The seven channels of culture

Understanding the clues, cues, signs, and signals forming and informing ‘the way we do things round here’.

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. - Clarke’s Third Law

‘The secret everyone already knows’ highlighted how efforts to influence organisational culture go awry when they rely on academic definitions of culture instead of the actual embodied experience of it in real life. 1

Focusing on this embodied experience is essential if we want a pragmatic, low risk, high leverage way to create a future-fit culture of innovation, agility, and adaptiveness.

One of the first things to recognise is that no two people experience an organisation’s culture in exactly the same way.

Therefore, there’s no such thing as a single, unified, uncontested culture. 2

However, people who work together usually have some common and shared experiences of ‘the way we do things round here’.

If they didn’t, they wouldn’t have any meaningful “we” or “round here”.

However, even a single individual’s experience of ‘the culture’ varies, based on their dynamically changing embodied experience of who “we” are, and where “round here” begins and ends.

To get to grips with this seemingly unfathomable dynamic complexity we must avoid the trap of tackling it purely propositionally and instead work with the recognition that culture is inherently an embodied experience. 3

Think about a workplace. Who are “we” and where is “round here”?

Sometimes, “we” is the self plus one other person.

Sometimes, “we” includes several of “us”, e.g. fellow team members, people in the same department or function, the same physical location, the ones who happen to be in the current meeting, Zoom call, breakout room, etc.

Sometimes, “we” means the whole organisation - e.g. when talking about it to someone who doesn’t work there.

As an example, two people may jointly work on an item for the BBC’s flagship ‘Six O'clock News’ programme (“we two”).

Then they will work with the rest of the team to refine, schedule, produce and deliver the item (“we, the 6 News team”).

6 News is just one of many BBC news channels, which usually see each other as competitors.

However, when there’s a story bigger than just one channel — such as 9/11, the funeral of a senior member of the Royal Family, or Covid-19 (yes the unifying news stories tend to be negative) the different BBC news channels tend to cooperate (“we, the BBC”).

When you see how fluidly and dynamically both “we” and “round here” change, you start to get a feel for the huge dynamic complexity, and the contested nature, of organisational culture.

All this complexity can be scary.

That’s why people so often either avoid tackling culture at all, or fall for seductive oversimplifications that dumb down the complexity - as described here by H. L. Mencken:

“Explanations exist; they have existed for all time; there is always a well-known solution to every human problem - neat, plausible, and wrong”. 4

So, how to move forward in the face of such seemingly intractable complexity?

Well, when it's difficult to see your way forward, a step back is often a step in the right direction - towards a better way of seeing.

Here’s where I found an early career experience a helpful pointer to how it might be possible to cut through the seeming complexity of culture.

Back in the early 1980’s I was a studio and broadcast transmission chain engineer with the BBC.

I saw that if you look at the FM radio band (88-108MHz) using an oscilloscope — a device for displaying signal strength vs time — the screen is just a squiggly, squirming chaotic mess, with no way to pick out anything discernible.

However, feed the same FM band into a spectrum analyser — a device for displaying signal strength vs frequency — and hey presto, you’re presented with a simple, neatly spaced sequence of vertical lines, each centred on a single radio channel with a height proportional to signal strength. 5

It turns out that a similar approach works with organisational culture.

As we saw in The secret everyone already knows, we form our embodied experience of culture based on two main factors: 1) Whom we perceive really matters in enabling / impeding our access to what we’re looking for from our work; and 2) What we perceive really matters to who really matters. 6

What clues, cues, signs, and signals do people pick up to infer who and what really matters?

Insightful and pragmatically applicable answers to this question were discovered in the mid 1990’s by MIT Sloan School’s Ed Nevis, Helen Vassalo, and my former colleague Joan Lancourt - in a major research study into successful organisational transformations. 7

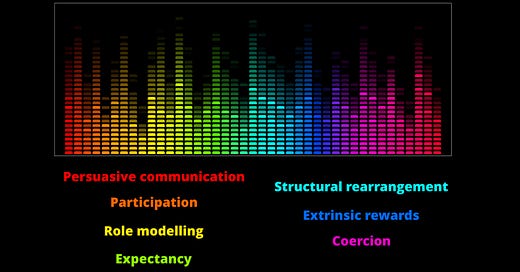

The study identified seven ‘signalling channels’ — the equivalent of radio stations — through which people pick up the clues, cues, signs, and signals they use to suss out ‘the way we do things round here’.

