of being ice cutters.

Had they escaped this limitation, and instead of ice harvesters been aware of themselves as ice producers, machine made ice would have been seen as a relevant opportunity.

In a case of death by mistaken identity, being in the business of harvesting ice meant they literally couldn’t see the relevance of other ways of producing ice. 4

And so they went out of business when machine made ice became a more cost effective way of providing customers with what they actually wanted - ice, not harvested ice per se.

There's some old marketing wisdom that says when customers buy 1/4 inch drill bits, they don't actually want 1/4 inch drills, what they actually want are 1/4 inch holes.

But if you're a drill bit producer, especially a market leading one, it's easy to forget that in your customers’ eyes, you’re in the hole provision business.

Those hard won, heavily invested legacy skills in metallurgy, heat treatment, volume manufacturing, etc. make other potential hole-producing technologies such as punches, lasers, high-pressure water jets etc. seem irrelevant - even though all are potential alternative ways of giving customers what they actually want.

With Frederic Tudor, the question “what business are you really in?” doesn't end with the realisation that customers want ice as opposed to harvested ice.

What customers really wanted wasn’t ice per se but a way to cool drinks and food.

That’s why, as we know looking back from our vantage point a century later, home refrigeration is a highly relevant technology, with domestic fridges eventually replacing ice production, shipping, and the use of ‘ice boxes’.

So it seems that customers didn’t even want ice.

What they actually wanted was cold.

Or did they?

What some customers actually wanted was food preservation.

That’s why today we commonly buy liquid foodstuffs including long-life UHT milk, soups, sauces, soya, oat, and nut based drinks in aseptic packaging - a technology that provides extended shelf life to products that only require refrigeration once they’ve been opened. 5

And no doubt further innovations will disrupt today’s aseptic packaging manufacturers if they don’t really understand the ever-evolving nature of what their customers are actually buying.

The history of human enterprise is full of examples of organisations that needed to rethink what business they were actually in.

Whilst some respond to that call, many fail to heed it or even hear it at all.

A few of my other favourite examples are:

Black & Decker - who rejected Ron Hickman's collapsible workbench idea that became the 'Workmate'. A big hit with users for holding work steady, as a 'power tool company' B&D couldn't see its relevance as it had no motor. They only acquired the rights after Hickman launched the product himself.

Kodak - world leaders in mass-market photography for over a century, were far too slow making the shift to the very digital technologies that allowed people to actually achieve their motto “share moments, share life”. 6

Xerox - who, despite investing hugely in technology for the paperless office, and inventing many of the technologies used in the personal computer, smartphones and tablets, failed to commercialise them. 7

Procter & Gamble - who threatened to fire the internal champion of the “silly disposable diaper project” that became market leading Pampers. P&G were a soap company and a disposable diaper not only didn’t sell soap, it might even reduce sales of soap for washing cloth diapers…

All the above businesses were pretty sure they knew what they were selling, but didn’t really understand what their customers were actually buying.

What are your customers actually buying?

What business are you in..?

Are you sure?

Hamlet. Act IV, Scene V

The most popular ice came from Wenham Lake, Essex County, Massachusetts. In 1864, the Norwegian lake Oppegård was renamed Wenham, and much of the “Wenham Lake” ice sold in Britain was actually from this Norwegian impostor.

Seeing-Being Traps can affect individuals, teams, groups, departments, and entire organisations. This 7 minute video describes how they impede progress.

It may sound a subtle distinction but “We are ice harvesters” as opposed to “We are ice producers” blinded Tudor to ice production that didn’t specifically involve harvesting.

Like many corporate mottos, Kodak’s was more ad agency PR slogan.

To be fair, Xerox did invent laser printers - by taking the back end of a Xerox 7000 photocopier and replacing the front end imaging mechanism with a scanning laser - an adaptive, rather than disruptive, innovation.