The seven channels identified by Nevis, Vassalo & Lancourt were:

Persuasive communication. This is where “a communicator attempts to introduce a change in the belief, attitude, or behaviour of others via messages that recipients receive with a degree of free choice”.

Participation. “Involvement in defining and shaping the future, allowing for the generation of good ideas and encouraging support and commitment for implementation”. 8

Role modelling. The “observation of social cues that people are often unaware of observing” in the attitudes and behaviours of influential individuals.

Expectancy. The most subtle of the seven channels, “Expectancy is often referred to as the inducement of self-fulfilling prophecies, in which expected behaviour becomes a reality”. 9

Structural Rearrangement. This is a traditional ‘go to’ lever that senior executives instinctively grab when attempting organisational change. It includes various forms of “altering work design, organisational structure, or core processes” such as restructuring, reorganisation, written rules, processes, procedures, policies, etc.

Extrinsic Rewards. Another traditional change lever, often pulled without much consideration of likely adverse side effects, “based on the assumption that the behaviour will not be maintained without extrinsic reinforcement”. 10

Coercion. Any practice “based on the assumption that people will comply because they see themselves as unable to leave the field in which the power is applied”.

Again, we can see how attempting to analyse the various and varying clues, cues, signs, and signals conveyed via these seven channels propositionally for each individual would result in massively overwhelming and indecipherable complexity.

Once again, the trick is to avoid this trap and instead apply how we actually experience culture — not as a set of propositions but as an embodied, lived experience.

So, look inside and ask yourself, “In my current or a previous work situation, what clues, cues, signs, and signals do / did I pick up through each of these seven channels”?

Having done that, next ask yourself “To what degree are / were the clues, cues, signs, and signals I pick / picked up aligned, coherent, and congruent as opposed to misaligned, incoherent, or at cross purposes”?

For example, did someone senior make speeches about the importance of teamwork (Channel 1), whilst extrinsic rewards (Channel 6) were doled out based on individual performance metrics?

When this happens, people feel the sensible way to behave is to stand out as the best individual team player…11

Or, did someone leading a major project or new business initiative (Channel 5) exhibit attitudes and behaviours (Channel 3) that violated supposedly sacrosanct organisational “core / shared values’’..

When this happens it sends the signal “You’ve really made it when you’re so valuable to the organisation you can get away with violating the values”. 12

An individual’s embodied experience of the culture is the net product of the clues, cues, signs, and signals they pick up through these seven channels.

If you explore what people in selected areas of the organisation pick up, you’ll notice patterns that guide you back to a small number of influential individuals.

It is these key influencers, not always in the most senior positions, whose mindsets, attitudes, and behaviours systemically dictate important aspects of the mindsets, attitudes and behaviours of everyone and everything else.

This makes key influencers the highest leverage place to change the system of mindsets that forms an informs people’s awareness of the way we do things round here – aka the culture. 13

Find out more about how to identify key influencers, the mindsets required to create a future-fit culture of innovation, agility and adaptiveness, likely barriers to implementation and how to overcome them in the eight short videos here (each <7 mins, total viewing time 45 mins).

That’s one reason (of many) why the toxic myth that an organisation’s culture is its ‘shared values’ is so damaging.

The difference between propositional knowing and embodied knowing is addressed in this previous article.

Since 1984, ITU channel spacings have been 100kHz or 200kHz. South of England FM channels graphic courtesy of Jim’s Aerials

Ibid.

Published in their 1996 book Intentional Revolutions.

Essentially this means the experience of participating adequately in sense making and decision making, as opposed to just action taking. Restricting “front line” workers to action taking was central to traditional top-down command and control management practice. The underlying orthodoxy that “bosses decide what gets done, workers do what they’re told” was enshrined in F. W. Taylor’s 1911 book The Principles of Scientific Management and has underpinned legacy management practice ever since.

Also known as the Pygmalion Effect

A useful resource on this is Alfie Kohn’s book ‘Punished by Rewards’ and his observation that “carrots and sticks are two sides of the same coin - and it’s a coin that doesn't buy you very much”…

If that doesn’t immediately seem crazy, then consider the behavioural implications…

Some people are seen as “more valuable than the values”.

To understand systemic leverage, check out Donella Meadows’ seminal paper “Leverage Points - Places to Intervene in a System”.